Keys

to

Given

These are the last words of Take Today which are taken from the near last words of Finnegans Wake — just before its gapped last/first sentence.

[Note: Aside from the Burroughs essay in 1964, and Take Today in 1972, McLuhan discussed Joyce’s The keys to. Given! also in the 1974 ‘Medium Meaning Message’ (coauthored by Barrington Nevitt) — treatment forthcoming in Connubium 4. Cunnubium 2 discusses the Burroughs essay in aspects which are not repeated here: reference should be made to its footnote #2. Connubium 5 will discuss the Burroughs essay in yet another respect. (The footnote app broke in this post. So notes that would have been footnotes are included in the text in square brackets with double indentation — like this note).]

In his 1964 ‘Notes on Burroughs’, which amounts to a kind of prospect of his ‘connubium’ texts later in the decade, as well as of the retrospect of these same texts in Take Today, McLuhan discussed this donative — given! — gesture of the universe (dual genitive!!) as follows:

Finnnegans Wake provides the closest literary precedent to Burroughs’ work. From the beginning to end it [FW] is occupied with the theme of ‘the extensions’ of man — weaponry, clothing, languages, number, money, and media in toto. Joyce works out in detail the sensory shifts involved in each extension of man, and concludes with the resounding boast: The keys to. Given! Like Burroughs, Joyce was sure he had worked out the formula for total cultural understanding and control. The idea of art as total programming for the environment is tribal, mental, Egyptian.

[Note: What McLuhan means here by ‘Egyptian’ may stem from Sigfried Giedion’s ‘space conception’ presentation to the Explorations seminar: “Egyptian art, in which several different aspects of the same object are depicted upon horizontal and vertical planes.” Published in Explorations 6. Also see McLuhan’s letter to Wilfred Watson in October 1964 (discussion in Connubium 5): “Lewis (…) wanted to be Pontifex maximus of a magical priesthood. I suppose Yeats, Joyce and Pound had similar aspirations. Their priesthood was to create new worlds of perception. They were to be world engineers who shaped the totality of human awareness. Their pigments and materials were not to be paint or words but all the resources of the age. Such were the Pharaohs.”]

It is, also, an idea of art to which electric technology leads quite strongly. We live science fiction. The bomb is our environment. The bomb is of higher learning all compact, the ‘extension’ division of the university.

[Note: Pun very much intended with ‘extension’ division. McLuhan’s complex suggestion here is not just that the term ‘extension division’ captures the university’s ‘extension’ to all the other areas of modern life, like commerce and the military, but also and more, that all these activities are constituted by, and as, ‘extensions’ of human faculties. It is the latter which enables the former.]

The university has become a global environment. The university now contains the commercial world, as well as the military and government establishments. To reprogram the cultures of the globe becomes as natural an undertaking as curriculum revision in a university. Since new media are new environments that reprocess psyche and society in successive ways, why not bypass instruction in fragmented subjects meant for fragmented sections of the society and reprogram the environment itself? Such is Burroughs’ vision (…) he is trying to point to the shut-off button of an active and lethal environmental process.

[Note: McLuhan’s text has ‘shut-on’, not ‘shut-off’ or ‘shut-down’. As always with his writing, it is impossible to say if this was intended to provoke thought or was a typo. And if it was a typo, was it seen and approved by McLuhan, like ‘the medium is the massage’, or was it unseen and so comes to us, not from McLuhan, or not directly from McLuhan, but via McLuhan indirectly as a channeled message/massage from the unconscious beyond? This question suggests an important reason McLuhan was so enamored of talk.]

One way to perceive the extent of what was at stake here for McLuhan’s consideration (see next note for the reach of the term ‘con-sideration’) of “the environment itself” is to look at a presentation given by Sigfried Giedion to the Explorations seminar in 1955 in which he discussed “universal space” or “sidereal space” in terms of prehistoric and contemporary art:

[Note: The word ‘sidereal’ stems from Latin, sidus/sideris = star. Interestingly, this is also the root of the word ‘con-sider‘, which is to ponder, beyond the parameters of the solar system and the local galaxy, to the ‘star’ systems of the All. Giedion in ‘space conception’: “It is possible to give physical limits to space, but by its nature space is limitless and intangible. Space dissolves in darkness and evaporates in infinity.” This throws an interesting new light on the title The Gutenberg Galaxy which may be read as the Gutenberg ‘local ontology’! This explains the great success of that ontology in solving scientific and industrial problems. Forget the larger picture, concentrate on the smaller! The method of calculus! Forget the circle and concentrate instead on manageable straight-line segments! The death of God!]

Prehistoric Space Conception and Contemporary Art

[Note: This is the title of the concluding section of Giedion’s paper. Its overall title was ‘Space Conception in Prehistoric Art’. In the remaining 25 years of McLuhan’s life, he never tired of referring to Giedion’s ‘space conception’ (often in the context of ‘acoustic space’). These references to Giedion by McLuhan should be read as implicating univers-all or ontological ‘space’. Importantly, Giedion’s exploration of relative spaces was already central to the Explorations seminar in 1954 in the very session where ‘acoustic space’ emerged.]

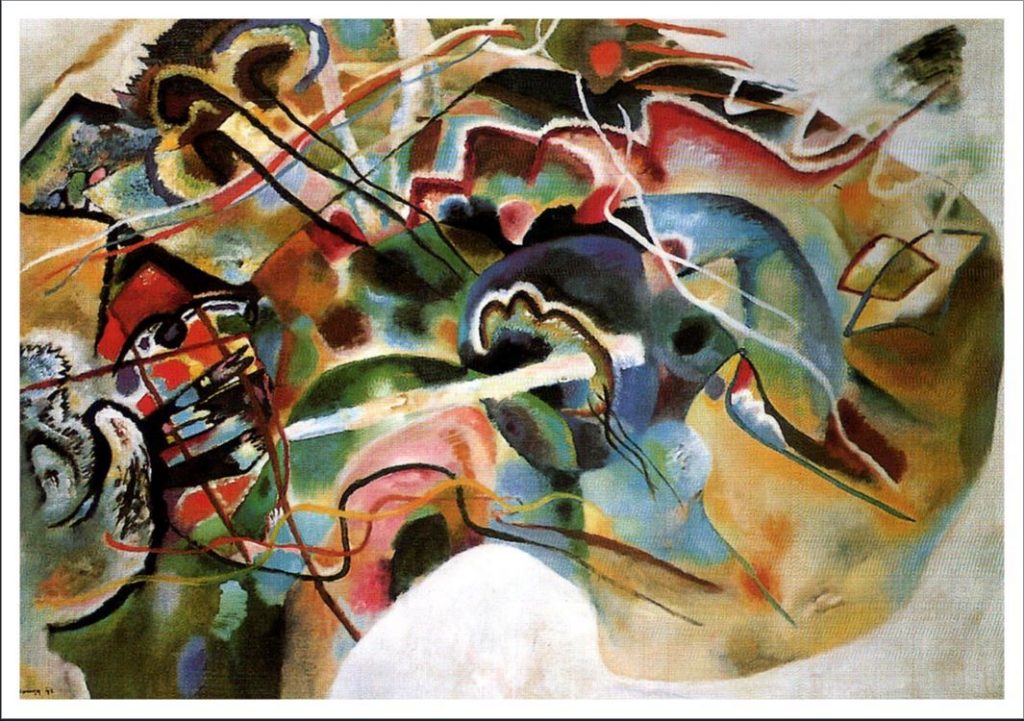

Abstraction, transparency, and symbolization are constituent elements of prehistoric and of contemporary art. The space in which they evolve has many things in common. Differences exist, but (…) at the moment only their inner relationship is what interests us. Their space is a space without background, a universal space. We are indebted to artists like Kandinsky and Klee for slowly being able to grasp the space conception of primeval art. They have opened our eyes to the pictorial [Giedion has pictured’ here.] organization, which is not exclusively dependent on the [fixed] vertical. In Kandinsky ‘s early work — e.g., The White Edge (1913) — we find a passion to exploit the newly gained freedom of lines and color set in sidereal space.

[Note: Kandinsky’s astonishing work formulates the exfoliation of ontology into and as the ontic via the color white (especially in the central thrusting — edge mirroring — burst) and the mass of colors which is white “pregnant with possibilities” (in Kandinsky’s words). Ontology does not lose itself in the ontic, but presents itself in it. Kandinsky re-presents that presentation (just as the red wavy lines in his painting re-present the white ones).]

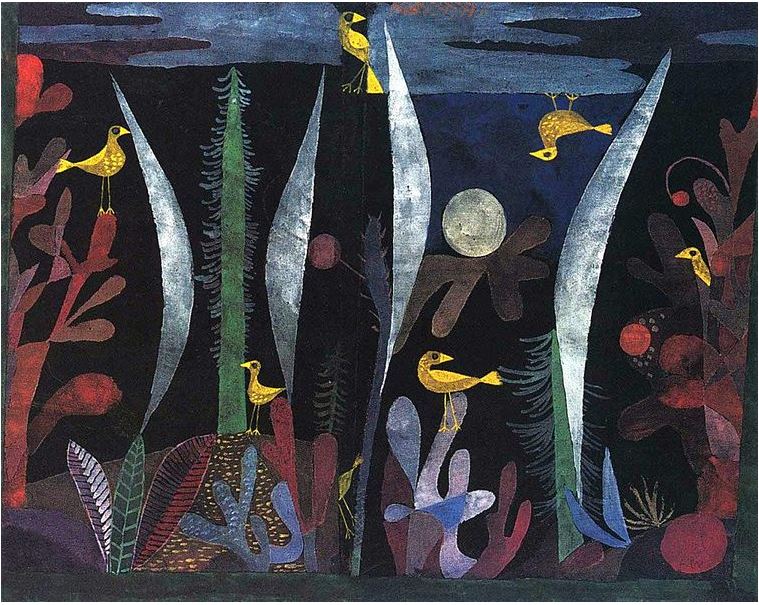

Paul Klee followed the same path, but in his own way. In one of his popular and most frequently reproduced paintings — The Landscape with Yellow Birds (1923) — the birds are sitting on fantastic plants, which defy botanical definition. On the upper rim of the picture one of the yellow birds is represented upside-down, indicating the spatial fluidity. One is reminded of underwater landscapes, where the body may move in all directions, unhindered by gravity.

Developed even further is the cosmic atmosphere in the far less known Ad Marginem (1930).

A planet hovers in the middle of a greenish undetermined background. Fantastic figurations grow along the margin. Plants, animals, eyes are forms in statu nascendi, polyvalent in their significance. Like primeval hybrid figures, they too cannot be confined to a definite zoological species. Here and there a calligraphically precise letter is inscribed in one of these forms, suddenly losing its everyday aspect and being re-transformed into a magic symbol from which it originated. From the upper rim, the naked stem of a plant is thrust down, and a bird with a long beak marches upside-down in a space without gravity. The forms reveal not even the remotest similarity with prehistoric motifs. Only the problem of constancy — as we understand it — comes to the fore, not in the sense of a rational, direct continuation [as in the Gutenberg galaxy], but rather as that property of the human mind which has been submerged for years in fathomless depths, suddenly reappearing on the surface. This happened in our time. (Explorations 6, 1955)

[Note: Giedion defined “the problem of constancy” or “question of the continuity” at the very start of his presentation: “The problem of space conception is everywhere under discussion. Scholars ask themselves, for example, What things have changed and what have remained unchanged in human nature throughout the course of human history? What is it that separates us from other periods? What is it that, after having been suppressed and driven into the unconscious for long periods of time, is now reappearing in the imagination of contemporary artists?” Giedion’s suggestion here is that human history is a matter of identity (what remains unchanged in it) and difference (what changes in it). Now when Giedion and McLuhan met in St Louis in 1943, McLuhan had just finished writing his PhD thesis on Nashe. Its central concern was with what remains unchanged in history — the trivium — and what changes in it — emphasis on one or other of the trivial arts. The immediate attraction between the two men may have turned on just this fulcrum.]

More than a decade before McLuhan’s discussions of the “macrocosm or connubium of a supraterrestrial nature” in the late 1960s (for texts and discussion see Connubium of Being 1), he and the Explorations seminar were already engaged with the question of making sense in a ‘macrocosmic’ or univers-all context. His ever-repeated attempts to specify a ‘strategy for survival’ by locating “the shut-off button of an active and lethal environmental process” must be seen as circling around the question of how to reinstate a sense for a grounding ontology in a world given over to an exclusive, purely ontic ‘reality’ — a ‘realty’ or ‘local ontology’ which, as Nietzsche specified, crumbles into nothing as soon as it is deeply ‘considered’:

The true world — we have abolished. What world has remained? The apparent one perhaps? But no!! With the true world we have also abolished the apparent one.

[Note: How the “True World” Finally Became a Fable: The History of an Error’, The Twilight of the Idols (1888). For the original text and various discussions of it see the Nietzsche posts.]