On April 2, 1926, the following article appeared in The Winnipeg Evening Tribune (p 3):

Noted Reader Lions’ Guest

Miss Elsie McLuhan Delights with Readings at Weekly Luncheon

Miss Elsie McLuhan, Winnipeg, known from coast to coast as a reader and impersonator, delighted members of the Lions’ club at luncheon in the Fort Garry Hotel Thursday afternoon, with a reading, entitled “Life.”

Introducing her subject, Miss McLuhan said that fear was one of the greatest handicaps of the human race. It ate into the very fibre of a man, blighted his hopes and ambitions, and held back his success, she said.

The allegory presented in a comprehensive manner by Miss McLuhan dealt with life personified as a master of some and slave to others. The characters were Life and two young girls who had yet to taste of life’s bitter cup.

The scenes were laid on a path running through a wood. On either side of the path stood the two girls, each with a crown on her head. One was fearful of Life, the other determined to exact from him everything she could.

Master or slave

The [latter]1 girl stated that if one were master of Life, life would be a beautiful and obedient slave. On the other hand, if Life became the master, he would show no mercy or pity for the fallen who were his slaves.

The [former] girl then asked why she wore her crown, and the other replied that when Life saw it, he would know that the wearer was his master.

Then Life appeared on the scene, first as an ogre, then, when he saw the crowns on the girls’ heads, as a bent man. He asked them what they wanted. They told him and he hurried to carry out their wishes.

Eventually the girl who was unafraid went her way with her crown still on her head and the other girl was forced to fight life alone. Life finally overcame her and slew her because she feared him and did his bidding. He accomplished this first by getting possession of her crown and then forcing her to fear him. Then he killed her.

It is easy to see why life on Gertrude Ave was so difficult for the McLuhans. Elsie was caught up in a life and death struggle and the battle she was waging turned on the mastery of fear — including, fatefully, fear of what she might be doing to her family, fear of what others might think of her, fear of going entirely her own way. If she did not overcome these fears, she felt, she would die (presumably in some figurative sense, but one she may well have thought worse than physical death).2 She was driven to be “the girl who was unafraid [and] went her [own] way with her crown still on her head”. In fact, there is a wonderful photo of the McLuhan family out for a drive around 1915:3

Elsie and Herb are in the front, Herb’s parents, James and Margaret, in the rear with Maurice.4 Elsie has a stupendous crown,5 twice the size of the men’s bowlers, and she is, naturally, the one at the wheel with the driving gloves.

The meaning of human existence turned on just how “determined” a person was “to exact from him [ie, Life] everything she could”. The gender opposition here is telling: “exact from him everything she could”. At 507 Gertrude Ave there were, of course, only men along with Elsie6 and Herbert’s initials were H.E.!

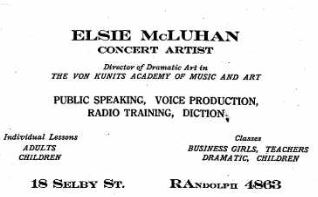

Elsie’s compulsion to prove herself aside from them, and if need be against them — a compulsion which found definitive expression in 1933 when she left Gertrude Ave and Winnipeg forever — an event to which she supplied a press release!7 — had long been intimated. When she first began to perform, around 1920, one of her repeated pieces was “Hunting an Apartment”8 and by 1926, as seen in the newspaper blurb above, she was styling herself as “Miss Elsie McLuhan”.9

A 1933 note written to her brother, Ernest Raymond Hall, records her in her first week in Toronto: “I was nearly crazy getting away [from Winnipeg and her family] (…) but I am determined to make this thing go”.10

McLuhan would have imbibed this attitude to life along with his mother’s milk and it must have been drummed deeper and deeper into him over the years through her incessant work on her readings and sketches — and through her equally incessant attempts to beat McLuhan’s father, Herbert, into wanting the sort of mastery she wanted. Marchand (163) characterizes McLuhan’s relation with her in a wonderful passage as follows:

When she died, McLuhan was grief-stricken. Elsie had been, at best, a difficult parent, spreading unhappiness about her like an aerosol that made it hard to breathe. Yet if McLuhan had inherited his tender conscience and firm morality from his father (…) he had inherited from his mother a spunkiness, an outrageous independence and indifference to what others thought, that set him apart and marked his approach to every project he ever pursued. He inherited something else as well: an irrepressible verbal aggressiveness. He was more like his mother than he was like anyone else on earth.

Marchand is right to note that McLuhan had also internalized an opposing assurance from his father for whom all was well, even the problems with Elsie, on some “higher plain”.11 For example, Gordon (27) records the following diary note from June 3, 1931:

I am of a critical and inquiring nature but the true Christian experience (…) is a fact that transcends analysis. Once filled with this miraculous spirit one may or may not give up one’s ideals and plans; but whichever happens, there is never a regret. There is absolutely nothing that can disturb the calm poise (…) that is the happy lot of the true Christian.

McLuhan’s life path was established through the solution he found to this struggle which raged in his mother and between his mother and father and, inevitably, in his own soul as well.12 Two central aspects of his solution may be seen in letters he wrote home from Cambridge when he was 23 and 24. A letter from December 6, 1934 to his family reports

Of late I have been wayfaring among the work of T.S. Eliot. He is easily the greatest modern poet, and just how great he is remains to be seen, because he has not produced his best yet. However the poems I am reading have the unmistakable character of greatness. They transform, and diffuse and recoalesce the commonest every day occurrences of 20th century city life till one begins to see double indeed — the extremely unthinkable character, the glory and the horror of the reality in life (yet, to all save the seer, behind life) is miraculously suggested. (Letters 41, emphasis added)13

For the purposes at hand, the key point in this passage is the denial that “the glory” of life is to be found on some “higher plain” somewhere “behind life”. Instead, if “the glory” were to be found anywhere at all, it must be here and now in “the commonest every day occurrences of 20th century city life”. And, although from some points of view this might seem to “transform and diffuse” those “occurrences” into something else, in fact it represents the reverse action of recalling them from what they are not14 to what they are15 — meaningful entities exactly in their particularity and without cosmetics and fantasies.16

In a later letter to his mother from September 5, 1935 he repeated against his father’s contentment with a “by-and-by” satisfaction that

My hunger for “truth” was sensuous in origin. I wanted a material satisfaction for the beauty that the mind can perceive. (Letters, 73, emphasis in the original)

This much he entirely shared with Elsie. But against Elsie’s Machiavellian drive, “to exact from [Life] everything she could” by becoming “master of Life”, McLuhan began his September 1935 letter by noting “the greatest fact about man, namely that he is a creature and an image, and not sufficient unto himself” (Letters, 72).

These points against both Herbert and Elsie are brought together in this same letter to Elsie through a quotation from Hopkins:

But good grows wild and wide.17

Has shades, is nowhere none;

But right must seek a side

And choose for master one. (Letters, 74)

The good is to be found, if it is to be found at all, not in some “higher plain”, but only in the “wild and wide” of the world as it is encountered in “every day occurrences”. This does not, however, precipitate a situation of “master or slave” where the only possibility of meaning lies in mastering life to make it “carry out [its master’s] wishes”. For in this case, where would the reputed “master” first of all find her strength and her rights? Was she to compose these, too, like Baron Münchhausen extricating himself from a mire, along with the horse he was riding, by pulling up on his own pigtail?

McLuhan knew early on that this was a delusional and hopeless idea. As he wrote to Elsie at this same time (January 18, 1935) concerning lectures he was attending of I.A. Richards:

Richards is a humanist who regards all experience as relative to certain conditions of life. There are no permanent, ultimate, qualities such as [the] Good, Love, Hope, etc., and yet he wishes to discover objective, ultimately, permanent standards of criticism (…) what a hope!… (Letters, 50)

Reality cannot be certified by one who will then apply that certification to herself (in order to be in a position to certify reality). And the same applies to any “permanent, ultimate, qualities”. All these must either be already the case just where we are — or not at all. Nihilism is simply the rigorous development of the ludicrous idea that humans, “sufficient unto [themselves]”, might construct reality in art or social life or anywhere else. And of the even more ludicrous idea of constructing their own reality.

The only answer, McLuhan could see, was that of “the glory and the horror of the reality in life” (cited above from Letters, 41). And this implied taking direction (in many senses) from the institution that had been “in life” for two thousand years, and therefore subject to its own glories and horrors, namely the church, for which the relation of “the glory and the horror of the reality in life” was a reflection or “uttering” of the fundamental relation in the Godhead itself — McLuhan’s “the meaning of meaning is relation”, “the medium is the message”. Hence his citation for Elsie from Hopkins:

But right must seek a side

And choose for master one.

Mastery is either in us to be exercised or outside us to be acknowledged. Every human action or perception “must seek a side” of this alternative before it unfolds. Humans are that peculiar type of animal that is ineluctably ex-posed to the a-priori time of this decision.

McLuhan had learned for himself, and was attempting to communicate to his mother, what Eliot would put in the first of the Four Quartets, ‘Burnt Norton’, later that same decade:

…echoes Inhabit the garden. Shall we follow?

Quick, said the bird, find them, find them,

Round the corner. Through the first gate,

Into our first world, shall we follow

The deception of the thrush? Into our first world.

(…)

Go, said the bird, for the leaves were full of children,

Hidden excitedly, containing laughter.

Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind

Cannot bear very much reality.

Time past and time future

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.

It was the “always present” time of this “first world”, where the question of mastery is deeply posed, that McLuhan would tirelessly attempt to explicate over the next half century. For this multiplication of time, of “time past and time future”, of “what might have been and what has been”, together with that “which is always present”, constitutes the strange environment of human beings — one that is just as little appreciated as water is by fish.

Hopkins, however, did not write ‘master’ in his poem, but ‘chieftain’: “And choose for chieftain one”. McLuhan’s slip, it may be imagined, went back to his mother’s unhappy quest to become the “master of Life.” McLuhan’s suggestion to her was that he, at least, would complicate and fundamentally revise such notions both of Life and of mastery.

- The Tribune article mistakenly has ‘former’ here. ↩

- McLuhan would later encounter just this same mania in Norman Mailer. It must have been somewhat amusing for him to find in this inveterate wild man what he knew so well from an elderly woman — his own mother. ↩

- The two photos of Elsie here have been posted to the Family Search site. ↩

- It is possible that this is Marshall, not Maurice, but this would date the photo to 1912. ↩

- Another photo of Elsie (from around 1910) shows her in another crown battle with her mother:

But here the driving gloves are worn not by Elsie but by her mother! Moreover, although Elsie was taller than her mother, here she is sitting and appears shorter. ↩

- For the five year period between Elsie’s father’s death in 1926 and her own death in 1931, Elsie’s mother, Margaret May Marshall Hall, lived with the McLuhans at 507 Gertrude. ↩

- The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, September 9, 1933 (Page 4): “Elsie McLuhan Leaving To Take Toronto Post — Elsie McLuhan, well-known local reader and impersonator, has accepted a position as director of Dramatic Art in the Von Kunits academy of Music and Art, Toronto. This academy is being opened by the widow of Dr. Von Kunits, former director of the Toronto symphony orchestra, as a memorial to his memory. Elsie McLuhan (…) will be leaving Winnipeg on Wednesday” (September 13, 1933).

↩

↩ - This skit was announced for shows in the Winnipeg Tribune for, eg, February 21, 1921 and later again for November 12 that year. ↩

- “Miss Elsie McLuhan Delights with Readings at Weekly Luncheon.” To contrast, in her earliest announcements, she announced herself as “Mrs H.E. McLuhan”! ↩

- Her note is online at Family Search. ↩

- As reported by Marchand (12) from McLuhan’s Diary in 1930, Herb McLuhan gave a talk that year to the same sort of group Elsie was regularly performing before. His talk was titled “The Higher Plain”. ↩

- Some entries from McLuhan’s diary reported by Gordon: “I must, must, must attain worldly success to a real degree. It seems inconsistent I know to wish for such things and yet have your trust in God” (March 19, 1930, Gordon 22); “I have never known what it was to have a mother and Mother maintains that I have never had a ‘man’ for my father” (July 1, 1930, Gordon 22); “cruel fate that ever mated Elsie Hall and Herb McLuhan” (April 1, 1931, Gordon 24). In later life, McLuhan exhibited these bents of both his parents, in spades. While he was driven to communicate his thought in a way reminiscent of Elsie, he was also strangely placid, like Herb, in the face of inanities. ↩

- Brackets have been added around the phrase “yet, to all save the seer, behind life” to highlight the contrast, emphasized in the original, between ‘in‘ and ‘beyond‘. ↩

- What they are not: either fragments with no intimation of meaning beyond themselves, to be made of what we will; or fragments with intimation of meaning beyond themselves but none in themselves. These ‘wings’ correspond to the bents of Elsie and Herb, of course. ↩

- “To arrive where you are, to get from where you are not”, Four Quartets, East Coker — following San Juan de la Cruz, “para venir a lo que no eres, has de ir por donde no eres”. ↩

- At the end of the day, this perception depends from “the main question“. ↩

- Hopkins: “For good grows wild and wide”, from an untitled poem which the editor of his poems, Robert Bridges, called On a Piece of Music. ↩