The following is a post at the Northrop Frye blog, The Educated Imagination, which is archived here since that blog is now largely inactive. The editor’s notations are italicized.

***

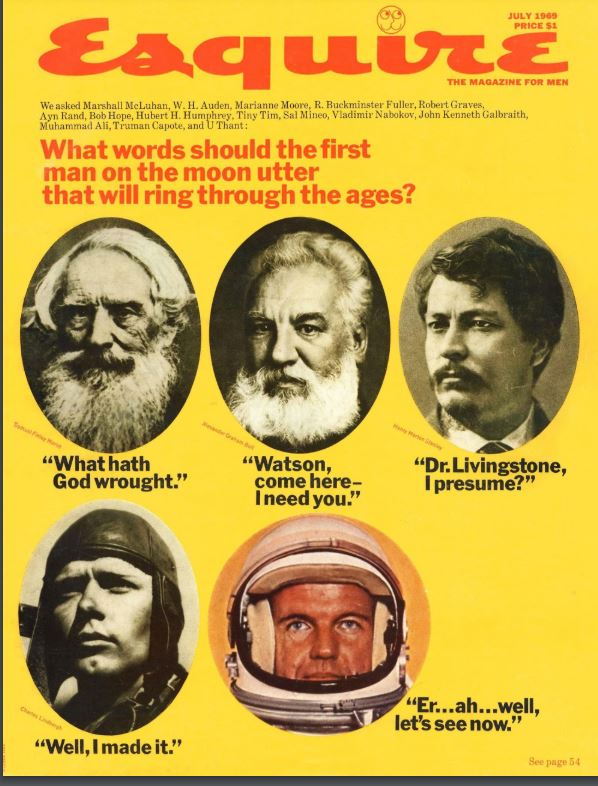

Of the twenty-nine volumes of Frye’s Collected Works, there are references to McLuhan in twenty-three of them, from his 1949 diary to the late notebooks of the 1980s and one of his last interviews in November 1990. Here they are.

1940s

From the 1949 diary:

Norma Arnett came up to me last night & wanted to know why a poem she (and I remember to some extent) thought was good had not been considered even for honourable mention in the Varsity contest. . . I said the judge was just plain wrong (I think it was McLuhan, so it’s a reasonable enough assumption). (CW 8, 94)

Marshall McLuhan went after me [regarding a paper on Bacon’s essays] with talk about essences & so on –- Helen Garrett reported back from Jack that he’d said he was out to get me. He didn’t quite, though a stranger would have been startled by his tone. Actually, I imagine he agreed with a fair amount of the paper, though he didn’t say so when I went home with him. . . McLuhan again on his anti-English line –- I think Jack Garrett is right in regarding it as a phobia. (CW 8, 143)

McLuhan did say something after all yesterday, about Germans. Said when a German met another human being it was like a root meeting a stone: he had to warp & twist himself into the most extraordinary convolutions to get around to the unpleasant fact of someone else’s existence. (CW 8, 145)

McLuhan’s Forum article [“Color-bar of BBC English”] suggests that he suffered abominably from the kind of self-consciousness he denies. (CW 8, 168)

Went for lunch with McLuhan and Ned [Pratt]. . . McLuhan brought up the subject about his magazine [about media communications] again. (CW 8, 209)

1950s

From the 1950 diary:

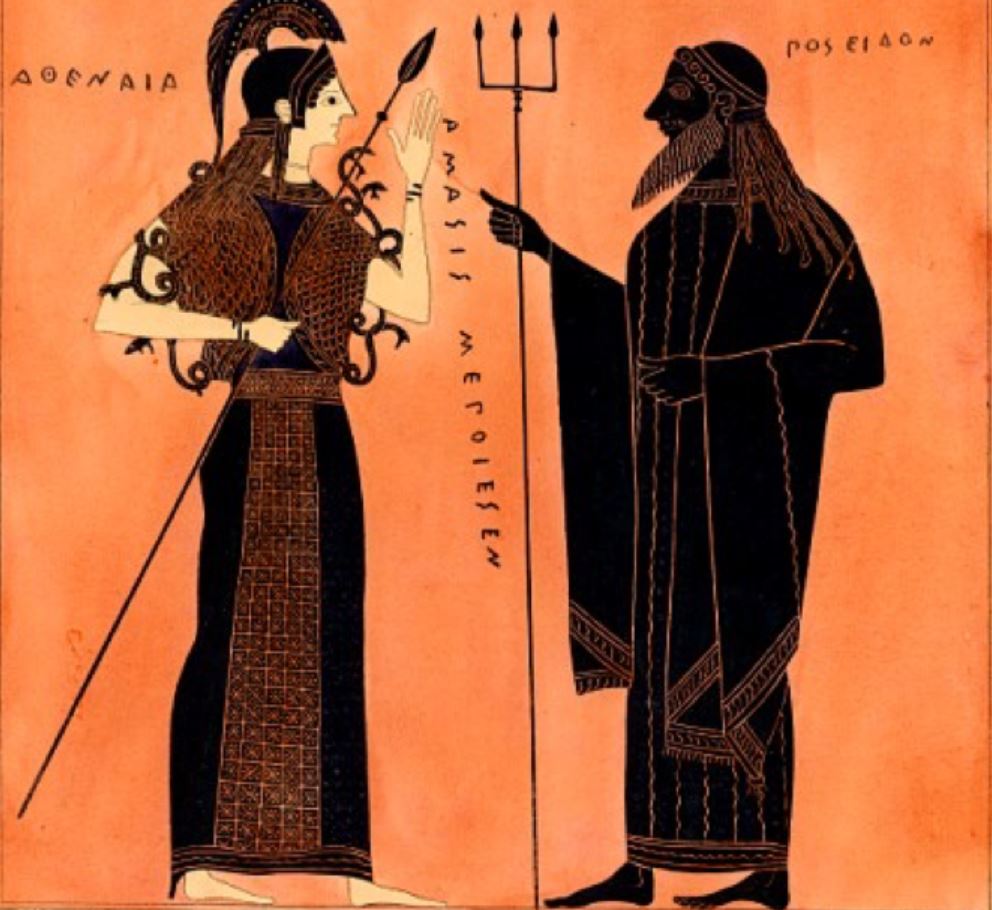

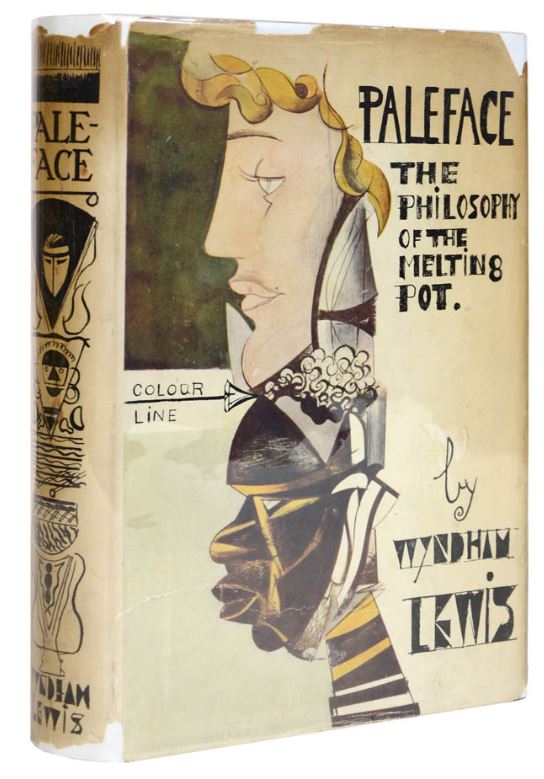

Marshall talked quite well about Wyndham Lewis: first he read a statement, in rather stilted language, about Lewis’ conception of the mask, & then read some amusing bits from the autobiography. . . Considering that Lewis at Rugby got a cup the boys give for six floggings in one day (after getting five & finding the day nearly at an end, he went & bounced a tennis ball against the headmaster’s door) & was kicked out of the Slade in two weeks, I don’t know if Toronto’s attitude was as provincial as he seems to think. (CW 8, 262)

McLuhan said the medieval critics distinguished epic from romance on the ethos-pathos basis –- the association of romance & pathos (passivity, stress on event) made me prick my ears, & I must look into it. (CW 8, 316)

From Notebook 33 (1946-1950/1953-1956):

The detective story is therefore a conservative form: it demonstrates the rightness of society vis-a-vis the criminal. The people who like them best are people who are confident of the essential solidity of the social order, or try to be & seek their reassurance from the detective story. As McLuhan pointed out to me, the detective is a man-hunter, & has about him the glamour of the F.B.I, the London bobby, the Canadian Mounties, & so on. Sherlock Holmes wears a hunting cap. (CW 15, 75)

From the 1952 diary:

I told Marshall that anything I said about any writing I was going to do was just official communique & meant go ‘way & don’t bother me, & he said he’d heard that was the line I took with the Guggenheim Committee. I don’t know who told him. . . Marshall has a tremendous fund of literary gossip. (CW 8, 385)

They [a number of colleagues at a party] discussed a recent article by Al Capp in Life announcing that he wasn’t going to be America’s only good social satirist any more, because he (or his syndicate, I couldn’t make out which) thought that satire was getting un-American. . .

They debated whether it was ironical or not, & it was suggested that the recent marriage to Daisy Mae meant he was going in exclusively for domestic humour. But Marshall pooh-poohed the idea: he said Cappy was just getting started, beginning with the projected birth of a son on July 4 called Yankee Doodle Yokum. (CW 8, 562-3)

In the morning I managed to waste time collecting the committee for Sanborn’s exam. Roper, McLuhan, [Norman] Endicott & myself, in Endicott’s office. McLuhan suggested a single overall question, which I had to fight. It’s bad enough having having to struggle with Woodhouse over exam questions, trying to get something that’s less Woodhouse party line, trying to make him see that what he’s not interested in isn’t necessarily always peripheral to the subject, and now here’s Marshall, a worse party-liner even than Woodhouse. His question followed exactly the general outline of (a) his course (b) Hugh Kenner’s book on Pound, and even though Sanborn had taken the course I thought it was bad for discipline to accept the single-question formula. Marshall didn’t give in too gracefully, identifying me with Toronto prissiness as he did so. (CW 8, 576)

From the Anatomy of Criticism notebooks (c. 1952/1953):

Marshall McLuhan says that Sidney regarded the prose epic, the Cryopaedia, More’s Utopia, & so on, as the highest form of literary art, & that that was the highbrow attitude as opposed to Spenser’s middlebrow attempt to combine popular romance & sound doctrine. This, naturally, is pretty speculative, but the existence of the conception of a prose epic in Renaissance criticism is something I badly need. Also as providing a link with the other half of rhetoric: oratory, & so of the assimilation of the hero to the prophet via oratory: the existential situation clarified by epiphany being, as in the Incarnation, also a historical “occasion.” (CW 23, 139)

From the 1955 diary:

Carpenter’s Explorations 4 is out, in a most handsome Kandinskyish cover. It has my archetypes thing and Miller MacLure’s Dylan Thomas article, but is otherwise as silly as ever. Except that article by Ong saying the Hebrews talked in terms of the ear & the Greeks the eye, & our conceptual language has got steadily more spiritual as ever, let the cat out of the bag as far as Marshall’s main thesis is concerned. I mean, now I know what he thinks he’s talking about. Back to oral tradition, the ear, and the Word of God. . .

Marshall has issued [his privately published pamphlet] “Counter Blast”: his love affair with the twenties is getting indecent. (CW 8, 606)

1960s

From “Comment” (1961):

Father Ong refers to my colleague Professor Marshall McLuhan, who is one of the few contemporary critics to realize another axiom: at no point can the criticism of contemporary literature be separated from the study of the whole verbal culture of our time, which includes, of course, the whole verbal anarchy of our time. (CW 29, 171)

From “The Drunken Boat” (1963):

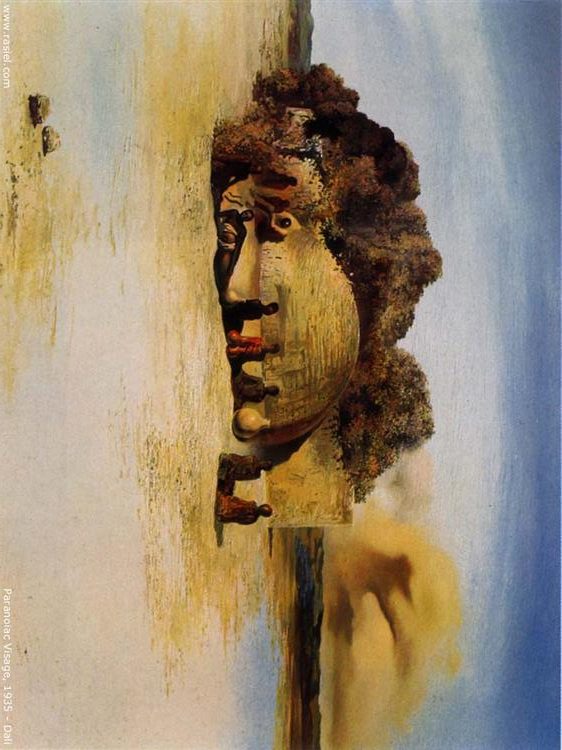

In Rimbaud, though his bateau ivre has given me my title, the poet is se faire voyant, the illuminations are thought of pictorially; even the vowels must be visually coloured. Such an emphasis has nothing to do with the pre-Romantic sense of an objective structure in nature: on the contrary, the purpose of it is to intensify the Romantic sense of oracular significance into a kind of autohypnosis. The association of autohypnosis and the visual sense is discussed in Marshall McLuhan’s book, The Gutenberg Galaxy. Such an emphasis leads to a technique of fragmentation. (CW 17, 90)

From “The Changing Pace in Canadian Education” (1963) :

In a book which many of you have seen, The Gutenberg Galaxy, Professor Marshall McLuhan speaks of contemporary society as a postliterate society; that is, a society which has gone through a phase of identifying knowledge with the written word and is now gaining its knowledge from all kinds of of other media which affect the ear as well as the eye. The ability to twitch ears is the mark of the animal which is constantly exposed to danger, and Mr. McLuhan is well aware of the context to which the increase in such media brings with it an increase in panic. He quotes one or two examples of panic in contemporary writers, including some intellectually respectable ones, and remarks, “Terror is a normal state in an oral society, because everything is happening to everyone all the time.” This sense of panic is occasionally rationalized on the level of practical intelligence itself, by people who speak of commitment as though it were a virtue in itself: don’t just stand there, get yourself committed. This is the attitude which was described many years ago by H.G. Wells as the “Gawdsakers” –- the people people who continually say, “For Gawd’s sake, let’s do something.” (CW 7, 174)

From “The Road of Excess” (1963):

I still have a copy of Blake that I used as an undergraduate, and I see that in the margin beside this passage I have written the words “Something moves, anyhow.” But even that was more of an expression of hope than considered critical judgement. This plotless type of writing has been discussed by a good deal of other critics, notably Hugh Kenner and Marshall McLuhan, who call it “mental landscape,” and ascribe its invention to the French symbolistes. But in Blake we not only have the technique already complete, but an even more thoroughgoing way of presenting it. (CW 16, 318)

From Notebook 19 (c. 1964-1967):

The opposite of verbal perception is the presentation, the communicated message, what Marshall talks about. Marshall says it’s the form & not the content of the message that’s important, which is why the nature of the medium is also important. It seems to me that the form has this importance only as long as we’re unconscious of it: to become aware of the form as a form is to separate the content. At that point the presentation goes into reverse & becomes a perception: the form comes from us then.

Such a reversal of movement. . .is of course a hinge of all my thinking. Marshall’s “extensions of man” version of it comes from Samuel Butler. A jet plane can move faster & a computer thinks faster than a man, but no machine yet invented has any will to do these things. The will is the reversal of movement from a receptive response stimuli to a Gestalt. No machine can yet make this reversal: no camera, in Blake’s phrase, can look through its lens. I have a feeling that Marshall doesn’t get past the presentation at all, but I’m doubtless wrong. (CW 9, 15)

Roman Catholic education has always been summa-centred, for obvious reasons. In Newman all humanism & individual-centred education has to be sacrificed on the summa altar, or else. Hence Catholic intellectuals go in for great co-ordinating patterns, but are too timid & anxiety-ridden to try to get beyond this point. Or else, like Marshall, they work out their own line on the assumption that the summa is in the background ready to take care of it. (CW 9, 28)

I think my body-and-extensions of body might be a central theme in the McMaster lectures, in view of the importance of abstract extension in Canadian landscape and (McLuhan) thought & culture. (CW 9, 34)

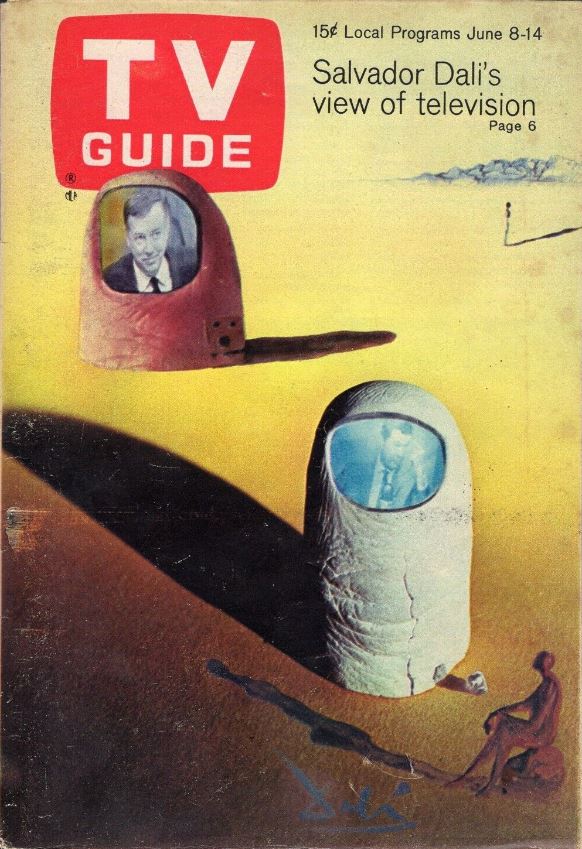

I haven’t yet read Marshall’s “the medium is the message” book, but. . .there is something magnifying in an address to the ear alone, something that reduces scale on a purely visual level. Hearing Hitler’s 1939 speeches was a terrifying & hideous experience. . . .but I wonder if he could have survived television. For in television you can turn the sound off, & that would reduce Hitler to Charlie Chaplin in no time. (CW 9, 38)

Marshall says everything we do today is a potential item in a computer information file: cf. archaeology, & some history, which shows so obviously an apocalyptic perspective on the past. (CW 9, 65)

Two things to get rid of. It’s no use saying I like resemblances more than discriminations: literature is an art & identity and resemblances are positive. Again, it’s no use saying my genres are a false analogy to biology just because it’s impossible to work out an a priori theory that things must be so. Even if you start with a completely chaotic view of art, like McLuhan’s view that art is anything that A can put over on B, the next step will tell you that putting over involves the conventionalizing of what you say, & so genres arise. (CW 9, 95)

From “Speculation and Concern” (1965):

I speak of course of the arts in the plural because there is a group of them: music, literature, painting, sculpture, architecture, perhaps others. The dance, for instance, is in practice a separate art, though in theory it is difficult to see it as anything but a form of musical expression. It seems inherently unlikely, at the time of writing, that we have yet to develop a new art, despite all the strenuous experiment that there has been, some of it in that direction. Marshall McLuhan says of the new media of communication that “the medium is the message,” and that the content of each medium is the form of another one. This surely means, if I understand it correctly, that each medium is a distinctive art. Thus the “message” of sculpture is the medium of sculpture, distinct from the message which is the medium of painting. But, as McLuhan also emphasizes, the new media are extensions of the human body, of what we already do with our eyes and ears and throats and hands. Hence they have given us new forms or variations of the arts we now have, and the novelty of these forms constitutes a major imaginative revolution in our time. But though distinctive arts they are not actually new arts: they are new techniques for receiving the impression of words and pictures. (CW 7, 248-9)

From the “Conclusion to the First Edition of Literary History of Canada” (1965):

What is perhaps the most comprehensive structure of ideas yet made by a Canadian thinker, the structure embodied by Innis’s Bias of Communication, is concerned with the same theme, and a disciple of Innis, Marshall McLuhan, continues to emphasize the unity of communication, as a complex containing both verbal and non-verbal factors, and warns us against making unreal divisions within it. (CW 12, 349)

Marshall McLuhan speaks of the world as reduced to a single gigantic primitive village, where everything has the same kind of immediacy. He speaks of the fears that so many intellectuals have of such a world, and remarks amiably: “Terror is the normal state of any oral society, for in it everything affects everything all the time.” The Canadian spirit, to personify it as a single being dwelling in the country from the early voyages to the present, might well, reading this sentence, feel that this was where he came in. In other words, new conditions give the old ones a new importance, as what vanishes in one form reappears in another. (CW 12, 371)

From “Style and Image in the Twentieth Century” (Broadcast 14 March 1967: interview with Murray MacQuarrie):

MacQuarrie: I suppose emotionally I’m a Tory in that I think that the sense of identity and sense of completeness you derive from existing within a dogmatic structure are a more benevolent and therapeutic thing than the experience of simply existing in an open field of dialogue — shall we say in a world now where there is nothing to do but communicate and where the content of the communication is largely disappearing. That’s a reactionary view: I suppose like many critics and academics the reactionism is an occupational hazard isn’t it?

Frye: Yes. Well, it’s partly that this McLuhan world, where the medium is the message, means that, when communication forms a total environment, nothing is really being communicated. What there is is really just an ambiance of noise. Out of that noise a single, genuine effort at communication — that is, something intelligible being said by A to B — cuts across with a kind of vividness which is perhaps unparalleled in history. The role of genuine communication becomes much more obvious and immediate once this tremendous roaring environment of false communication has been set up by the mass media. When I speak of an open mythology, I am not saying that we’ve entered a civilization which is completely relative and where there can be no standards and no doctrine and no real beliefs or convictions any more. That seems to me to be nonsense. That’s the exact opposite of what I’m talking about. There is no difference between an open mythology and a closed one except in the difference that society makes of it. The real way to strengthen one’s beliefs and convictions and to make the axioms of one’s belief not merely a professed creed, but the real principles underlying one’s conduct, is to regard them as under the judgment of dialogue and “the Parliament of man,” as still something that can always be liberalized, made flexible, and fill with the love and respect for other people which the open-sidedness of the myth makes possible. (CW 24, 56-7)

From “Dix An savant la Néo-critique” (Conducted late April 1967):

Frye: Je pense que McLuhan ne distinguée pas suffisamment entre l’attitude active et l’attitude passive, entre less possibilities nouvelles que la technique nous offer et les dangers qu’elle suscite. Le cult de McLuhan prend son point de depart dans l’illusion du progress. Il donne l’impression que les medias donnerant naissance a une nouvelle civilisation. Voila qui n’est point prouvé. Tout dépendra de la maniere dont la société fera usage de ces medias. (CW 24, 61)

From The Modern Century (1967):

The role of communications media in the modern world is a subject that Professor Marshall McLuhan has made so much his own that it would be almost a discourtesy not to refer to him in a lecture which covers many of his themes. The McLuhan cult, or more accurately the McLuhan rumour, is the latest of the illusions of progress: it tells us that a number of new media are about to bring in a new form of civilization all by themselves, merely by existing. Because of this we should not, in staring at a television set, wonder if we are wasting our time and develop guilt feelings accordingly: we should feel that we are evolving a new mode of apprehension. What is important about the television set is not the quality of what it exudes, which is only content, but the fact that it is there, the end of a tube with a vortical suction which “involves” the viewer. This is not at all of what a serious mind and most original writer is trying to say, yet Professor McLuhan lends himself partly to this interpretation by throwing so many of his insights into a deterministic form. He would connect the alienation of progress with the habit of forcing a hypnotized eye to travel over thousands of miles of type, in what is so accurately called the pursuit of knowledge. But apparently he would see the Gutenberg syndrome as a cause of the alienation of progress, and not simply as one of its effects. Determinism of this kind, like the determinism which derives Confederation from the railway, is a plausible but oversimplified form of rhetoric. (CW 11, 20-1)

From “A Meeting of Minds” (1967):

It is particularly important for Marshall McLuhan to have this kind of space [The Centre for Culture and Technology] around him because he is a very enigmatic and aphoristic type of thinker, an easy person to distort and misunderstand. On the periphery there is a large McLuhan rumour which says, “Nobody reads books any more –- Marshall McLuhan is right.” This, of course, is something of an oversimplification of what a quite important person has to say. So I think it is important for the university to have a structure that will permit serious and dedicated people to get a bit closer to him, not only to understand him, but so they can work out their own ideas in some kind of reference to his. (CW 7, 307)

From “Literature and Society” (1968):

As you all know, within recent times another colleague of mine at Toronto, Marshall McLuhan, has attacked the same question on a much broader front. He has pointed to the immense impact that other media of communication besides books are now making, and has drawn from his observation of this impact the principle, which seems sound enough in itself, that we are returning to some of the social features of a preliterate culture, which means a retribalizing of society, as he calls it, hence his phrase about the global village. What worries me about this thesis is the way in which it has been received by what I call the Eros mentality of the American public. A facile and shallow optimism, a belief in automatic progress, a confidence that a new civilization can be brought about by certain gadgets merely because the gadgets are there, is always close to the surface of American feeling. Along with it goes a constant wish to abdicate moral dignity and responsibility. I am not speaking of McLuhan himself here, but there is one feature in his writing that seems to me to help to encourage such a response, the feature that I have called determinism. I have learned to distrust all determinisms, whether they are economic or religious or mediumistic: they seem to me essentially theoretical devices, which help to make a doctrine more popular and easier to grasp. New media of communication are not causes of social change: they are only the conditions of change, and we cannot discover the direction of social change from them; it is society itself that will determine the direction of change. (CW 27, 277)

As soon as oral and preliterate characteristics make themselves felt in society, a patriarchal figure is likely to make his appearance in the middle of that society. This patriarchal figure may be at first simply an amiable figurehead (Eisenhower), or counter-tendencies in society may throw up opposing symbols of youth and energy (Trudeau, the Kennedys); but if society does not arrest the drift it is likely to go from King Log to King Stork, from reassuring images to Big Brother. Considering McLuhan has very explicitly warned us against this danger, it would be unfairly ironic if he were to become the Pied Piper of our generation. (CW 27, 278)

From “The Social Context of Literary Criticism” (1968):

The strong centrifugal drift away from criticism into other subjects, which had set in at least as early as Coleridge, continues in our own day. Sometimes this drift represents a genuine expanding of the scope of criticism, or even, as with my Toronto colleague Marshall McLuhan, a new mosaic code. But it often take the form of treating the work of literature as an illustration of something outside literature. (CW 10, 348-9)

From “Research and Graduate Education in the Humanities” (1968):

There is, of course, a superstition in our time that this complex, configurated, and, in a sense, mythical thinking is something that can only be brought to us from the new media. I happen to be on a board in Canada concerned with communications, and this board had a committee of policy report to it which recommended that the board should issue publications from time to time. The sentence with which it began this recommendation read: “Despite the disadvantages inherent in the linear representation of a world that is increasingly simultaneous, print still retains its medieval authority.” This sentence, I suppose, is typical of the kind of nitwitted McLuhanism which is confusing the educational scene. McLuhan himself, of course, is another matter, but I think that even he fails to distinguish between the actual operation of reading a book, which is linear, turning over the pages, and following the lines of type from the upper left-hand corner to the lower right, and the effect of a book on the mind as a unity, once read. As that, the book is, and in the foreseeable future will remain, the indispensable tool of the scholar in the humanities. (CW 7, 340)

From “L’Anti-McLuhan” (Conducted 14 November 1968: interview with Naim Kattan):

Kattan: Le livre est-il condamné?

Frye: Non, malgré ce que dissent les imateurs de McLuhan. On a beaucoup simplifié la pensée de ce dernier. Il y a point sur lequel je ne suis pas d’accord avec lui. Il dit que le livre est linéaire et que notre culture est simultanée. Mais la il confound la lecture d’une livre et l’impact excercé par cette lecture, une fois terminée. On lit un livre d’une maniere linéaire, page per page, mais une fois la lecture terminée l’impact s’excerce d’une maniere simultanée. (CW 24, 76-77)

From “Canadian Literature and Culture” (c. late 1960s):

McLuhan’s development out of Innis: Innis’ thesis about the control of communications by an ascendant class never came through clearly, because Innis himself wasn’t committed enough to understand his own real argument. The university was his garrison, and he was perhaps the last major example of that in Canadian life. You can’t hold a vision of that size and scope steadily without more commitment to a society as a whole than he had. McLuhan of course was the other extreme: he got on the manic-depressive roller coaster of the news media, so he was unreasonably celebrated in the early sixties and unreasonably neglected thereafter. (CW 25, 199)

McLuhan would perhaps have remained unknown if he had talked of the global town (although he does use the FW phrase “the urb it orbs,” or global city). (CW 25, 234)

From “Criticism and Society” (c. late 1960s):

But when I look at the books on the shelves of my study, it does not seem as though the criticism of the other arts was the field into which literary critics naturally expanded when they began to deal with larger and broader issues. I can see in front of me on the walls of my study such books as Lionel Trilling’s Beyond Culture, Leslie Fiedler’s An End to Innocence, Irving Howe’s Steady Work, Marshall McLuhan’s Understanding Media. These are all books written by literary critics. They all deal with matters considerably removed from literary criticism and yet they say about them the things that a person trained in literary criticism would look for and would naturally say. (CW 10, 229)

From “Engagement and Detachment” (Filmed 1968: interview with Roby Kidd and D.M. Smyth):

Smyth: Do you think that in the field of education our approach to rhetoric or rhetorical skills is sufficiently sophisticated for people to understand the subtleties of modern forms of communication?

Frye: They could be sophisticated and subtle enough — yes. I would strongly agree with Marshall McLuhan, who is saying very different things from what a lot of people think he’s saying, when he says that one of the central duties of education is to provide “civil defence against media fallout.” That’s his phrase. (CW 24, 70)

From “The Only Genuine Revolution” (Recorded 30 December 1968: interview by Bruce Mickelburgh):

Frye: [I]t seems to me that one reason for studying rhetoric is to show the student how advertising is a form of rhetoric and what its means of rhetorical persuasion are. Most sensible adults take advertising rather ironically as a kind of game. They respond to it all right — they’ll buy the car— but I think they can distinguish reality from illusion to that extent. I should think, though, that for somebody of the age of ten or twelve it might come as something of a shock of disillusionment to find out that advertising does not in fact mean what it says, is never intended to mean what it says. It seems to me that’s the age level at which one can bring about a revolution in one’s attitude to language far deeper than conventional literature can make at that age.

Mickelburgh: How would you go about doing that?

Frye: I would simply give them advertisements — the technique of Marshall McLuhan’s Mechanical Bride. Just say, “Now what forms of persuasion are being used in this ad? What sort of person are they trying to make you pretend you are?” (CW 24, 166-7)

From Notebook 12 (1968-70):

McLuhan has of course enormously expanded my thesis about the return of irony to myth. His formulation is hailed as revolutionary by those who like to think that the mythical-configuration-involved comprehension is (a) with it (b) can be obtained by easier methods than by use of intelligence. Hence everyone who disagrees (as in all revolutionary arguments) can be dismissed as linear or continuous. But there are two kinds of continuity involved: one is the older detached individuality, the other the cultural and historical continuity of preserving one’s identity and memory and moving from one to the other. The issue here is a moral issue between freedom of consciousness and obsessive totalitarianism, plunging into a Lawrentian Dionysian war-dance. (CW 9, 145)

When I settled into my real line I naturally wanted to be “great” there too: but maybe the great mind is obsolete. . . [S]omething about greatness ended around 1940. We’re doing different things now. Marshall McLuhan is a typical example: a reputation as a great thinker based on the fact that he doesn’t think at all. (CW 9, 146)

And, of course, I’m doubling back on my criticism of McLuhan. Centrifugal meaning tends to be sequential & linear: the Logos as (a) discursive logic (b) history or sequence of events. Centripetal meaning leads to thematic stasis. Here we have the simultaneous perception that takes off from recognition: totality of metaphor mandala diagrams included. (CW 9, 184)

The theoretical aim of the verbal icon stage is the vision of the poem’s unity, but explication is so preoccupied with retracing the process of reading that it often doesn’t get that far. The first line [centripetal meaning] is the McLuhan axis, the communication determinism balanced by the extreme formalism of identifying medium and message. (Of course he goes into the second stage [centrifugal meaning] a good deal too.) (CW 9, 188-9)

Of course the foreground antithesis, a very minor one, is the contrast represented by McLuhan and myself. I hold to the continuous, encyclopedic, linear-narrative Christian structure, and, of course, “discontinuous” is very much an in-word at present. There is no such thing as a discontinuous poem, though there are poems, like Pound’s Cantos, that try to force the reader to establish the continuity of what he’s reading, instead of providing it for him ready-made. (CW 9, 232)

[T]he more I think about McLuhan’s obiter dicta, the more the exact opposite of what he says seems to me to be true. As I say earlier in this notebook, the oral tradition is linear: we’re pulled along by it in time, & at the end there’s nothing. Writing provides a spatial focus: the process of reading a book is linear, but at the end you have the “simultaneous” possession of the whole thing. Also in a newspaper. That’s why writing is democratic, potentially: the oral tradition is much closer to the mob, with its easy access to “lend me your ears” rhetoric. Its revival today goes with anarchism, and also with unscripted improvised dramas, music, and socio-political “happenings.” (CW 9, 237)

From “Sign and Significance” (1969):

The process of explication is consequently easiest to follow, and best organized, when it starts with a sense of the poem’s unity and works deductively from there. Explication sometimes gets so involved in retracing the process of reading, and with mapping out the intricacies of ambiguity and the like encountered on the way, that it tends to lead one away from the sense of unity. McLuhan, again, reflects this difficulty, which he makes the basis of a distinction between print and electronic media. This is of course a technical difficulty only, but explicators who have been most successful in overcoming it, such as Spitzer and Auerbach, raise implicitly other questions of theory. (CW 27, 297-8)

In Marshall McLuhan, who was trained essentially in this school as a [New] critic, an extreme and somewhat paradoxical formalism, which identifies medium and message, has been placed in a Neo-Marxist context of determinism in which communications media play the role that “means of production” do in more orthodox Marxism. A good many traces of an older religious determinism can be found in The Gutenberg Galaxy (CW 27, 298)

From “CRTC Guru,” (Conducted December 1968-July 1969: interview with Rodrique Chiasson):

Frye: May I talk at random for a minute, and if I get anywhere that’s of some use to you then just say so. There’s a paradox in oral communication that looks for two contradictory things: one is detachment, the other is involvement. . . News should be reported objectively and create a mood of detachment in the viewer. There are other things which demand his concern, his involvement. In a drama, the attempt is normally to involve the watcher in a story. On the other hand you have people like Brecht saying that what he wants is to chop holes in the rhetorical façade, to alienate his audience so that they will be detached from the play and in command of their own souls. If you had an incompetent Brecht, what he would produce would be almost identical with the ordinary television program which is interrupted every five minutes by a commercial. Now it seems to me that the way to genuine detachment is not through interruption but through the building up of very small organizations, in a discontinuous sequence. I’m not speaking of discontinuity in the sense of not having sequence, I’m speaking rather of the rhythm in the sequence. If a man writes a book, he’s writing a continuous piece of prose, and you keep turning over the pages, from one paragraph to another; but if he’s a wise man, a guru, an oracle, what he will do is talk in a series of detached paragraphs. That’s an oracular style: it has been from Heraclites to Marshall McLuhan. There are pauses between each remark and this pause requires a great deal of concentration, but it also leaves you in command of your soul. (CW 24, 113)

From “The Limits of Dialogue” (Broadcast 19 February 1969: interview with Eli Mandel):

Frye: Many religious thinkers are convinced that there is [a dialectic as well as a dialogue with God]. For example, Martin Buber, in speaking of the I-Thou relationship in religion, says that the dialogue is really the central form of religious experience. It seems to me that this doesn’t happen only in religion. It happens whenever anybody writes a book and presents it to the public. It looks as though a book written entirely by one person is a dictatorial or authoritarian kind of monologue, where the writer is simply holding your buttonhole and not letting you go until he’s finished. But actually the written sequential treatise is a very democratic form of dialogue with the reader. The author is putting all his cards on the table in front of you. He has made his response to the subject with which he has been in dialogue. He is not transmitting the possibility of dialogue to his reader. If he has really retreated into the upper limits of silence, then he will not write continuously. He will write in separate paragraphs, that is, in aphorisms, or detached oracular utterances. Oracular writers, from Heraclitus to Marshall McLuhan, have always written prose of that kind, that is, in separated sentences, where every sentence is surrounded by a bit packet of silence. (CW 24, 176)

From Notebook 11f (1969-70):

In my early Yeats paper I talked about a hyper-physical world. . .of unseen beings, angels, spirits, devils, demons, djinns, daemons, ghosts, elemental spirits, etc. It’s the world of the “inspiration” of poet or prophet, of premonitions of death, telepathy, extra-sensory perception, miracle, telekinesis, & a good deal of “luck”. . . Fundamentally, it’s the world of buzzing though not booming confusion that the transistor radio is a symbol of. The world of communication which inspires terror. . . Before we come out on the other side of it we recognize the ordinary life as part of it, a Bardo perspective out of which apocalypse, or stage 2, finally comes. It’s the polytheistic world of contending & largely unseen forces; it’s the world of terror that McLuhan associates with the oral stage of culture: twitching ears, & a poor sense of direction. (CW 13, 90)

McLuhan’s medium & message formula was an effort to show that each medium is a mode of perception, & not just different ways of presenting the same content. But nobody seriously thinks of television as a viewer’s mode of perception; he thinks of it as his way (if he’s a producer of advertiser) of reaching a viewer. We were astonished when blacks started to smash & loot: we hadn’t thought of television as their way of seeing an affluent white society gorging itself on luxury goods & privileges. No matter how much he wants people to look at his product, the advertiser doesn’t realize that television is their way of looking at him, & not his way of reaching them.

So we still haven’t grasped the implications of the fact that contemporary unrest is middle-class dissatisfaction. If the medium is the message, & newspapers & magazines & radio & television all carry the same message, it follows that they’re all pretty much the same medium. McLuhan’s distinction of cool and low-definition media & their opposites is really a distinction between media where the mode of perception is an essential aspect & the modes that are primarily spectacular, like the movie & the ballet. Spectacular forms tend to a kind of entropy: the film avoided this by developing an “involving” vortex technique of symbolism that such in the viewer & puts him there–2001 was a corny but effective example. The drug cults have a lot to do with the desire to develop new modes of perception which the mass media have cheated & let down. (CW 13, 95-6)

The religious quest of youth today shows up in the search for human contact, encounter groups, folk singers, the sense of comradeship attained in demonstrations (of course it’s the enemy outside that makes it all so cuddly, not the friends inside.) Television is like a telescope, a new method of perception which tells us more, but also makes what it sees look cold, dead, and inconceivably remote. Global village my ass. (Every idea contains its own opposite or antithesis.)

The “flow of information,” which is mostly disinformation, is actually a presentation of myths. And people are increasingly rejecting the prescribed myths & developing their own counter-myths. Take another McLuhan phrase, “global village”–one early satellite broadcast was called the “town meeting of the world.” The myth behind this phrase assumes that every technological development creates a new anxiety & understanding–that a village is a community of friends. But, of course, a village may be a community of cliques & feuds & backbiting & gossip of a ferocity far worse than any metropolis, like those hideous little towns at the divisional points of railways, where the conductor’s wife couldn’t compromise her dignity by speaking to the brakeman’s wife. So when communicators, with a schoolteacher’s bright & glassy smile, say: now we’re going to be able to create a dialogue with Paraguay & Tanzania, & won’t that be nice? the reaction is, very often: we don’t want all those people in our living room: we want to get together with the people who speak our language & share our beliefs & prejudices, including, if we’re lucky, a minority that we can have fun of kicking around. Separatism, except when it is a genuine effort to escape from tyranny, is in most respects a mean, squalid & neurotic philosophy, but it is the strongest force yet thrown up by the age of total communication. (CW 13, 97)

From Notes 58-7 (1969/1975):

[H]aving worked with archetypes all my life, I feel that the world in which Jung’s unconscious forces emerge and threaten sometimes to overthrow the ego-consciousness is really an interpenetrating global village. Archetypes represent a world-wide language independent of time and space. The phrase global village made [Marshall] McLuhan famous, and the present eclipse of his reputation is due to the fact that people surmised that he was on to something, but got disillusioned by his apparent inference that the electronic media actually communicate news of this world, which they bloody well don’t. (CW 20, 249-50)

From Notebook 21 (1969-71):

The analogy of intuition is the idol of the cave; the analogy of intellect, which is also the aesthetic analogy, is the idol of the theatre. These are respectively the mother in the depths & the father in the sky: note that the eagle here is descending to a lower sky. The analogy of feeling, the sexual analogy that runs through Lawrence, Swinburne, Yeats, Nietzsche & Freud, is the idol of the tribe: what it creates is a blood-unit that is tribal, in the McLuhan sense. It’s Orc bound to the cycle, leaving the east void. The analogy of sensation, the empiric analogy that is founded on communication, is the marketplace. (CW 13, 176)

1970s

From “Rear-View Crystal Ball” (1970):

Marshall McLuhan has a phrase about reactionaries who don’t get with it as people driving by a rear-view mirror. This assumes the monumental fallacy that we move forward in time as well as space, whereas actually, of course, we face the past, and the rear-view mirror of that direction is the shape of things to come. (CW 12, 408)

From “Communications” (1970):

One common assumption of this fact [the revival of the oral tradition in the electronic age], strongly influenced by Marshall McLuhan, is that print represents a “linear” and timebound approach to reality, and that the electronic media, by reviving the oral tradition, have brought in a new “simultaneous” or mosaic form of understanding. Contemporary unrest, in this view, is part of an attempt to adjust to a new situation and break away from the domination of print. This view is popular among American educators, because it makes for anti-intellectualism and the proliferating of gadgets, and I understand that for some of them the phrase “p.o.b,” meaning print-oriented bastard, has replaced s.o.b. as a term of abuse. It seems to me that his view is not so much wrong as perverted, the exact opposite is true. . .

The domination of print in Western society, then, has not simply made possible the technical engineering efficiency of that society, as McLuhan emphasizes. It has also created all the conditions of freedom within society: democratic government, universal education, tolerance of dissent, and (because the book individualizes its audience) the sense of the importance of privacy, leisure, and freedom of movement. What the oral media have brought in is, by itself, anarchist in its social consequences. (CW 11, 137-9)

From “The Definition of a University” (1970):

I am often asked if a student today is different from his predecessors, and usually the answer expected is yes. The answer happens to be no. There has been a tremendous increase in the rain of sense impressions from the electronic media, and this has produced a considerable alertness and power of perception on the part of students. However, the power to integrate and co-ordinate these impressions is no greater than it was. This is a situation which has been interpreted by my colleague, Professor Marshall McLuhan, but I would regard his interpretation, if I have understood it correctly, as quite different from mine. He distinguishes between the linear and fragmented approach which he associates with the printed book and the total and simultaneous response which he associates with the electronic media. It seems to me, on the other hand, that it is the existence of a written or printed document that makes a total and simultaneous response possible. It stays there: it can be referred to; it can become the focus of a community. It is the electronic media, I think, which have increased the number of linear and fragmented experiences–experiences which disappear as soon as one has had them–and because of that, they have also increased the general sense of panic and dither in modern society. At the same time, there is no doubt that television and the movies have developed new means of perception, and that they indicate the need for new educational techniques which, as far as I know, have not yet been worked out. I did hear a lecture some time ago by an educator which began by showing the audience a television commercial. He then said, “There is one thing in that commercial which all of you missed and which all the young people to whom it was shown got at once.” I thought to myself, “Now we’re getting to something important. Now we shall find out how education is going to adjust itself to this situation.” But, unfortunately, all he said after that was, “This indicates a fact of great educational importance. We don’t know quite what it is, but we have it under close study.” (CW 7, 419-20)

From “The Quality of Life in the 1970s” (1971):

The 1960s were also a period of becoming adjusted to new techniques of communication, more particularly the electronic ones. It was the McLuhan age, the age of intense preoccupation with the effect of communications on society, and with the aspect of life that we call news. Many of the worst features of the late ’60s, its extravagant silliness, its orgies of lying, its pointless terrorism and repression, revolved around the television set and the cult of “image.” (CW 11, 290)

From The Critical Path: An Essay on the Social Context of Literary Criticism (1971):

During this period I had been an advisory member of the Canadian Radio and Television Commission, which had compelled me to think a certain amount about the relation of literary criticism to communication theory–somewhat unwillingly, as I had assumed that my colleague Professor Marshall McLuhan was taking care of that subject. Consistently with the main them of this essay, the references to McLuhan in it are less about him than about the social stereotypes of McLuhanism. (CW 27, 5-6)

More recently, Marshall McLuhan has placed a formalist theory, expressed in the phrase “the medium is the message,” within the context of a neo-Marxist determinism in which communication media play the same role that instruments of production do in more orthodox Marxism. Professor McLuhan drafted his new Mosaic code under a strong influence from the conservative wing of the New Critical movement, and many traces of an earlier Thomist determinism can be found in The Gutenberg Galaxy. An example is the curiously exaggerated distinction he draws between the manuscript culture of the Middle Ages and the book culture of the printed page that followed it. (CW 27, 12-13)

The difficulty in transferring explication from the reading process to the study of structure has left some curious traces in New Critical theory. One of them is in Ransom, with his arbitrary assumption that texture is somehow more important for the critic than structure; another is again in McLuhan, who has expanded the two unresolved factors of explication into a portentous historical contrast between the “linear” demands of the old printed media and the “simultaneous” impact of the new electronic ones. The real distinction however is not between different kinds of media, but between the two operations of the mind which are employed in every contact with every medium. There is a “simultaneous” response to print; there is a “linear” response to painting, for there is a preliminary dance of the eye before we take in the whole picture; music, at the opposite end of experience, has its score, the spatial presentation symbolizing a simultaneous understanding of it. In reading a newspaper there are two preliminary operations, the glance over the headlines and the following down of a story. (CW 27, 16)

The effect of discontinuity is to suggest that the statements are existential, and have to be absorbed into the consciousness one at a time, instead of being linked with each other by argument. Oracular prose writers from Herclitus to McLuhan have exploited the sense of extra profundity that comes from leaving more time and space and less sequential connection at the end of sentence. (CW 27, 27)

Both oral poetry and the life it reflects rely on a spontaneity which has a thoroughly predictable general convention underlying it. It is consistent with the kind of culture that young people should be concerned, in McLuhan’s formulaic phrase, more with roles than goals, with a dramatic rather than a teleological conception of social function. . . We thus have, among other things, new forms of social activity which are really improvised symbolic dramas. (CW 27, 100)

The revival of oral culture in our day has been variously interpreted, and one interpretation, suggested and strongly influenced by McLuhan, is that print represents a “linear” and time-bound approach to reality, and that the electronic media, by reviving the oral tradition, have brought in a new “simultaneous” or mosaic form of understanding. Contemporary unrest, in this view, is part of an attempt to adjust to a new situation and break away from the domination of print. We saw in the first section, however, that the difference between the linear and the simultaneous is not a difference between two kinds of media, but a difference in two mental operations within all media, that there is always a linear response followed by a simultaneous one whatever the medium. For words, the document, the written or printed record, is the technical device that makes the critical or simultaneous understanding possible. The document is the model of all teaching, because it is infinitely patient, repeating the same words however often one consults it, and the spatial focus it provides makes it possible to return on the experience, a repetition of the kind that underlies all genuine education. The document is also the focus of a community of readers, and while this community may be restricted to one group for centuries, its natural tendency is to expand over the community as a whole. Thus it is only writing that makes democracy technically possible. It is significant that our symbolic term for a tyrant is “dictator,” that is, an uninterrupted oral speaker.

The domination of print in Western society, then, has not simply made possible the technical and engineering efficiency of that society, as McLuhan emphasizes; it has also created all the conditions of freedom within that society: democratic government, universal education, tolerance of dissent, and (because the book individualizes its audience) the sense of the importance of privacy, leisure, and freedom of movement. Democracy and book culture are interdependent, and the rise of oral and visual media represents, not a new order to adjust to, but a subordinate order to be contained. What the oral media have brought in is, by itself, anarchist in its social affinities. They suggest the primitive and tribal conditions to a preliterate culture, and to regard them as a new and autonomous order would lead, once again, to adopting a cyclical view of history, resigning ourselves to going around the circle again, back to conditions we have long ago outgrown. . .

It is all very well to say that the medium is the message, but as we seem to get much the same message from all the media, it follows that all media, within a given social environment like that of the Soviet Union or the United States, are much the same medium. This is because the real communicating media are still, as they always have been, words, images, and rhythms, not the electronic gadgets that convey them. The differences among the gadgets, whether they are of high or low definition and the like, must be of great technical interest, especially to those working with them, but they are clearly of limited social importance. If a country goes to war after developing television, the use of a “cooler” medium does not, unfortunately, cool off the war. The identification of medium and message is derived from the arts: painting, for instance, has no “message” except the medium of painting itself. But it is a false analogy to apply this principle to interested, or baited-trap, communication from A to B. There, one identifies form and content only as long as one is relatively unconscious of the form and still bemused by its novelty: but in direct communication, as soon as one becomes aware of the form, the content separates from it. (CW 27, 103-5)

From “Reviews for the CRTC” (1971-2):

[With reference to Sesame Street] McLuhan says that the content of a medium is the form of an earlier medium. This seems to me an unnecessarily inaccurate way of saying that the real units of communication have always been words and pictures, for which television is simply a new frame. Now of course words and letters, in the hieroglyphic stage, were also pictures, so that writing and drawing were originally the same art. Both Sesame Street and the science program brought out this original identity of word and image very clearly.

There is a reversal of this principle that leads to some consideration of the interaction of eye and ear in television. Television is primarily a visual, and therefore a dramatic, medium. They etymology of the word “theatre” indicates its primitive connection with the eye. A visual or dramatic medium is “cool” in the sense that watching immobilizes the body. And while intense continuous listening immobilizes one too, one of the most primitive and central forms of aural message is the command, the starting point of action. Advertising used to try to incorporate this by pretending a kind of urgency: go right down to the store and demand Sudsy Soap. (CW 10, 280)

I suppose the lack of detachment is one of the things that is meant by calling television an involving medium. It is also a “cool” medium, in the McLuhan sense, not just because of the low definition but because of the absence of any sense of exhilaration or exuberance, such as the stage and cinema can so easily and so constantly produce. It seems to me very much a medium of objectified dream. (CW 10, 292)

In television, one wants, in general, a visual focus; but we don’t need an auditory focus. Voice-over and similar devices taking advantage of the fact that sound isn’t so definitely located as vision (what McLuhan calls auditory space) makes everything much more interesting and impressive. It is easy, quick, cheap, and lazy to provide an auditory focus too: in other words a talking head. (CW 10, 299)

From Notes 54-3 (c. 1972):

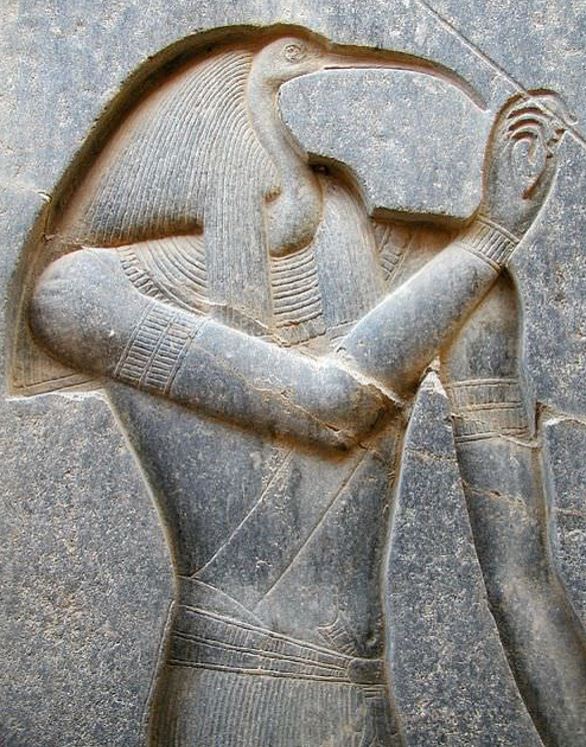

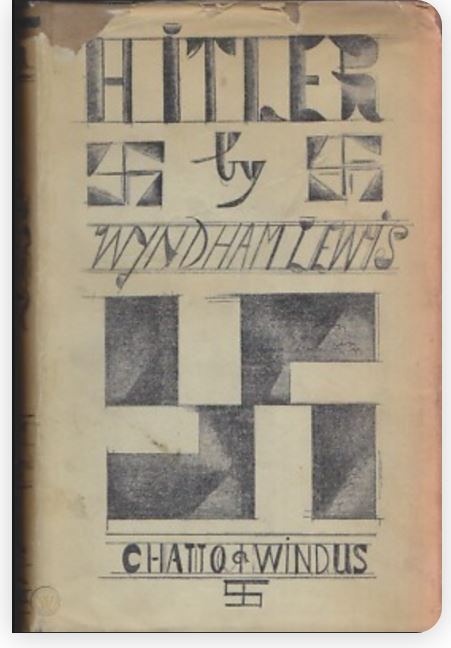

I think I realize now that what Spengler gave me was a sense of interpenetration of symbolism: everything that happens in the world symbolizes everything else that happens. Nobody had really established this before, though there are hints of it in Ruskin; today it’s a staple of pop-kulch McLuhan-Carpenter stuff, but they (at least McLuhan) got it through Wyndam Lewis, whose Time and Western Man is a completely Spenglerian book. (CW 15, 309)

“Harold Innis: Portrait of a Scholar” (Broadcast 21 November 1972: interview with Elspeth Chisholm):

Chisholm: Professor Northrop Frye is a literary critic and commissioner for the CRTC. He has long thought that Innis’s theories were central to any communications theory.

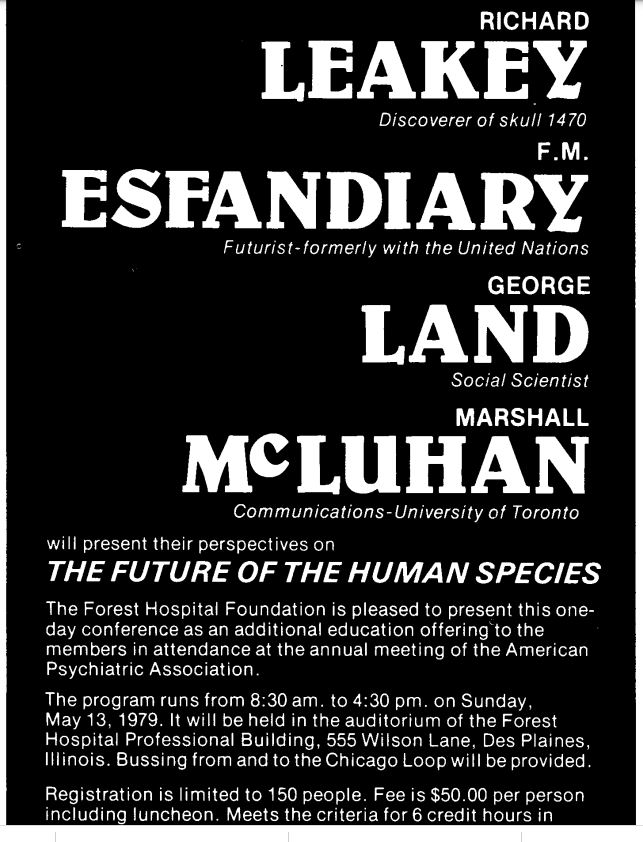

Frye: This is something that naturally interests both historians and theorists of language, so that Innis, like Hegel, is a person who has both left-wing and right-wing disciples. I don’t think that you could find greater contrasts in outlook and temperament in the University of Toronto than between, say, Marshall McLuhan and Donald Creighton, and yet both of them have been very strongly influenced by Innis. (CW 24, 283)

From “The Renaissance of Books” (1973):

If it were really true, as McLuhan and others have urged, that print is a “linear” medium, carrying the eye forward and hypnotizing all responses except the purely visual one of reading, there would be no difference between print and any other medium. But this thesis confuses the reading process with the consulting process, and overlooks the fact that print has a unique power of staying around to be read again, presenting, with unparalleled patience, the same words again however often it is consulted. It is therefore public access to printed and written documents that is the primary safeguard of an open society. (CW 11, 154)

From “The Search for Acceptable Words” (1973):

I am on a commission in Canada concerned with communications, and when I first joined it I read a policy report which recommended that publications should be issued from time to time. The recommendation began: “Despite the disadvantages inherent in the linear representation of a world that is increasingly simultaneous, print still retains its medieval authority.” This sentence is typical of the nitwitted McLuhanism (I am not speaking of McLuhan himself) which is confusing the educational scene. I recently spoke to an audience of university graduates, and was asked, quite seriously what I thought of the university’s building such a huge library when the book would be out of date by the time it was opened. The book qua book is not linear: we follow a line while we are reading it, but the book itself is a stationary visual focus of a community. It is the electronic media that increase the amount of linear experience, of things seen and heard that are quickly forgotten. One sees the effects on students: a superficial alertness combined with increasing difficulty in preserving the intellectual continuity that is the chief characteristic of education. (CW 27, 315-16)

Many Canadians, including Harold Innis and Innis’s disciple Marshall McLuhan, have been interested in the totality of communication, and the essential unity of its activity, whether it is building railways or sending messages. (CW 27, 328)

From “Violence and Television” (1975):

The television set is a curiously ghostly medium: in our day, if we see ghosts or hear ghostly voices in the air, it means that somebody has left the television on. But the passive viewer’s whole world is equally spectral: he cannot distinguish fact from fiction either on the screen or off of it. He may see the most terrible event take place on the street before his eyes, but he will not lift a finger even to call the police. Nothing is really happening. This represents a central and frightening problem of violence itself: a zombie existence in which violence emerges as a desperate effort at identity. Marshall McLuhan’s phrase “the medium is the message” has been quoted so often, even at this conference, that it has lost all its meaning, if it ever had any. But another phrase of McLuhan’s is much more concrete: he speaks of a need for civil defence against media fallout, which exactly describes what I mean here. (CW 11, 162)

From Notes 54-5 (1976):

The McLuhan “hot & cool” classification of media relates them exclusively to emotional impact: there’s also a cognition element involved. Wonder if McLuhan is still buggered up by the warm emotion & cold intellect cliche. (CW 13, 213)

[W]e need a theory of verbal meaning which turns Aristotle inside out, starting with myth & metaphor as primary, & moving toward descriptive structures as specialized & secondary. The primary fiction that organizes the latter is causality: the correct form of McLuhan’s “linear” notion. Whitehead, SMW [Science and the Modern World]. (CW 13, 250)

“Logical” sequence is midway between subjective sequence, or association of ideas, and objective sequence, or progress of events. In any event hieratic language give a much greater emphasis to time–I suppose that’s partly what Marshall’s getting at. Causality, as I’ve often said, is built into the prose of language. (CW 13, 291)

Curious the number of times people have sold out to some silly cause because they couldn’t distinguish the demonic parody from the real thing. Heidegger has some remark in an essay about National Socialism being essentially the struggle against technology: he wanted so much to have peasants woo-wooing around the soil that he didn’t see that the Nazis were interested solely in demonic technology. Similarly with all the jerks who went for Stalinism, and disregarded all the evidence that Stalinism was the demonic opposite of Marx’s goal. On a very small scale, McLuhan contrasted a linear abstract spatial perception with a sensory and immediate spatial perception, and then spent the next fifteen years gradually realizing that the contrast of reading and television-watching he’d got it identified with was its demonic opposite. (CW 13, 304)

From Notes 54-13 (c. 1975-1982):

[William Morris’] sense of the “minor” or decorative arts as agents of revolution. What they did was, as above, to move backwards in time, from the brain to the hand. He got something Marshall McLuhan I think missed: he was preoccupied with the change from the linear to the simultaneous; but that’s still essentially passive in its orientation: there’s nothing to guarantee the activity of the learner. (CW 15, 326)

From the “Conclusion to the Second Edition of Literary History of Canada” (1976):

It is a typically Canadian irony that such a cataract [of Canadian literature] started pouring out of the presses just before Marshall McLuhan became the most famous of Canadian critics for saying that the book was finished. I doubt if one can find this in McLuhan, except by quoting him irresponsibly out of context, but it what he was widely believed to have said, and the assertion became very popular, as anything that sound anti-intellectual always does. (CW 12, 450)

[M]uch is said in this book and elsewhere about the religious drive in George Grant, in McLuhan, in myself. (CW 9, 461)

Mr. Lane refers to the zany quality of Marshall McLuhan’s style that has infuriated some people into calling him a humbug and a charlatan. (CW 12, 464)

From “Presidential Address at the MLA” (1976):

By a curious irony, the catholicity of the MLA creates a difficulty for its own periodical. Most learned journals are much narrower in range, and those who consult them know in advance the kind of thing they are looking for. In having to reflect the whole MLA conspectus, PMLA, according to the options I have heard, tends to become something of what Marshall McLuhan would call a medium of low definition, a collection of prize essays rather a journal with a specific shape. But it would, in my opinion, be a mistake to undervalue the attempt to reflect the scholarship in the modern languages as a total community, however large and miscellaneous. (CW 7, 486-7)

From “Notes for ‘Culture as Interpretation’” (1977):

McLuhan on tribalism is I suppose connected with my hunch about community in Canada, and I notice a book of not very interesting looking essays that talk about communitariansim. (CW 25, 202)

There is a hoary old wheeze about the United States having gone from the primitive to the decadent stage without an intervening period of civilization. There would, I think, be a bit more accuracy in the statement that Canada is a country that has gone from a pre-national to a post-national phase without ever really becoming a nation. It almost became one after the Second World War, in the Pearson-Diefenbaker era, but when Trudeau became Prime Minister and took Marshall McLuhan for one of his advisors we abandoned that phase. (CW 25, 203)

From “The Future Tense” (Broadcast 20 February 1977):

Narrator: As Northrop Frye says, Mr. McLuhan’s vision of apocalypse is worth thinking about. But there’s another side too.

Frye: The possibility of a smash is something that we would be foolish to dismiss. I think that our minds go in a kind of manic-depressive, up-and-down rhythm between feeling that we’re all going to be wiped out by the atomic bomb, which is the depressing one, and the feeling that we’re going to move into an Age of Aquarius where everything will be wonderful and lovely, which is the manic side. I don’t believe in either the manic peak or the depressive myth. I think that the human race somehow or other manages to stagger on between the two. (CW 24, 328-9)

From “Culture as Interpenetration” (1977):

As third-world nations began to emerge in Africa and Asia, Canada’s much more low-keyed nationalism became increasingly inaudible, like a lute in a brass band. . . When Trudeau became prime minister and adopted Marshall McLuhan as one of his advisors, Canada reverted to tribalism. (CW 12, 521-2)

From “The Education of Mike McManus” (Filmed 5 October 1977: interview by Mike McManus):

McManus: Marshall McManus, if I’ve understood him correctly, says or feels that the ultimate effect of the viewer of mass doses of television is one of apathy. This is not your conclusion, Dr. Frye. It’s more anarchy and violence.

Frye: I think it’s partly the conclusion. Apathy is a very important and central response. One can see that in the behaviour of people in the cities, where an act of violence can go on under their eyes and they just stand around with their hands in their pockets. That is the result of apathy. Marshall speaks of “civil defence against media fallout,” which I think is a very accurate phrase in that connection. (CW 24, 346)

From “Criticism, Language, and Education (1979):

The mythological universe that surrounds us includes all the really serious beliefs that we have. First of all, you get a level of utterly phony mythology, a level addressed by advertising and propaganda, that is expressed by all the cliches you can pick up on the streets and all the silly prejudices about minority groups that are a product of certain forms of class conditioning–the phony aspect of mythology has been quite extensively explored in our time by Roland Barthes, for example, in his book Mythologies, and by Marshall McLuhan in his book The Mechanical Bride. Behind that, however, are the real informing myths of our lives, of which we normally become conscious in some kind of crisis. In our society we do grow up with very powerful beliefs in things like democracy and equality of opportunity and so on, but it’s only in something like the Watergate crisis where we begin to realize how immensely powerful these myths are. (CW 25, 323)

From “Criticism as Education” (1979):

I spoke of various layers of our mythological envelope. The innermost layer is a phoney mythology, made of prejudice and gossip and the shallow and superficial reactions that inform so much casual conversation. This is the aspect of verbal mythology which is conveyed through advertising and propaganda. The distinction between reality and illusion is one of the most important activities that we use words for, and, as advertising and propaganda are designed deliberately to create an illusion, it follows that they form, in a sense, a kind of anti-language. Their effect on the modern world has been analyzed by, for example, Roland Barthes in Mythologies and by Marshall McLuhan in The Mechanical Bride. (CW 7, 533)

From “The Wisdom of the Reader” (25-26 May 1979: interview with Beppe Cottafavi):

Frye: [I]solated from nature and from the landscape, isolated from each other, Canadians have always had to fight their isolation, or at least understand it. And this explains, I think, their great interest in communications. The concept of communications is fundamental for historians and theorists like Harold Innis, George Grant, and Marshall McLuhan. The concept of communications is also basic to my own work. Literature, in fact, is an indirect form of communication. (CW 24, 457)

1980s

From “Introduction to the Second Volume of Harold Innis’s A History of Communications” (c. 1980s):

Marshall McLuhan, we also saw, developed, partly through his study of Innis, the intuition that the entire history of writing had not only an origin in the silent communication of trade, but a conclusion in a gigantic expansion of human consciousness. He identified this latter with the electronic media, and used the metaphorical contrast of “linear” and “simultaneous” to express what he felt was coming. McLuhan is later than Innis, but even his books appeared before the invention of the microprocessor, and it now looks as though the road to the future of communications runs through computer science. Eventually, no doubt, we shall have machines that stand in the same relation to ordinary human brains that jet planes to to ordinary human feet. On the way there will be bitter struggles as entrenched authority grimly hangs on to its prerogatives and as pressure groups attempt to seize them. But even now, before we have entered that period, we can see that Innis’s work is prophetic and not merely a scholarly vision of the past. (CW 10, 306)

From “Canadian Energy: Dialogues on Creativity” (Conducted 3 and 16 April 1980):

Frye: As long as there are two lobes of the brain, there are going to be the two possibilities of Western and Oriental thinking. And I think that everybody tries to produce what Marshall McLuhan called a “counter-environment.” That is, you set yourself in opposition to the kind of mass tendencies which the media set up. That’s what’s so important about the humanities in the university; there is always something of Mark Hopkins and the log. There’s something of a personal dialogue between one human being and another. And the fact that this dialogue is being carried out in the teeth of all the mass emotion techniques of the electronic media is a very important side of the humanities. I suspect that no teaching is worth doing unless it has a militant quality in it. (CW 24, 488)

From “Across the River and out of the Trees” (1980):

Marshall McLuhan, a literary critic interested originally in Elizabethan rhetoric and its expression in both oral and written forms, followed up other issues connected with the technology of communication, some of them leads from Innis. His relation to the public was the opposite of Innis’s: he was caught up in the manic-depressive roller-coaster of the news media, so that he was hysterically celebrated in the 1960s and unreasonably neglected thereafter. It is likely that the theory of communications will be the aspect of the great critical pot-pourri of our time which will particularly interest Canadians, and to which they will make their most distinctive contribution. So it is perhaps time for a sympathetic rereading of The Gutenberg Galaxy and Understanding Media and a reabsorption of McLuhan’s influence, though no adequate treatment of this topic can be attempted here.

I have often noted that many nineteenth century writers in Canada, especially poets, spoke of what could be called, paraphrasing the title of Francis Sparshott’s remarkable poem, the rhetoric of the divided voice. Up above was vigor and optimism and buoyancy and all the other qualities of life in a new land with lots of natural resources to exploit; underneath were lonely, bitter, brooding visions of cruelty without and despair within. The division in tone is still in Pratt, in a different way, and can even be traced in later writers, such as Layton, though the context naturally changes. It is by no means confined to Canada, as a reading of Whitman would show, but is traditional here. McLuhan put a similar split rhetoric into an international context. On top was a breezy and self-assured butterslide theory of Western history, derived probably from a Chestertonian religious orientation, according to which medieval culture had preserved a balanced way of life that employed all the senses, depended on personal contact, and live with “tribal,” or small community units. Since then we skittered down a slope into increasing speculation (McLuhan defines the specialist as the man who never makes a minor mistake on his way to a major fallacy), a self-hypnotism from concentrating on the visual stimuli of print and mathematics, a dividing and subdividing of life into separate “problems,” and an obsession with a linear advance also fostered by print and numbers. The electronic media, properly understood and manipulated, could reverse the direction of all this. Below was a horrifying vision of a global village, at once completely centralized and completely decentralized, with all its senses assailed at once, in a state of terror and anxiety at once stagnant and chaotic, equally a tyranny and an anarchy. His phrase “defence against media fallout” indicated this direction in his thought.

In the 1960s both the anti-intellectuals, who wanted to hear that they had only to disregard books and watch television to get with it, and the “activists,” pursuing terror for its own sake, found much to misunderstand in McLuhan. Many of his theses involved research in linguistics, anthropology, sensory psychology, and economics which has still to be done or even established in those fields, and his recurring tendency to determinism involved him in prophecies not born out by events. Media may be hot or cool. But McLuhan raised questions that are deeply involved in any survey of contemporary culture, and in any attempt to define the boundaries of the emerging theory of society that I call “criticism” in its larger context. (CW 12, 559-60)

From “Marshall McLuhan” (Broadcast 4 January 1981—this CBC radio interview was broadcast five days after McLuhan’s death on 31 December 1980):

Interviewer: Professor McLuhan’s great contemporary at the university, Northrop Frye, says that McLuhan’s background enabled him to achieve his insights.

Frye: He as a literary critic and that meant that he looked at the form of what was in front of him instead of the content. And so instead of issuing platitudes about what was being said on television he looked at what the media were actually doing to people’s eyes and ears. He had a gift of epigrammatic encapsulating that made some of the things he said extremely memorable.

[On the decline of McLuhan’s influence in the 1970s]

[H]e got on the manic-depressive roller-coaster of the news media and that meant he went away to the skies like a rocket and then came down like a stick. But he himself and what he said and thought had nothing to do with that. That’s what the news media do to people if you get caught up in their machinery. (CW 24, 510-11)

From “A Fearful Symmetry” (Conducted 15 April 1981: interview with Donald G. Bastian):

Bastian: When people think of Canadian scholars, they invariably put two people together as prime examples: the late Marshall McLuhan and you. How well did you know McLuhan?

Frye: I knew Marshall reasonably well. We were colleagues in the same department. Later, of course, we both became extremely busy in different lines, so we saw less of each other than we had.

Bastian: Have his views been well understood?

Frye: Well, yes and no. What he said was perhaps praised too much for the wrong reasons in the 1960s. And I think he himself realized as well as anybody that they were the wrong reasons. So his intellectual career seems to me to be curiously unfinished this way. He wrote two remarkable books: The Gutenberg Galaxy and Understanding Media. Everything he wrote after that seems to have been in collaboration with other people and he got increasingly tentative, so that he wouldn’t even defend a position if it were criticized. He’s say, “Well, that’s just a probe, something to think about.” In a way that came to be a substitute for the very serious work I think he could have gone on to do.

Bastian: What do you think his lasting influence will be?

Frye: I suppose his recognition of the fact that the electronic media were bringing in a form of comprehension which was not new, because it was a recreation of things that have always been here, but was new in relation to the domination of print and mathematics. The whole business of being able to see the symbolic importance of things like the electric light, and the occasional insight, such as the way the telephone turned the street-walker into the call girl—that kind of sharp, detailed observation was very unusual. I rather wish he’d carried his academic interests more along with his interest in the contemporary scene, that he’d added his observation of the contemporary scene as an extension of his academic work. (CW 24, 522-3)

From “Medium and Message” (Recorded 1 May 1981: interview with Russell Davies):

Frye: I rather wish that Marshall had come to terms with the linear nature of the book because I think he would have been a much more permanent influence if he had done. What he said about the linear quality and the self-hypnotizing power of the eye in written books and mathematics was, I think, with all due respect to him, a half truth. There’s another side to the printed text, and that’s its uniformity, the fact that it always says the same thing, no matter how often you open it. That seems to me an equally obvious aspect of it. For example, when it came in in the sixteenth century, it had a very close association with magic. You can see that in Shakespeare’s Tempest when Caliban says of Prospero, “Burn but his books, because without them he is just as big a fool as I am.” And that capacity for the printed word to create a kind of instant hallucination is distinct from the merely remembered thing of oral culture. There are so many aspects of the written word which were there right in front of him and which he knew about, and I rather wish he had incorporated them. It was really the G.K. Chesterton butterslide: the notion that everything was unified in the Middle Ages and that we have been splitting and specializing ever since.

What I regret in the distinction of hot and cool media is the tendency to determinism in this thinking, which made him assume that a nation would turn hot or cool as its prevailing media were hot or cool. And he might perhaps have noticed the fact that he lived in a very cool country where all the tempers are cool and consequently all the media are cool. . .

I don’t think academics ought to get on this manic-depressive roller-coaster of publicity. There are just not built for it; they are built for much longer and more leisurely rhythms. And I think he was a little confused by being blown up so much in the 1960s and even more confused by being neglected in the 1970s. . . (CW 24, 536-7)

From “The Double Mirror” (1981):

[M]etaphor was made for man and not man for metaphor; or as my late and much beloved colleague used to say, man’s reach should exceed his grasp, or what’s a metaphor? (CW 4, 90)

From “Criticism and Environment” (1981):

In our world the control of communications is connected with what is called advertising in some contexts and propaganda in others, depending on the economic context involved. A somewhat unlikely disciple of Innes, Marshall McLuhan, published his first and I think his best book, The Mechanical Bride, in 1951. This is a study of a psychological appeals and responses in advertising. As its title indicates, it seizes on that curious identification of the erotic and the mechanical that seems so central to the sensibility of our age: Eros and Thanatos locked together in a peculiarly twentieth-century embrace. My copy of this book classifies it as “sociology,” but McLuhan was a literary critic who remarks in his introduction that it is high time for the techniques of criticism, in literature and the other arts, to be applied to the analysis of society.