Joyce’s illustrious countryman, Jonathan Swift, perhaps prompted by Bacon’s Novum Organum (1620), was the architect in 1726 of an engine which Joyce contrived to assemble following Swift’s design (from part 3, chapter 5, of Gulliver’s Travels). Finnegans Wake is the resulting working model:

The first professor I [Gulliver] saw was in a very large room,1 with forty pupils about him. After salutation, observing me to look earnestly upon a frame, which took up the greatest part of both the length and breadth of the room, he said, “Perhaps I might wonder to see him employed in a project for improving speculative knowledge, by practical and mechanical operations. But the world would soon be sensible of its usefulness; and he flattered himself, that a more noble, exalted thought never sprang in any other man’s head. Every one knew how laborious the usual method is of attaining to arts and sciences; whereas, by his contrivance, the most ignorant person, at a reasonable charge, and with a little bodily labour, might write books in philosophy, poetry, politics, laws, mathematics, and theology, without the least assistance from genius or study.”2 He then led me to the frame, about the sides whereof all his pupils stood in ranks. It was twenty feet square, placed in the middle of the room. The superfices [surface] was composed of several bits of wood, about the bigness of a die, but some larger than others. They were all linked together by slender wires. These bits of wood were covered, on every square, with paper pasted on them; and on these papers were written all the words of their language, in their several moods, tenses, and declensions; but without any order. The professor then desired me “to observe; for he was going to set his engine at work.” The pupils, at his command, took each of them hold of an iron handle, whereof there were forty fixed round the edges of the frame; and giving them a sudden turn, the whole disposition of the words was entirely changed. He then commanded six-and-thirty of the lads, to read the several lines softly, as they appeared upon the frame; and where they found three or four words together that might make part of a sentence, they dictated to the four remaining boys, who were scribes. This work was repeated three or four times, and at every turn, the engine was so contrived, that the words shifted into new places, as the square bits of wood moved upside down.

Six hours a day the young students were employed in this labour; and the professor showed me several volumes in large folio, already collected, of broken sentences, which he intended to piece together, and out of those rich materials, to give the world a complete body of all arts and sciences; which, however, might be still improved, and much expedited, if the public would raise a fund for making and employing five hundred such frames (…) and oblige their managers to contribute in common their several collections.

He assured me “that this invention had employed all his thoughts from his youth; that he had emptied the whole vocabulary into his frame, and made the strictest computation of the general proportion there is in books between the numbers of particles, nouns, and verbs, and other parts of speech.”

I made my humblest acknowledgment to this illustrious person, for his great communicativeness; and promised, “if ever I had the good fortune to return to my native country, that I would do him justice, as the sole inventor of this wonderful machine.”

Joyce’s machine improved on Swift’s only by substituting for “all the words of their language” all the possible sounds of all possible languages. The generation of words was therefore a laborious and prior work of his machine compared to Swift’s. Remarkably, however, it was found upon inspection that this laborious and prior work had already been performed by the world’s languages, each in its ‘turn’, anticipating, as it were, the FW engine and, arguably, obviating any need to transform sounds into words after all. For words had somehow already been generated!3

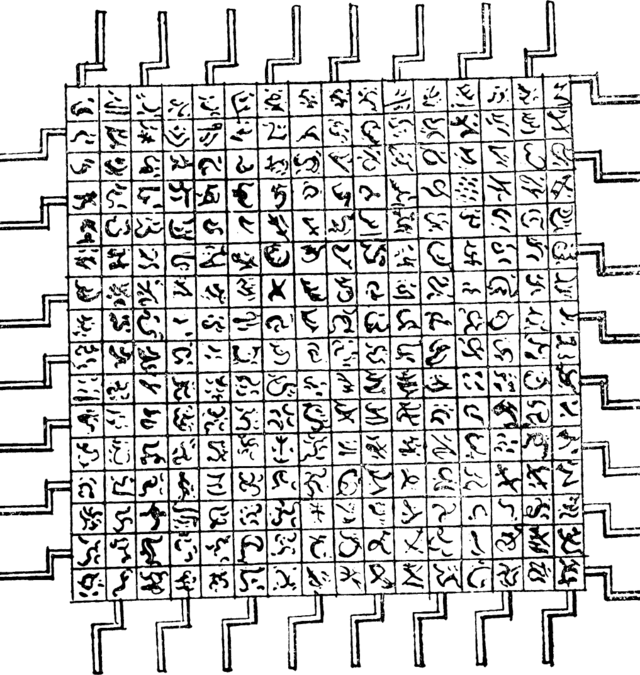

Swift’s diagram of the knowledge machine:4

- In “the Academy of Projectors”. The “projectors” were the technicians and inventors in Lagado society who were engaged in many exciting projects: extracting sunbeams from cucumbers; turning excrement into food; transforming ice into gunpowder; building houses from the roof down; using hogs to plow fields; training spiders to spin colored webs; treating colic by pumping air into people’s anuses. Technology and human needs had somehow become disconnected. ↩

- Swift had evidently foreseen AI. ↩

- Of course, Joyce’s machine also generated words for possible languages that were not, or were not yet, actual languages. Recognizing these words, let alone reading them, presents gigantic difficulties! How know when such a possible word from such a possible language begins or ends — let alone what ‘it’ might ‘mean’? And yet, don’t infants accomplish just this impossible task? ↩

- Swift’s diagram of the knowledge machine has 7 handles on one side, not 8 as on the other three sides (or 10 as Gulliver describes it). With this doubtless deeply considered feature Swift was able to introduce that surd into the generative process which is such an ineluctable aspect of language and knowledge. ↩