Innis’ May 1944 convocation address at the University of New Brunswick, ‘A Plea for the University Tradition’1 included warnings he was to reiterate at a similar occasion in 1945 at McMaster.2 But it also specified what the McMaster address only intimated: the fundamental link between force in the determination of truth and force in the determination of the international order between war and peace.

The 1945 McMaster address — given May 14, a week after VE day, May 8 — would repeatedly declare that “western civilization has collapsed”. His apparently more hopeful admonition the year before at UNB, as the war in Europe continued, was that “we [must] commit ourselves afresh to the maintenance of a tradition without which western culture disappears.”

Innis concluded that UNB address as follows:

Universities have grown beyond the high-school stage of development (…) and [their] maturity involves (…) proper recognition of the role of the scholar and of the university in the nation’s life. The efforts to maintain the traditions of the university are in themselves a testimony to these traditions. As recent graduates, we commit ourselves afresh to the maintenance of a tradition without which western culture disappears. (…) These [convocation] ceremonies — peculiar to an institution which has played the leading role in the flowering of western culture — remind us of the obligation of maintaining traditions concerned with the search for truth for which men have laid down (…) their lives.3

It is critical to appreciate the multiple circularities at play here in Innis’ famous “obscurity”. It was, he said, essential to the vocation of the university to maintain its own calling: “The efforts to maintain the traditions of the university are in themselves a testimony to these traditions.” The present and future of the university must be dedicated to the fresh cultivation of its own past traditions. Those traditions must be passed on. Those traditions, in turn, were focused on “the search for truth”. It was through this search that the “institution [of the university] has played the leading role in the flowering of western culture”. But this “leading role”, in its turn, was a “testimony” to that “flowering”. That is, the most important way in which the university could maintain its own traditions and so help to maintain the “tradition without which western culture disappears” was to function as an image of that “flowering”. As a “testimony” to it. Only this would constitute, “afresh”, the “proper recognition of the role of the scholar and of the university in the nation’s life.”

The calling of “the scholar and of the university” was to continue to cultivate the essential tradition of western culture by, first of all, being shaped by it. Their fundamental activity of “the search for truth” required a prior receptivity.4

Earlier in his address Innis specified the dynamic form to which the university community was called upon receptively to con-form:

Her traditions and her interest demand an obsession with balance and perspective — an obsession with the Greek tradition of the humanities. The search for truth assumes a constant avoidance of extremes and extravagance. Virtue is in the middle way. There are no cures. Always we are compelled to be sceptical of the proposal to cure the world’s ills. We cannot tolerate the dominance of any individual or of any group.5 (UNB)

The search for truth could not terminate in any “proposal to cure the world’s ills”. But neither could it terminate in an empty scepticism. Both were extravagant extremes. Instead “the scholar and of the university” had to cleave to “the middle way” ac-cording to which truth itself is essentially limited — but is nevertheless truth. As seen in all the physical sciences, “the search for truth” is the way truth truly manifests itself to human investigation. It is never fully present (so the search goes on), but it is also never fully absent (so the search goes on).

Innis drew ramifications for contemporary action and for historical perspective from this circular dynamic of reaction and action: “In our time [the university] must resist the tendencies to bureaucracy and dictatorship of the modern state.” (UNB) Elsewhere, Innis depicted these tendencies in terms of the burgeoning of irrationalism at the end of the nineteenth century.2 Since rationalism in Innis’ view “demand[ed] an obsession with balance”, these tendencies to irrationalism were specified in his UNB address as the turn to the extremes of imbalance:

In our time, unfortunately, the power of resistance to extremes has been greatly weakened. (…) the university has largely ceased as a vital force (…) by this ordeal of militarism. (UNB)

In 1944 the “ordeal of militarism” was, of course, the second world war. But it was also, and in Innis’ mind more fundamentally, an “ordeal of militarism” in regard to the university’s essential activity — the pursuit of truth. In his McMaster address, Innis cited Oliver Wendell Holmes to the effect that “truth is the majority vote of the nation that can lick all the others.” Where the essential receptivity required for truth was eclipsed by a militaristic activity “that can lick all the others”, truth, too, would be eclipsed — and freedom and democracy along with it. The balance required for all of these, beginning with truth, would disappear in favor of the one-sided — unbalanced — exercise of force.

Doubtless reflecting his close ties with classicists at the University of Toronto, Innis made the point at issue by citing Jacob Burckhardt on the society of classical Athens and its importance to the work of Plato:7

Festivals were a regular feature of life not a strain. Hence it was possible to develop that social intercourse which is the background of Plato’s dialogues.(…) People had something to say to each other and said it. Thus a general understanding was created. Orators and dramatists could reckon with an audience such as had never before existed.8 (UNB)

It is imperative to under-stand that “social intercourse” for Plato, and for Innis in turn, was not, first of all, a matter of what human beings happen to do in the market place. It was a matter, first of all, of truth itself, of what Innis called the “equilibrium of approaches” to “the mysteries of life and death”. Truth is internally limited and hence plural in itself. Submission to this plurality might be termed ‘internationalism’ and its refusal ‘isolationism’.

It was the “collapse” of that “general understanding” that led to the extremes of irrationalism and, ultimately, to the “century of war”:9

If we agree with Professor Whitehead that “The safest generalization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists in a series of footnotes to Plato,”10

we are forced to conclude that its power succumbed in the face of the Industrial Revolution and machine industry and the rise of romanticism. We have seen the effects of the disappearance of the Platonic tradition in the necessity of appealing to force as the unifying and dominating factor.11

The turn to force in the international order — or disorder — was the result, according to Innis, of the turn to force in a fundamentally misguided or unbalanced “search for truth”.12 It was the calling of the university to refresh its own traditions in the effort to return western culture to “the Greek tradition of the humanities” and to the required “obsession with balance” originated by it.

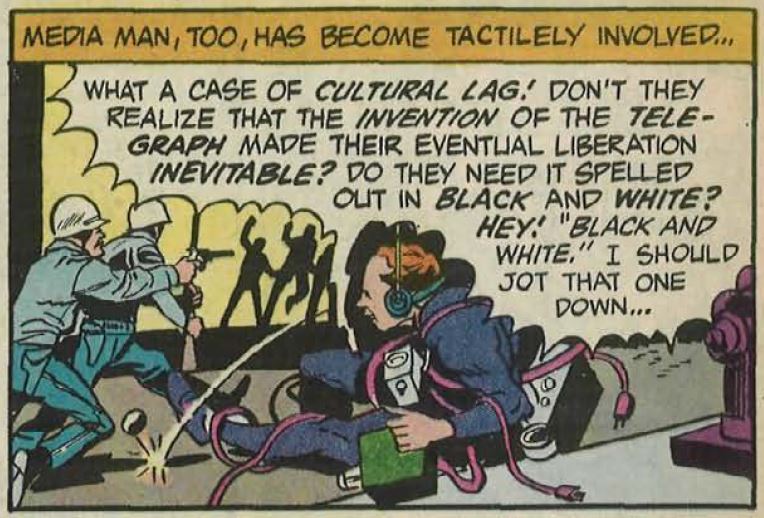

McLuhan specified this precisely in ‘The Later Innis’:

True social equilibrium, [Innis] saw, consisted in the simultaneous adjustment of the claims of space and time, power and knowledge. In the modern world the divorce between the between the city and the university reflects the loss of such equilibrium.

- Dalhousie Review 24:3, 1944, included in Political Economy in the Modern State. Citations from this address will be signaled by ‘(UNB)’. ↩

- See ‘Innis on the state of the world in 2021‘. ↩

- This passage from Innis offers a good illustration of what McLuhan termed his “ideographic prose”: “For in his later prose the linear development of paragraph perspectives is abandoned almost entirely in favour of the rapid montage of single shots. He juxtaposes one condensed observation with another, mounts one insight or image on another in quick succession to create a sense of the multiple relationships in process (…) This prose calls for steady contemplation of what is happening on the page. It is not intended to deliver an idea or a concept in a formula or in a package. It is an ideogrammic prose…” (‘The Later Innis’, Queen’s Quarterly, 60:3, 1953). ↩

- A decade later McLuhan would come to designate this necessary receptivity as response to “light through” toward us, not the exercise of “light on” from us. Not that “light through” was without intentional activity, however. Instead, like the painting of an icon, intentional activity in this mode was to be awaked and exercised as in-formed. ↩

- McLuhan in ‘The Later Innis’: “his deeply conscientious recognition of the just claims of both factors”. ↩

- See ‘Innis on the state of the world in 2021‘. ↩

- Innis was especially close with his UT classicist colleague, Charles Cochrane, with whom he famously took long walks around the Toronto campus in any weather. In addition, Innis’ mentor, and predecessor as head of the political economy department, E.J. Urwick (1867-1945), had written The Message of Plato, a Re-Interpretation of the Republic (1920). ↩

- Jacob Burckhardt (1818-1898) cited from Force and Freedom. These were notes drafted by Burckhardt in 1868 and published posthumously as Weltgeschichtliche Betrachtungen in 1910. The translation used by Innis appeared during the war in 1943 accounting for the forceful change in the title. ↩

- ‘An Economic Approach to English Literature in the Nineteenth Century’: “And so we entered the open seas of democracy in the twentieth century with nothing to worship but the totalitarianism of the modern state. A century of peace gave way to a century of war.” In his UNB address, Innis associated this turn to irrationalism with Gutenberg, nationalism and racism: “The printing press destroyed internationalism, and accentuated the importance of differences in language; these differences were widened by propaganda and by the use of such terms as ‘race’.” That is, printing effected imbalance by weakening the offsets to local nationalism and racism once supplied by the Church and by international Latin scholarship. ↩

- Innis slightly misquotes Whitehead here from Process and Reality: “The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.” ↩

- ‘University In The Modern Crisis‘, 1945. Cf, Innis on the state of the world in 2021. ↩

- If it is asked how force and imbalance are mutually implicating, an answer must begin with the fundamentality of “balance”. In order to deviate in either direction from this natural fulcrum, force must be exercised. ↩