McLuhan on the influence of Wyndham Lewis on his work:

Good heavens, that’s where I got it! (…) Lewis was the person who showed me that the man-made environment was a teaching machine — a programmed teaching machine. But earlier, you see, the symbolists had discovered that the [individual] work of art was a programmed teaching machine. It’s a mechanism for shaping sensibility. Well, Lewis simply extended this private art activity to the corporate activity of the whole society in [its] making environments that basically were artifacts, or works of art, and that acted as teaching machines on the whole population. (Lewis in St Louis, 1967)1

According to Lewis, “The artist is engaged in writing a detailed history of the future because he is the only person who lives in the present.” And in his own writing Lewis foresaw many of the problems of today. (…) Giovanelli and I (…) were eager to discuss his own work with him and especially his more controversial “pamphlets” like The Doom of Youth, Time and Western Man, and The Art of Being Ruled. (…) He was utterly beyond the reach of the ordinary political, social, artistic interests of the day. In fact, it is only since the disappearance of the vast bulk of his contemporaries from the scene that his image has assumed its true dimensions in the history of art and letters. (…) He was tirelessly alert to all sorts of contemporary developments in the popular media which I have ever since found a world of delight. (…) Even in the ’20s, as Sheila Watson expresses it, he observed the intrusion of the mechanical foot into the electric desert. Is it any wonder that his analysis of the political, domestic, and social effects of the new technological environments had a great deal to do with directing my attention to these events? (My Friend Wyndham Lewis, 1969)

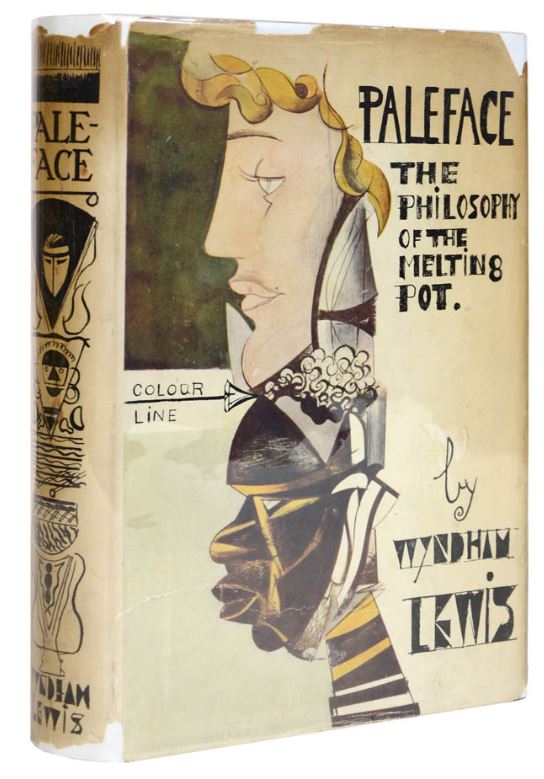

Below are excerpts from the ‘Introduction’ to the second part of Lewis’ 19292 book Paleface. Also included here are references to The Monthly Criterion from July 1927 which featured an essay from Lewis entitled ‘The Values of the Doctrine Behind “Subjective” Art’. This was the original appearance of most of Lewis’ ‘Introduction’ — one that McLuhan is known to have seen.3

These essays do not come under the head of ‘literary criticism ’ They are written purely as investigations into contemporary states of mind, as these are displayed for us by imaginative writers pretending to give us a picture of current life ‘as it is lived,’ but who in fact give us much more a picture of life as, according to them, it should be lived. In the process they slip in, or thrust in, an entire philosophy, which they derive from more theoretic fields, and which is usually not at all the philosophy of the sort of people they portray. The whole of Paleface, in fact, deals with and is intended to set in relief the automatic processes by which the artist or the writer (a novelist or a poet) obtains his formularies: to show how the formulas for his progress are issued to him, how he gets them by post, and then applies them. (Paleface 97-98) (Criterion 4)

According to present arrangements, in the presence of nature the artist or writer is almost always apriorist, we suggest. Further, he tends to lose his powers of observation (which, through reliance upon external nature, in the classical ages gave him freedom) altogether. (…) So he takes his nature, in practice, from theoretic fields, and resigns himself to see only what conforms to his syllabus of patterns. He deals with the raw life, thinks he sees arabesques in it ; but in fact the arabesques that he sees (…) emanate from his theoretic borrowing, he has put them there. It is a nature-for-technical-purposes.

(Paleface 98) (Criterion 4)

Scarcely any longer can he be said to control or be even in touch with the raw at all, that is the same as saying he is not in touch with nature: he rather dredges and excavates things that are not objects of direct perception, with a ‘science’ he has borrowed (…) observes only according to a ‘system’4 of opinion which hides from him any but a highly selective reality. (Paleface 98) (Criterion 4)

‘Life’ is not-knowing: it is [therefore] the surprise packet: so (…) if nature can be so arranged as to yield him as it were a system of surprises, the artist will scarcely take the trouble to look behind them, to detect the principle of their occurrence (…) He automatically applies the accepted formula to nature; the corresponding accident manifests itself, like a djinn, always with an imposing clatter (since it is a highly selective ‘accident’ that understands its part): and the artist is perfectly satisfied that nature has spoken. He does not see at all that ‘nature’ is no longer there. (Paleface 99) (Criterion 5)

If I could surprise anybody into examining with a purged and renewed sense what is taken so much for granted, namely our ‘subjectivity’ — though who or what is the subject or Subject? — I should have justified any method [of attempted communication] whatever. (Paleface 99) (Criterion 5)

Oh it is a wild life that we live (…) between one apocalypse and another!5 (Paleface 100) (Criterion 6)

In a word, we have lost our sense of reality. So we return to the central problem of our ‘subjectivity,’ which is what we have in the place of our lost sense…

(Paleface 100) (Criterion 6)

Elsewhere I have described this in its great lines as the transition from a public to a private way of thinking and feeling. The great industrial machine has removed from the individual life all responsibility.6 (…) It is evidently in these conditions that you must look for the solid ground of our ‘subjective’ fashions. The obvious historic analogy is to be found in the Greek political decadence. Stoic and other philosophies set out to provide the individual with a complete substitute for the great public and civic ideal of the happiest days of Greek freedom: with their [Stoic and other then contemporary philosophical] thought we are quite at home. (Paleface 100-101) (Criterion 6)

There is not much resemblance, outwardly, between the pulverization by one central power, such as that of Rome, and the pulverization of our social and intellectual life that is being effected by general industrial conditions all over the world. But there is, in the nature of things, the same oppressive removal of all personal outlet (…) in a great public life of individual enterprise: and (…) at the same time, through the agency of Science, all our standards of existence have been discredited. (Paleface 101-102) (Criterion 7)

[Bertrand Russell] “The kind of difference that Newton has made to the world is more easily appreciated where a Newtonian civilization is brought into sharp contrast with a pre-scientific culture, as for example, in modern China. The ferment in that country is the inevitable outcome of the arrival of Newton upon its shores. (…) If Newton had never lived, the civilization of China would have remained undisturbed, and I suggest that we ourselves should be little different from what we were in the middle of the eighteenth century.” (Radio Times, April 8th. 1928.)

[Lewis] If you substitute Science for Newton (…) that explains our condition. We have been thrown back wholesale from the external, the public world, by the successive waves of the ‘Newtonian’ innovation, and been driven down into our primitive private mental caves, of the unconscious and the primitive. We are the cave-men of the new mental wilderness. That is the description, and the history of our particular ‘subjectivity’.

(Paleface 102–103) (Criterion 8)

In the arts of formal expression, a ‘dark night of the soul’ is settling down. A kind of mental language is in process of invention, flouting and overriding the larynx and the tongue. Yet an art that is ‘subjective’ and can look to no common factors of knowledge or feeling, and lean on no tradition, is exposed to the necessity, either7 of instructing itself far more profoundly as to the origins of its impulses and the nature and history of the formulas with which it works; or else it is committed to becoming a zealous parrot of systems and judgments that reach it from the unknown. In the latter case in effect what it does is to bestow authority upon a hypothetic something or someone it has never seen, and would be at a loss to describe (since in the ‘subjective’ there is no common and visible nature), and progressively to surrender its faculty of observation, and so sever itself from the external field of immediate truth or belief — for the only meaning of ‘nature’ is a nature possessed in common. And that is what now has happened to many artists: they pretend to be their own authority, but they are not even that. It would not be easy to exaggerate the naivete with which the average artist or writer to-day, deprived of all central authority, body of knowledge, tradition, or commonly accepted system of nature, accepts what he receives in place of those things.

(Paleface 103-104) (Criterion 8)

It is astonishing how in all the heated dogmatical arguments, you will never find them calling in question the very basis upon which the ‘movement’ they are advocating rests. They are never so ‘radical’ as that. (…) They have not the least consciousness (…) of the many alternatives open to them. The authority of fashion is absolute in such cases: whatever has by some means introduced itself and gamed a wide crowd-acceptance (…) is, itself, unassailable. Its application, only, presents alternatives. The world of fashion for them is as solid and unquestionable as that large stone, against which Johnson hit his foot, to confute the Bishop of Cloyne. For them the time-world has become an absolute, as it has for the philosopher in the background, feeding them with a hollow assurance.

(Paleface 104-105) (Criterion 9)

a herd of happy and ignorant technicians entranced, not with ‘mind’, but with ‘subjectivity’. (Paleface 105) (Criterion 10)

The kind of screen that is being built up between the reality and us, the ‘dark night of the soul’ into which each individual is relapsing, the intellectual shoddiness of so much of the thought responsible for the artist’s reality, or ‘nature’ today, all these things seem to point to the desirability of a new and if necessary shattering criticism of ‘modernity’ as it stands at present. (Paleface 106) (Criterion 10)

It is an unenterprising thought indeed that would accept all that the ‘Newtonian’ civilization of science has thrust upon our unhappy world, simply because it once had been different from something else, and promised ‘progress’ though no advantage so far has been seen to ensue from its propagation for any of us, except that the last vestiges of a few superb civilizations are being stamped out, and a million sheep’s-heads, in London, can sit and listen to the distant bellowing of Mussolini; or (…) to the [nearby] bellowing of Dame Clara Butt.8 It is too much to ask us to accept these privileges as substitutes for the art of Sung [China] or the philosophy of Greece. (Paleface 106) (Criterion 11)

Most dogmatically ‘subjective’, telling-from-the-inside, fashionable method — whatever else it may be (…) — is ultimately discovered to be bad philosophy — that is to say, it takes its orders from second rate philosophic dogma. Can art that is a reflection of bad philosophy be good art? (Paleface 107) (Criterion 12)

But if, politically and socially, men are today fated to a ‘subjective’ role, and driven inside their private, mental caves, how can art be anything but ‘subjective’ too? Is externality of any sort possible for us? Are we not of necessity confined to a mental world of the subconscious, in which we naturally sink back to a more primitive level (…)? Our lives cannot be described in terms of action — externally that is — because we never truly act. We have no common world into which we [might] project ourselves (…) To those [political and social] questions we (…) in due course would be led: but what here I have been trying to show is that first of all much more attention should be given to the intellectual principles that are behind the work of art: that to sustain the pretensions of a considerable innovation a work must be surer than it usually is to-day of its formal parentage: that nothing that is unsatisfactory in the result should be passed over, but should be asked to account for itself in the abstract terms that are behind its phenomenal face. And I have suggested that many subjective fashions, not plastically or formally very satisfactory, would become completely discredited if it were clearly explained upon what flimsy theories they are in fact built: what bad philosophy, in short, has almost everywhere been responsible for the bad art.

(Paleface 108-109) (Criterion 12)

My main object in Paleface has been to place in the hands of the readers of imaginative literature, and also of that very considerable literature directed to popularizing scientific and philosophic notions, in language as clear and direct as possible, a sort of key; so that, with its aid, they may be able to read any work of art presented to them, and, resisting the skillful blandishments of the fictionist (…) understand the ideologic or philosophical basis of these confusing entertainments, where so many false ideas change hands or change heads. As it is, the popularizer is generally approached with the eyes firmly shut and the mouth wide open. [As a result] the fiction (…) takes with it the authority of life — people live it, as it were, as they read: so it is able to pass off as true almost anything.9 The often very elaborate philosophy expressed in this sensational form very often not only misrepresents the empirical reality, but misstates the truth. (Paleface 109) (Not in the Criterion essay)

- Flexidisk recording in artscanada No. 114, November 1967. For the recording itself, images and discussion, see Andrew McLuhan’s post:

https://inscriptorium.wordpress.com/2011/01/12/mechanisms-for-shaping-sensibility/. ↩ - Much of Paleface was written and published in 1927. As described in this post, much of the ‘Introduction’ to its second part appeared in The Monthly Criterion from July 1927. Nearly all of the rest of that second part appeared in October that same year in Lewis’ The Enemy Number 2. ↩

- In his unpublished manuscript, ‘The Little Epic’, dating to the middle or late 1950s, McLuhan cites a passage from the ‘Introduction’ to Part ii of Paleface, but in doing so he references, not Paleface from 1929, but the earlier appearance of most of that ‘Introduction’ in T.S. Eliot’s magazine, The Monthly Criterion, from July 1927. Here is the citation: “We have been thrown back wholesale from the external, the public, world, by the successive waves of the ‘Newtonian’ innovation, and been driven down into our primitive private mental caves, of the Unconscious and the primitive. We are the cave-men of the new mental wilderness. That is the description, and the history, of our particular ‘subjectivity’. In the arts of formal expression, a ‘dark night of the soul’ is settling down. A kind of mental language is in process of invention, flouting and overriding the larynx and the tongue.” (Paleface 103) (Criterion 8) An echo of this passage appears in McLuhan’s 1969 ‘My Friend Wyndham Lewis’: “he was pleased to quote Eliot’s observation in The Egoist (September, 1918) that ‘in the work of Mr. Lewis we recognize the thought of the modern and the energy of the cave man’.” McLuhan comments further in his ‘Little Epic’ manuscript: “Wyndham Lewis is no friend or admirer of the various art forms which we are reviewing here under the head of ‘little epic’. But he is an invaluable guide to all that these forms mean.” ↩

- Although Lewis also uses science and system in other senses than these, he does not mark his depreciative use of them here with scare quotes. They have been added to mark their ambiguity in his work. ↩

- Elsewhere in Paleface commenting on “a herd (…) driven madly hither and thither in gigantic wars that have at length become completely meaningless”: “If this apocalyptic picture sounds to your ears sensational or far-fetched, I can only say that you forget very quickly what was called at the time (= WW1) ‘Armageddon’.” (26) ↩

- In ‘Lemuel in Lilliput’ (1944), McLuhan cites Lewis from The Art of Being Ruled (142): “The first object of a person with a desire to be free, and yet possessing none of the means (…) such as money, conspicuous ability, or power to obtain freedom, is to avoid responsibility. Absence of responsibility (…) is what men most desire for themselves.” ↩

- Instead of ‘either’, Lewis has ‘first of all’. ↩

- Clara Butt: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clara_Butt. ↩

- Compare McLuhan in Laws of Media (16) half a century later: “Under the spell of mimesis the knower (hearer of a recitation) loses all relation to his merely present persona (…) and is transformed by and into what he perceives. It is not simply a matter of representation but rather one of putting on a completely new mode of being, whereby all possibility of objectivity and detachment of figure from ground is discarded. Eric Havelock devotes a considerable portion of Preface to Plato to this problem.” ↩

- The medium is the message. McLuhan in ‘Lemuel in Lilliput’: “It is therefore, politically and humanly speaking, a matter of the utmost concern for us to know from what sources and by what means the rulers of the modern world determine what they will do next. How do they determine the ends for which, as means, they employ the vast machines of government, education, and amusement?” The phrase “rulers of the world” is used by Lewis in Paleface 88. ↩