In the first of his published letters, from February 19, 1931 to his mother, McLuhan records his introduction to G.B. Shaw:

I was initiated to the writings of Mr Bernard Shaw last evening when we attended a very admirable performance of Pygmalion presented by the University. (…) I was very agreeably surprised. [Shaw] has looked at life with a very penetrating if a somewhat disapproving eye. I should think that he deserves one of the highest places among English dramatists, after Shakespeare. (…) Shaw has studied life and reduced his observations to pithy and valuable aphorisms (…) I shall certainly get thru Shaw at the earliest opportunity. (Letters 9)

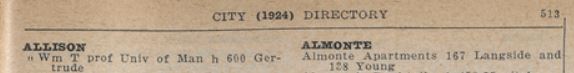

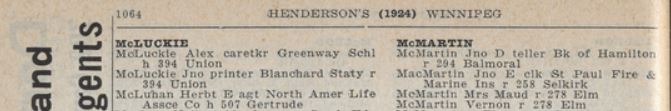

Five months later that same year, on July 18, just before McLuhan’s 20th birthday on July 21, a lengthy appreciation of Shaw appeared in the The Manitoba Free Press.1 A clipping of the article was found in McLuhan’s copy of Shaw’s Androcles and the Lion, Overruled, [&] Pygmalion,2 which, in turn, is now preserved among his books donated by the McLuhan family to the Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto.3

No author is identified. But there are multiple reasons to suspect that this was the work of McLuhan4 and, therefore, his first work to appear outside of University of Manitoba student publications:

- The article appeared half a year after he had written to his mother that he would “certainly get thru Shaw at the earliest opportunity”.

- The clipping was preserved by McLuhan for 50 years.

- It was preserved in his copy of Pygmalion, the very play which introduced him to Shaw in the first place.

- In his library at Fisher, there are more books authored by Shaw than any other author, many of which are annotated and at least one ‘heavily annotated’.

- Many phrases in the article have the McLuhan ring to them: “a sense of grievance”, “draper’s assistants, who were able to endure the drab realities of their days only by dwelling in preposterous unreality at night”, “the underlying will that governs ideals, the unconscious desires that urge them into being”, “nature does not dance to moralist-made tunes”;5 “the overwhelming sanity with which Mr. Shaw intimidates us”, “how to blast this disorder from the earth has become Mr. Shaw’s chief preoccupation”, Shaw “divides his personality into a hundred appallingly articulate [forms] so that the entire stage of our time is populated with bits and multiples and off-shoots of Shaw”, “the whole point and substance of Shaw’s teaching are that he is content, that he is in favor of this whirlgig process that will inevitably bring him to negation”, “not egotism at all but an unusually superior and bracing kind of honesty”, “a constitutional inability to look below the surface”, “the whole tenor of his plays is impatience with us because we never think; but he can give us a premonition of thinking. He drives the comfortable fogs out of our minds as the prophets of old drove demons out of the possessed, not with rites and incantations, but with railleries and caustic jesting”.

- The article mentions Chesterton which very few in Winnipeg aside from McLuhan would have done at the time (or any other time).

- Shaw is described as being “against schools as they are (his education was ‘interrupted’ by ten years’ schooling)”. This was a frequent topic of McLuhan in Winnipeg.6

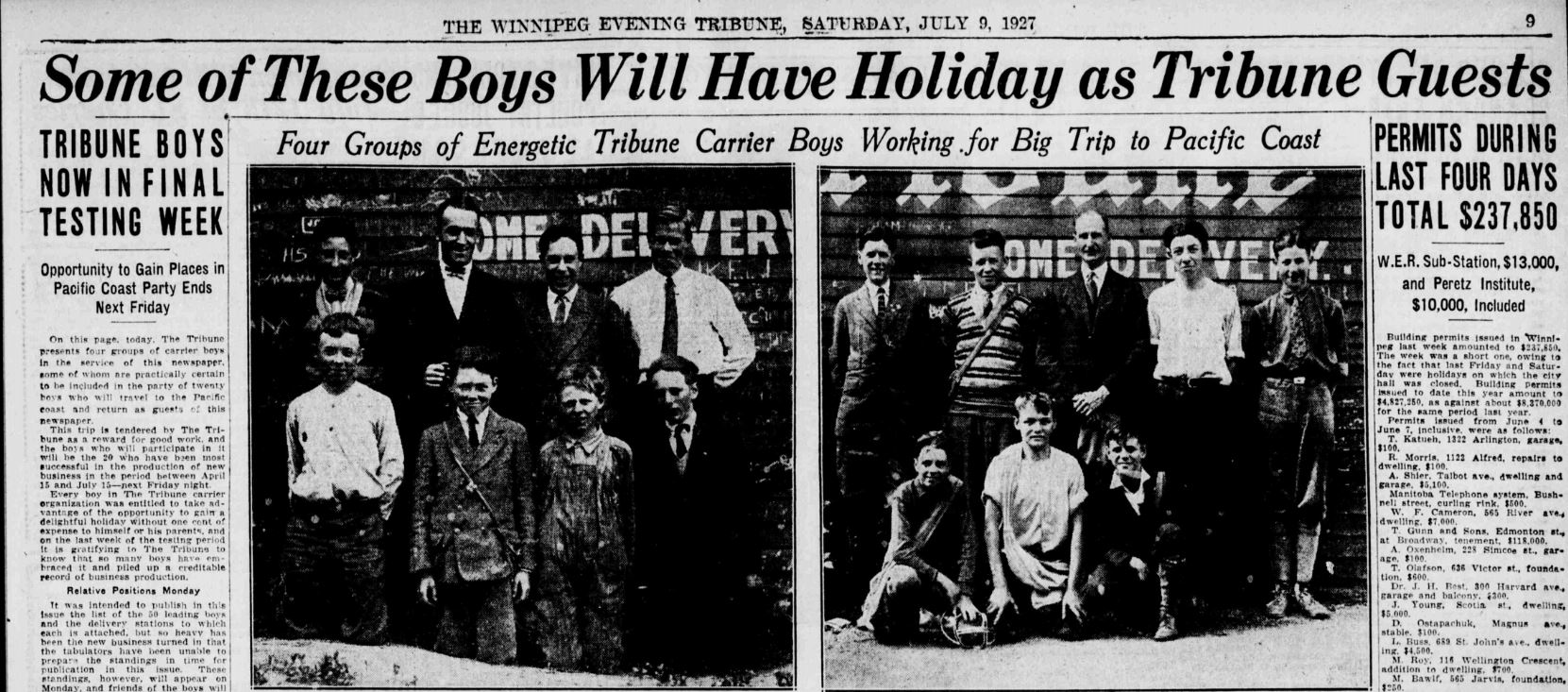

- The ‘Interesting Book Notes’ on the same page includes a short review of The Spirit of British Policy. The reviewer focuses on Germany. McLuhan wrote a series of articles in the UM student paper, The Manitoban, on Germany.7

- In a letter to his family from Cambridge from September 5, 1935, McLuhan wrote that he was “going to write 2 or 3 articles for The Free Press.” (Letters 76)

- That McLuhan had some kind of relationship with J.W. Dafoe,

the longtime editor of The Free Press, may be indicated by the fact that in 1936 McLuhan’s first paper for the Dalhousie Review (‘Chesterton: A Practical Mystic’) and Dafoe’s only paper ever to appear there (‘Canada’s Interest in the World Crisis’) were published in the same issue:

the longtime editor of The Free Press, may be indicated by the fact that in 1936 McLuhan’s first paper for the Dalhousie Review (‘Chesterton: A Practical Mystic’) and Dafoe’s only paper ever to appear there (‘Canada’s Interest in the World Crisis’) were published in the same issue:

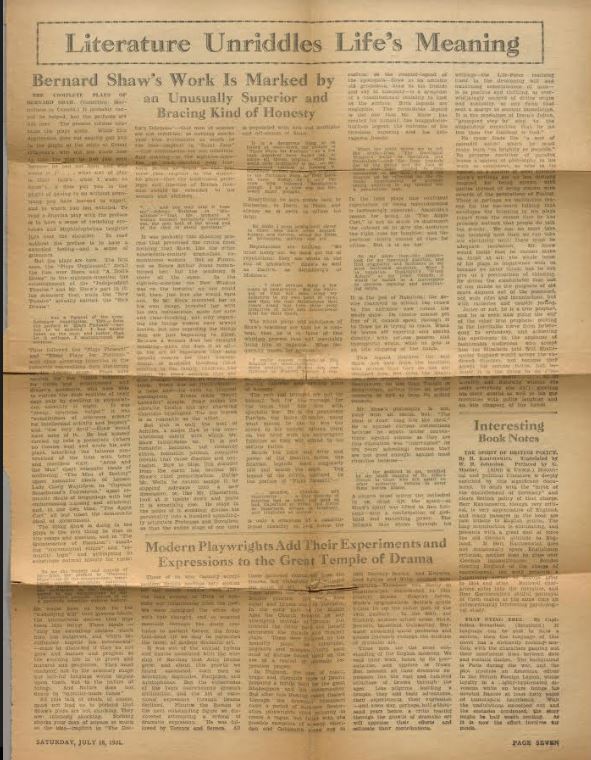

Here is the article on Shaw from The Free Press, Saturday, July 18, 1931, p 7:

Literature Unriddles Life’s Meaning

Bernard Shaw’s Work Is Marked by an Unusually Superior and Bracing Kind of Honesty

[Review of] The Complete Plays Of Bernard Shaw (Constable: Macmillans in Canada.)

It probably cannot be helped, but [Shaw’s] prefaces are not here. The present volume contains the plays alone. While this deprivation does not exactly put you in the plight of the critic at Count O’Dowda’s [in Fanny’s First Play, by Shaw], who did not know how to take the play he had just seen because he had not been told who wrote it (“what sort of play is this? that’s what I want to know”), it does put you in the plight of having to do without something you have learned to expect, and to which you feel entitled. To read a Shavian play with the preface is to have a sense of twitching eyebrows and Mephistophelian laughter just over the shoulder. To read without the preface is to have a swindled feeling — and a sense of grievance.

But the plays are here. The first ones, the Plays Unpleasant, recall the fuss over Ibsen and A Doll’s House in the eighteen-nineties; the establishment of the “Independent Theatre,” and Mr. Shaw’s part in it; his discovery that, while the “New Theatre” actually existed, the “New Drama” was a figment of the revolutionary imagination. “This (from the preface to Plays Pleasant) was not to be endured. I had rashly taken up the case; and rather than let it collapse, I manufactured the evidence.”

Then followed the Plays Pleasant and Three Plays for Puritans, with their alarming inversion of the romantic conventions then cluttering the London stage. Plays were written for the “timid majority”, for clerks and seamstresses and draper’s assistants, who were able to endure the drab realities of their days only by dwelling in preposterous unreality at night.8 It was “cheap, spurious, vulgar,” it was “substitution of sensuous ecstacy for intellectual activity and honesty” and “the very devil” — Shaw would have none of it. He had himself carried up into a mountain (where no theatre was) and wrote his own plays, attacking the fatuous conventions of the time with tonic and merciless vigor. Arms and the Man upset romantic ideals of soldiering: The Man of Destiny upset romantic ideals of heroes; Lady Cicely Waynflete, in Captain Brassbound’s Conversion, upset romantic ideals of brigandage with her embarrassing nursing and stitching; and, in our own time, The Apple Cart all but upset the democratic ideal of government.

The thing Shaw is doing in the plays is the very thing he does in the essays and treatises, and in The Quintessence of Ibsenism: assailing “conventional ethics” and “romantic logic” and attempting to substitute natural history for them: “To me the tragedy and comedy of life (from the preface to Pleasant Plays) lie in the consequences, sometimes terrible, sometimes ludicrous, of our persistent attempts to found our institutions on the ideals suggested to our imaginations by our half-satisfied passions, instead of on a genuinely scientific natural history.”

He would have us look for the “underlying will” that governs ideals, the unconscious desires that urge them into being. These ideals “only the swaddling clothes which man has outgrown, and which insufferably impede his movements” — must be discarded if they do not grow and mature and progress as the evolving life in us grows and matures and progresses. They must conform, not to the arbitrary shape our self-full longings would impose upon them, but to the nature of things. And Nature does not dance to “moralist-made tunes.”

All this talk of ideals, of course, must not lead us to pretend that Shaw’s plays are not shocking. They are: intensely shocking. Nothing shocks your man of science so much as the idea — implicit in The Doctor’s Dilemma — that men of science are not infallible; as nothing shocks your true ecclesiastic so much as the idea — implicit in Saint Joan — that ecclesiastics are not infallible. And nothing in the eighteen-nineties, at least, shocked your freeborn Briton so much as the perverse idea — implicit in the domestic plays — that the traditional privileges and liberties of British freedom should be extended to his women and children: “and you may take it from me” (Johnny Tarleton in Misalliance) “that the moment a woman becomes pecuniarly independent, she gets hold of the wrong end of the stick in moral questions.”

It was probably this shocking process that prevented the critics from noticing that Shaw, like the other nineteenth-century dramatists, romanticizes woman. Not as [Arthur Wing] Pinero, not as Henry Arthur Jones romanticized her;9 but the tendency is there all the same. In the eighteen-nineties the New Woman was on the horizon: no one could tell, then, just how she would turn out. So Mr. Shaw recreated her in his own image, invested her with his own omniscience, made her sane and clear-thinking, not only regarding the things women have always known, but also regarding the things men are just beginning to know. Because a woman does her straight thinking — when she does it at all — in the arc of experience that men usually reserve for their conventional, or muddled thinking (that relating to the family, children, the home). Mr. Shaw assumes that she does straight thinking all around the circle. There was no justification — is none now — for such an illogical assumption. Pinero made “Sweet Lavender” simple. Shaw makes his adorable Cicelys and gay charming Candidas intelligent. The one legend is as romantic as the other.

But this is only the heel of Achilles, a single flaw in the overwhelming sanity with which Mr. Shaw intimidates us. It is not romantic heroines, but romantic ethics, romantic politics, romantic morals, that cause disorder and confusion. How to blast this disorder from the earth has become Mr. Shaw’s chief preoccupation. Unlike Mr. Wells, he cannot escape it by slipping sideways into a new dimension, or, like Mr. Chesterton, look at it upside down and prove it is something else. He stays in the midst of it, scolding; divides his personality into a hundred appallingly articulate Proteuses10 and Duvallets11, so that the entire stage of our time is populated with bits and multiples and off-shoots of Shaw:12 “It is a dangerous thing to be hailed at once (from the preface to Three Plays for Puritans) as a few rash admirers have hailed me, as above all things original; what the world calls originality is only an unaccustomed method of tickling it. Meyerbeer seemed prodigiously original to the Parisians when he first burst on them. Today, he is only the crow who followed Beethoven’s plough. I am a crow who has followed many ploughs.”

Everything he says points back to Nietzsche, to Ibsen, to Plato, and always he is swift to affirm his debt: “No doubt I seem prodigiously clever to those who have never hopped, hungry and curious across the fields of philosophy, politics and art.”

Reputations are nothing. “We must hurry on: we must get rid of reputations: they are weeds in the soil of ignorance.” Shaw’s as well as Ibsen’s, as Strindberg’s or Moliere’s: “I shall perhaps enjoy a few years of immortality. But the whirlgig of time will soon bring my audiences to my own point of view: and then the next Shakespeare that comes along will turn these petty tentatives of mine into masterpieces final for their epoch.”

The whole point and substance of Shaw’s teaching are that he is content, that he is in favor of this whirlgig process that will inevitably bring him to negation. What frequently passes for egotism — “I really cannot respond to this demand for mock-modesty. I write prefaces as Dryden did, and treatises as Wagner, because I can.” — is not egotism at all but an usually superior and bracing kind of honesty.

The cart and trumpet are not for himself, but for his message, for the vision that fills him with apostolic fire. He is the passionate Puritan, the fierce Crusader, using what means he can to win the crowd to his beliefs; hitting them on the head with his extravagant fooleries so they will attend to his serious faiths.

Beside the force and drive and power of the Shavian faiths, the Shavian legends seem singularly idle and beside the mark. The legend of the critics, outlined in the preface of “Plays Pleasant” — “paradoxy, cynicism, and eccentricity, trite formula of treating bad as good and good as bad, important as trivial, and trivial as important, serious as laughable, and laughable as serious” — is only a symptom of a constitutional inability to look below the surface; [it is] the counter-legend of the apologists — Shaw as an amiable and old gentleman, kind to his friends and shy in company. Both legends are negligible. The formidable legend is the one that Mr. Shaw has created for himself: the braggadocio-buffoon legend, the outcome of his frivolous capering and his outrageous boasts: “When the spirit drives me to tell the truth (from The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism and Capitalism) and the flesh reminds me of the police and the fate of those who have yielded to that temptation in the past, I screw my courage up by reflecting on the extreme improbability of anybody seeing anything in my treatise but a paradoxical joke.”

In the later plays this confident expectation of being misunderstood is increasingly apparent. Amanda’s reason for being in “The Apple Cart” is not so much to disconcert the cabinet as to give the audience the right cues for laughter; and the prefaces chiefly consist of cues for critics. But it is no use: “In my plays they — the critics — look for my legendary qualities, and find originality and brilliance in my most hackneyd claptraps. Were I to republish Buckstone’s “Wreck Ashore” as my latest comedy, it would be hailed as a masterpiece of perverse paradox and scintillating satire.13

It is the jest of Hahalaba14: the device contrived to attract the crowd to the entrance now covers the whole show. Its creator cannot get free of it, cannot speak through it to those he is trying to reach. When he leaves off capering and speaks directly, with serious passion and therapeutic wrath, what he gets is an idle clapping of the hands.

This legend obscures the real Shaw, not only from the idealists, who protest that they do not understand him, but from the Shavians, who protest that they do. Shavianism, no less than Taoism, or Behaviorism, suffers from its ardent converts as well as from its ardent enemies.

Mr. Shaw’s philosophy is not away with all ideals, but: “The ideal is dead: long live the ideal.” He is against current conventions because he wants better conventions; against schools as they are (his education was “interrupted” by ten years’ schooling) because they are not good enough; against most churches because “the godhead in me, certified by the tenth chapter of St. John’s Gospel to those who will admit no other authority, refuses to enter these barren places.”

A church must mirror the cathedral in us, must lift the spirit — as Shaw’s spirit was lifted in San Lorenzo — with a confirmation of godhead and ennobling power. The religion that shows through his writings — the Life-Force realizing itself in the developing will and awakening consciousness of man — is as positive and thrilling, as overwhelmingly assured of divine origin and authority, as any faith that sent a martyr to ecstatic immolation. It is the revelation of Ibsen’s Julian15 “prompted step by step to the stupendous conviction that he no less than the Galilean is God”.16

No cynic finds life “a sort of splendid torch” which he must make burn “as brightly as possible”. No perverse contriver of paradox leaves a system of philosophy in his work as consistent and true in its course, as a system of solar planets. Shaw’s writings are no less divinely inspired for being strewn with gaities instead of being strewn with records of the generations of Pashur17. There is perhaps an instinctive reason for the too-much talking that envelopes the thinking in his plays (apart from the reason that he has probably noticed that people do talk too much). We can no more take our thinking neat than we can take our electricity neat: there must be adequate insulation. Mr. Shaw would insist that he cannot make us think at all: the whole tenor of his plays is impatience with us because we never think; but he can give us a premonition of thinking. He drives the comfortable fogs out of our minds as the prophets of old drove demons out of the possessed, not with rites and incantations, but with railleries and caustic jesting.

Jester or not, he is a true prophet, and he is even now going the way of the other true prophets: moving in the inevitable curve from heterodoxy to orthodoxy, and achieving his apotheosis in the applause of fashionable audiences who accept him (as Elizabeth told Will Shakespeare England would accept the endowed theatre),18 not because they accept his serious faiths, but because it is the thing to do (“because it is her desire (…) to do humbly and dutifully whatso she seeth everybody else do”):19 greeting his stern wraths as well as his gay frivolities with polite laughter and an idle clapping of the hands.

- The newspaper was established in 1872 as The Manitoba Free Press and changed its name on December 2, 1931 to The Winnipeg Free Press. The Shaw article from July 18, 1931 therefore appeared under the Manitoba masthead. ↩

- This 1916 book collected three Shaw plays which appeared in 1912 and 1913. ↩

- See McLuhan’s library, 01372 and the additions to McLuhan’s library, mcluhan add 01372. ↩

- Alternately, the article was not by McLuhan, but by someone who immensely influenced him at the time — and for the rest of his life. But who could this have been? ↩

- A McLuhan citation from Shaw’s Preface to Three Plays for Puritans. ↩

- See, especially, his article ‘Public School Education’ (The Manitoban, Oct 17,1933): “We see hundreds of millions of dollars being spent annually in destroying (…) children.” ↩

- ‘Germany and Internationalism’, Oct 27,1933; ‘Germany’s Development’, Nov 3,1933; ‘German Character’, Nov 7,1933. ↩

- Is this a pointer Eliot’s Prufrock and/or Waste Land? ↩

- Pinero (1855-1934) and Jones (1851-1929) were English playwrights contemporaneous with Shaw (1856-1950). ↩

- Proteus is a character in Shaw’s Fanny’s First Play (1911). But the reference in both Shaw and McLuhan is, of course, to the shape-shifter in Homer and Virgil. ↩

- Duvallet is a character in Shaw’s The Apple Cart (1928). ↩

- McLuhan took this view of the theatre, and of all life as theatre, from his mother’s work as an “impersonator”. See The put-on. ↩

- John Baldwin Buckstone, 1802-1879, “Wreck Ashore”, 1834. ↩

- Lord Dunsany’s one-act play from 1928. ↩

- Ibsen, Emperor and Galilean, 1896. ↩

- Citation from Shaw’s The Quintessence of Ibsenism. Shaw comments on this “stupendous conviction”: “In his moments of exaltation he (Julian) half grasps the meaning of Maximus, only to relapse presently and pervert it into a grotesque mixture of superstition and monstrous vanity.” ↩

- Jeremiah 20:1 ↩

- McLuhan is referring here to Shaw’s 1910 play The Dark Lady of the Sonnets. ↩

- Ibid. ↩