Alchemy of Social Change, 19571

We have to know in advance the effect (…) of any change whatever. This is necessity, not ideal. It is also a possibility. There was never a critical situation created by human ingenuity which did not contain its own solution.

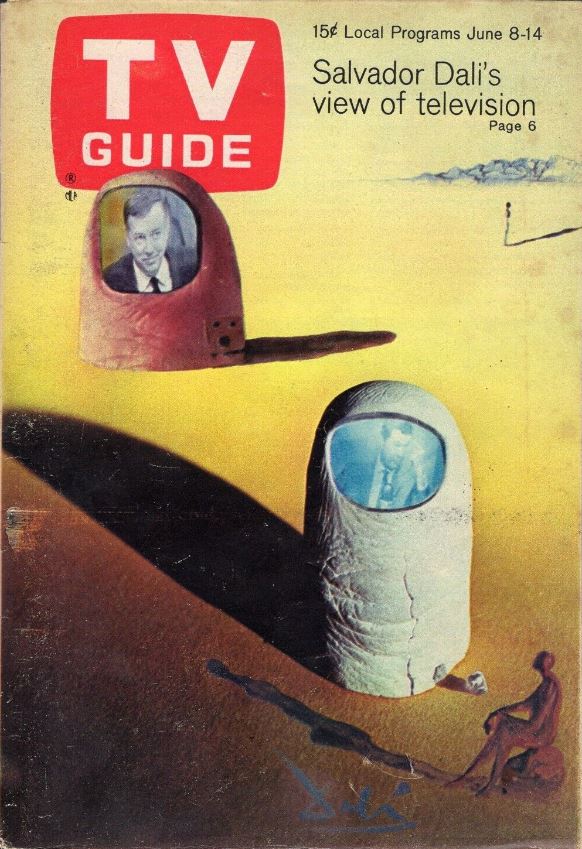

Technology, the Media, and Culture 1960

Let us return for a moment to that increasing awareness of the dynamics of process and learning and creativity which l suggest gains new force from the subliminal patterns of the TV image. In his Landmarks of Tomorrow, Peter F. Drucker has pointed to Operations Research as “organized ignorance”. It is a procedure in tackling problems which resembles the “negative capability”2 of Keats — a sort of intellectual judo. Instead of straining all available effort on a visible goal (…), let the solution come from the problem itself. If you can’t keep the cow out of the garden, keep the garden out of the cow. A. N. Whitehead was fond of saying that the great discovery of the nineteenth century was not this or that invention but the discovery of the technique of invention. lt is very simple, and was loudly proclaimed by Poe, Baudelaire, and Valéry, namely, begin with (…) the problem, and then find out what steps lead to [that problem].3 In other words, work backwards.

MM to Pierre Trudeau April 14, 1969

The real solution is in the problem itself, as in any detective story.

Take Today, 13

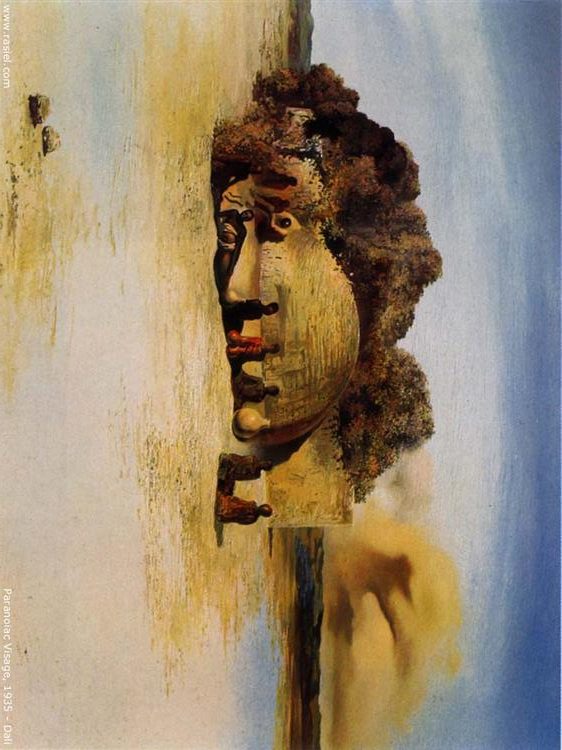

Our chief resources are the gripes and jokes, the problems and breakdowns, of managers4 themselves; for therein lie the solutions and breakthroughs via pattern recognition of the processes involved. Managing The Ascent from the Maelstrom today demands [new] awareness that can be achieved only by going Through the Vanishing Point.5

Take Today, 92

It is not possession of the solution, but the recognition of the problem itself that provides a resource and the answers.

Take Today, 103

All solutions are in the very words by which people confuse and hide their problems…

The Argument: Causality in the Electric World, 1973

The breakdown or hang-up is always in the connection whereas the breakthrough or discovery is inside the problem itself (…) Breakdown is the old cause in action, the extension of the old figure to [some]6 new ground. Breakthrough is the effect of understanding [the new ground] as the (…) cause [of the breakdown]. The solution is a figure that we can discover by organizing our ignorance and swarming over the ground. This process is encapsulated in the myth of Hercules in the Augean stables.

At the Flip Point of Time — the Point of More Return, 1975

Understanding that the entrance to knowledge is through the back door of ignorance is basic to an understanding of media and technology. It seems to be a human characteristic to hide the effects of our actions when they move out into the environments of services and/or disservices. Yet as James Joyce said of these man-made environments “when invisible they are invincible”. To free ourselves from the invincible effects of our own programs of organized activity,7 it is necessary that we inspect the ignorance systematically engendered by our applied knowledge.8

In sum: only with the problem do we have a solution.9

- Explorations 8. ↩

- As often broached by McLuhan, Keats described “negative capability” in a December 1817 letter to his brothers: “when a (hu)man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching-after-fact & reason“. ↩

- McLuhan has “the solution” here, not “that problem”. The substitution has been made to clarify his suggestion that, when identification is made of “what steps lead to” a problem, a “solution” to that problem will then be found in the modification of those steps. ↩

- Take Today is addressed to ‘managers’ and ‘executives’. Its subtitle is ‘The Executive as Dropout’. But its larger topic is the human subject as the ‘manager’ or ‘executive’ or ‘user’ of media (dual genitive). ↩

- In order to attain new awareness, transition Through the Vanishing Point is required. “Managing the ascent” is the movement between worlds of experience — from a world with the problem to another with its solution. This requires ‘vanishing’ since there is no world between worlds. ↩

- McLuhan: ‘the new ground’. But if ‘the new ground’ were known, the breakdown would not occur. ↩

- McLuhan’s phrases here, “effects of our own programs of organized activity” and “our applied knowledge” do not refer only to social activities. They also describe the genesis of individual experience as an “organized activity” and “applied knowledge”. The solutions to problems in McLuhan’s view lie first of all in thematizing a whole new genus of science based on media as the fundamental structures of artefactual reality — and artefactual reality includes all individual experience as well as all social activity. ↩

- See the following note: “all technical solutions have a new problem”. ↩

- At the same time, however, with the solution we have a problem. Barry Nevitt (?) in the Monday Night Seminar, January 22, 1973: “all technical solutions have a new problem” — οδός άνω κάτω… ↩