We have in our post-literacy come to the age of the classroom without walls. (1969 Counterblast)

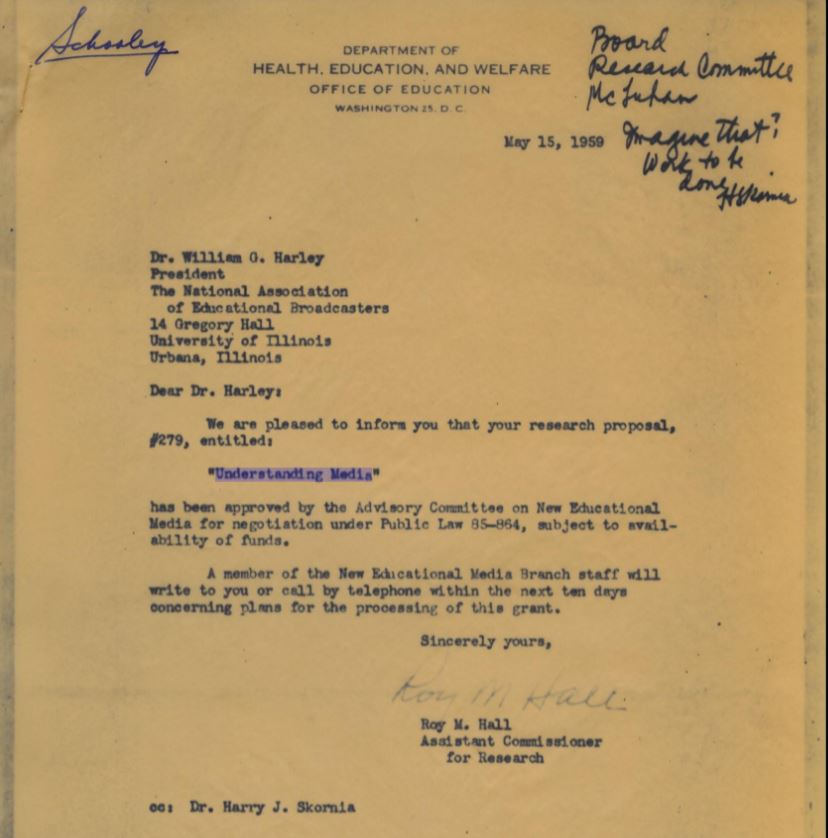

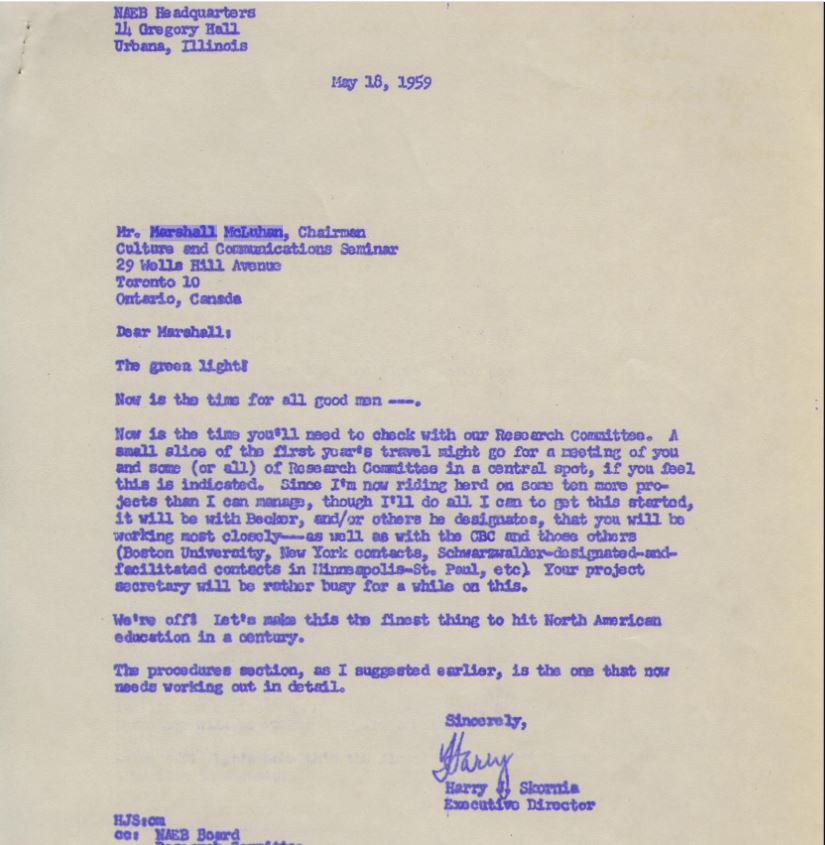

As described in First contact with the NAEB, McLuhan’s initial step towards work with the National Association of Educational Broadcasters took place in April 1957. But in the 3 years before this, he had renewed the interest in educational theory and practice that he had pursued in the 1940s (as seen in his 1943 PhD thesis, his 1944 lecture on ‘An Ancient Quarrel in Modern America’ and his 1947 education proposal to Robert Hutchins).1

A decade later, in the mid 1950s, he began to speak of the revolutionary effects of the new media on education, as marked by the catch-phrase “classroom without walls”.

Part of McLuhan’s impetus in this direction was doubtless his discontent with the situation of the humanities and social sciences — and with his own situation in that situation. More and more books, essays, theses, lectures, meetings and courses were flooding the world from these ‘disciplines’: but to what end? Hence his attraction to the work at MIT on cybernetics and to the communications research at Bell Labs. With these there was an objective engagement in stark contrast to the merely subjective, merely personal accumulation of benefits in the academy.

At the same time, and hardly unrelated to that situation in the academy, he saw that among the effects of the new media from comics to LPs to TV was the corrosion of the very foundations of education. Teachers from kindergarten to grad school lacked direction and students correspondingly sensed a disproportion between what they were learning in school and the world outside it. As a teacher himself, McLuhan felt called to address this confused situation and to do so by taking the sort of field approach that had proved so fruitful in the hard sciences from physics to cybernetics.

The idea, following Giedion, was to apply a kind of homeopathy where the very thing that was overturning the world — the electric revolution — would be interrogated for a way to right it again.

“Classrooms without walls” passages are given below in chronological order from McLuhan’s writings between 1954 and 1957. These paved the way for his life-changing engagement with the NAEB from 1958 to 1960 (just before McLuhan turned 50):

Erasmus was perhaps the first to grasp the fact that the [print] revolution was going to occur above all in the classroom. He devoted himself to the production of textbooks and to the setting up of grammar schools. The printed book soon liquidated two thousand years of manuscript culture. It created the solitary student. It set up the rule of private interpretation against public disputation. It established the divorce between “literature and life”.2 It created a new and highly abstract culture because it [print] was itself a mechanized form of culture. Today, when the [print] textbook has yielded to the classroom project and [to] the classroom as social workshop and discussion group, it is easier for us to notice what was going on in 1500 [namely, an educational revolution]. (…) Today, [again], when power technology has taken over the entire global environment to be manipulated as the material of art, nature has disappeared [along] with nature-poetry. And the effectiveness of the classroom has diminished with the decline of the monopoly of book-culture. If Erasmus saw the classroom as the new stage for the drama of the printing press, we can see today that the new situation for young and old alike is classrooms without walls. The entire urban environment has become aggressively pedagogic. Everybody and everything has a message to declare, a line to plug.3 (Sight, Sound, and the Fury, 1954)4

What Erasmus saw was that the printed book was to revolutionize education. He saw that the book gave new scope and power to the classroom. What we have to see is that the new media have created classrooms without walls. Just as power technology has abolished ‘nature’ in the old sense and brought the globe within the scope of art, so the new media have transformed the the entire environment into an educational affair. (Notes on the Media as Art Forms, 1954)5

The METROPOLIS today is a classroom6 (…) The [school] classroom [by contrast] is an obsolete detention home, a feudal dungeon. (Counterblast, 1954)

With the arrival of [book] print [around 1500], Erasmus and his humanist colleagues saw exactly what had to be done in the classroom. They did it at once. [By comparison,] with the arrival [300 years later] of the [newspaper] press, nothing was done. (…) Keeping in mind the extraordinary complexity and range of impact of the mere mechanization of writing by Gutenberg and measuring that impact merely by the total change of procedure in the sixteenth century classroom, I think we should try to imagine how sweeping a revolution should have taken place in our classrooms a century ago [with the arrival in the 1800s of the newspaper and its supporting social infrastructure (media) like the steam press and roads]. (An Historical Approach to Media, 1955)7

Writing was a visualizing of the acoustic which split off or abstracted one aspect of speech, setting up a cultural disequilibrium of great violence. The dynamism of the Western World may well proceed from the dynamics of that disequilibrium. If so, our present stage of media development suggests the possibility of a new equilibrium. Our craving today for balance and an end to ever-accelerating change may quite possibly be related to the very possibility of achieving that balance. (…) But it is plain that our new culture is not going to lean (…) on any one means of encoding experience or of representing reality. Already we are accustomed to a concert [or orchestration] of the arts, of the sensuous channels and of the media. And in this respect we shall resemble preliterate and prehistoric societies in the inclusiveness of our awareness.8 That means also that we shall tend as they did toward homogeneity of experience and organization [between individual and society, between subject and object]. Perhaps, therefore, we have in our post-literacy come to the age of the classroom without walls.

It was very hard at first for the contemporaries of Erasmus to grasp that the printed book meant that the main channel of information and discipline was no longer the spoken word or the single language. Erasmus was the first to act on the awareness that part of the new revolution was going to be felt in the classroom. He decided to direct the revolution from the classroom. I think the same situation confronts us. We are already experiencing the discomfort and challenge of classrooms without walls, just as the modern painter has to modify his techniques in accordance with art reproduction and museums without walls. We can decide either to move into the new wall-less classroom in order to act upon our total environment, or to look on it as the last dike holding back the media flood. (…) In such an age with such resources [as ours], the walls of the classroom disappear if only because everybody outside the classroom is consciously engaged in national and international educational campaigns. Education today is totalitarian because there is no corner of the globe or of inner experience which we are not eager to subject to scrutiny and processing. So that if the old-style educator feels that he lives in an ungrateful world, he can also consider that never before was education so much a part of commerce and politics. Perhaps it is not that the educator has been shouldered aside by men of action so much as that he has been swamped by high-powered imitators. If education has now become the basic investment and activity of the electronic age, then the classroom educator can recover his role only by enlarging it beyond anything it ever was in any previous culture. (Educational Effects of Mass Media of Communication, 1956)9

Print evoked the walls of the classroom. (…) The movie and TV [evoked the] classroom without walls. Before print the community at large was the centre of education. Today, information-flow and educational impact outside the classroom is so far in excess of anything occurring inside the classroom that we must reconsider the educational process itself. The [school] classroom is now a place of detention, not attention. Attention is elsewhere [engaged with the classroom without walls, aka the world outside the school]. (The Media Fit the Battle of Jericho, 1956)10

If “mass media” should serve only to weaken or corrupt our previously achieved levels of verbal and pictorial culture, it will not be because there is anything inherently wrong with these media. It will be because we have failed to master them as new languages in time to assimilate them to our total cultural heritage. (…) All of the new media are so many poetic means of packaging the age-old offerings of human culture. Sooner or later we shall recognize the need to study press, radio, movies, and TV as poetic forms in the classroom. (Classroom TV, 1956)11

The ways of official literacy do not equip the young to know themselves, the past, or the present. In the schoolroom officialdom suppresses all their natural experience; children of technological man are divorced from their culture, they cease to respond with untaught delight to the poetry of trains, ships, planes, and to the beauty of machine products. They are not permitted to approach the traditional heritage of mankind through the door of technological awareness; this [is the] only possible door for them [and it] is slammed in their faces. The only other door is that of the high-brow.12 Few find it, and fewer [still] find their way back [from it] to popular culture, and to the classrooms without walls that the new languages [of media] have created.13 (The New Languages, 1956)14

Before the printing press, the young learned by listening, watching, doing. So, until recently, our own rural children learned the language and skills of their elders. Learning took place outside the classroom.15 Only those aiming at professional careers went to school at all. Today in our cities, most learning occurs outside the classroom. The sheer quantity of information conveyed by press-magazines-film-TV-radio far exceeds the quantity of information conveyed by school instruction and texts. This challenge has destroyed the monopoly of the book as a teaching aid and cracked the very walls of the classroom so suddenly that we’re confused, baffled. (Classrooms Without Walls, 1957)16

- The twin sources of McLuhan’s early interest in education were Rupert Lodge and Sigfried Giedion. McLuhan had worked closely with Lodge at the University of Manitiba on the latter’s 1934 ‘Philosophy and Education‘ paper and his Cambridge Nashe thesis from 1943 represented a very extended development of its central idea — namely, that education is always in-formed by one of three mutually exclusive foundational structuring principles. Giedion’s Space, Time and Architecture, which McLuhan read just after he had submitted that thesis, argued that modern culture in all its manifestations suffered from a lack of ‘orchestration’. As McLuhan combined these notions from Lodge and Giedion in his 1954 ‘Notes on the Media as Art Forms’: “Every medium is in some sense a universal, pressing towards maximal realization. But its expressive pressures disturb existing balances and patterns in other media of culture. The increasing inclusiveness of our sense of such repercussions leads us today hopefully to investigate the possibilities of orchestral harmony in the multi-levelled drive towards pure human expressiveness.” This need for ‘orchestration’ fit with McLuhan’s notion that modernity suffered from the decline of ‘grammar’ among the foundational trivial arts — a notion he was still developing with ‘Grammars of the Media‘ in 1958. ↩

- The divorce between literature and life had already occurred in a relatively minor key with the advent of literacy in Greece. Indeed, some such ‘divorce’ is necessarily implicated whenever an area of life is isolated for focused attention and conceptualization. This cannot be achieved via the ‘rear-view mirror’. ↩

- In a way never seen before, everything in 20th century social and political life from motherhood to patriotism had become a product to be manufactured and sold. This introduced a bifurcation between ‘education’ outside the school, where everything was ‘up in the air’, subject to the suspicion of being only “a line to plug”, and inside the school, where everything — what to study and how to study it — was supposedly ‘grounded’. More, any attempt to heal this breach was necessarily seen as one more “line to plug”, thereby introducing a characteristic modern and postmodern complication to the care for social health. ↩

- Commonweal, 60:1, April 9, 1954. ↩

- Explorations 2, April 1954. ↩

- As cited above from ‘Sight, Sound, and the Fury’ (1954): “The entire urban environment has become aggressively pedagogic. Everybody and everything has a message to declare, a line to plug. the ads are its teachers.” ↩

- Teachers College Record, November 1955. ↩

- Much of this passage would later be used in the 1969 Counterblast: “Writing was probably the greatest cultural revolution known to us because it broke down the walls between sight and sound. Writing was a visualizing of the acoustic which split off or abstracted one aspect of speech, setting up a cultural disequilibrium of great violence. The dynamism of the Western world may well proceed from the dynamics of that disequilibrium. If so, our present stage of media development suggests the possibility of a new equilibrium. Our craving today for balance and an end of ever accelerating change, may quite possibly point to the possibility thereof. (…) But it is plain that our new culture is not going to lean very heavily on any one means of encoding experience or of representing reality. Already we are accustomed to a concert of the arts, of the sensuous channels and of the media. And in this respect we shall resemble pre-literate and pre-historic societies in the inclusiveness of our awareness.” ↩

- Teachers College Record, March 1956. ↩

- Explorations 6, July 1956. ↩

- Study Pamphlets in Canadian Education, #12, 1956. ↩

- This was McLuhan’s way, of course. ↩

- The first lines of this same paper on ‘The New Languages’: “English is a mass medium. All languages are mass media. The new mass media — film, radio, television — are new languages, their grammars as yet unknown. Each codifies reality differently; each conceals a unique metaphysics.” ↩

- Chicago Review, Spring, 1956, also in Explorations 7. ↩

- In the 1930s Eric Havelock at UT was describing education in pre-classical Greece in this way. See Havelock, McLuhan & the history of education. ↩

- Explorations 7, March 1957. ↩