For the academic year 1939-1940, McLuhan had a sabbatical from his teaching position at St Louis University. He and his wife Corinne, who married on August 4, 1939, just before their departure for England, spent the year in Cambridge where McLuhan had obtained his second BA degree three years before (following his first from the University of Manitoba in 1933). During this time, McLuhan would receive his second MA degree based on that earlier work in Cambridge (again following his first MA from the University of Manitoba in 1934) and begin systematic research for his 1943 Cambridge PhD thesis. But the time he would have for this second stint in Cambridge was cut short by WW2, forcing the McLuhans to leave prematurely for North America at the end of May 1940.

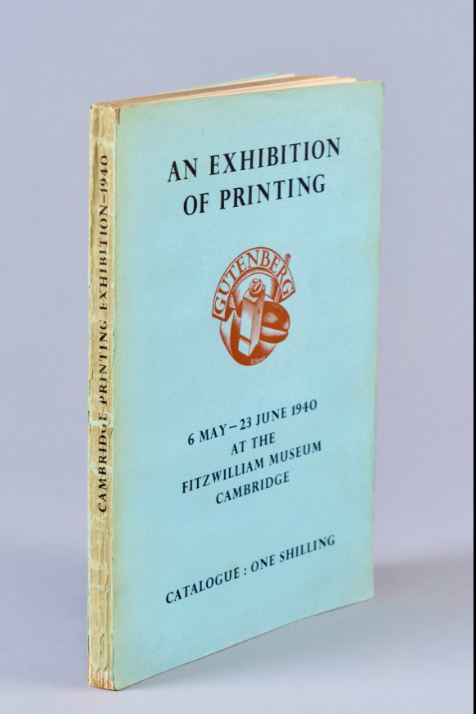

At just this time, immediately before the McLuhans’ hurried departure from Cambridge, “an exhibition of printing” was mounted at the Fitzwilliam Museum there celebrating the quincentenary of the invention of movable type by Johannes Gutenberg in 1440. The exhibition was scheduled to run from May 6 to June 23, 1940, but was closed after only 10 days, on May 16, due to the possibility of bomb damage to it from the intensifying air war.

The excellent History of Information website records the ‘Foreword’ to the exhibition catalogue as follows:

There is no moral to this exhibition. It aims at portraying, as objectively as possible, the uses to which printing from movable type has been put since Gutenberg and his associates invented it five hundred years ago; the spread of knowledge more quickly and accurately than was possible before, the storing of human experience, the providing of entertainment, the simplification of the increasingly complicated business of living. Those books, papers, and other printing have been chosen (so far as the difficulties of the times would permit) which made most effective use of the medium of type; in other words, those which, composed and multiplied, most strongly influenced people and events. Others have been chosen for their illustration of events and trends of particular importance or interest; others again for their intrinsic curiosity as examples of the exploitation of print. All are shewn so far as possible in the original editions in which they were first presented to the world.

The exhibition has been designed therefore to illustrate the development of man’s use of movable type as a tool; its spread from Mainz through the countries of the world, through all the fields of knowledge, through the whole range of man’s activities. Running through the story another theme presents itself and draws occasional comment — the development of the actual form of printing. The technical display deals with the old and modern methods fo type-founding and composition, and briefly illustrates the development of type design. That part of the exhibition is education; for the rest, though there is much to learn from it, it does not set out to teach. It is simply an illustration to that proud but unattributed saying:

With my twenty-six soldiers of lead I have conquered the world.1

Although McLuhan would certainly have heard of this “exhibition of printing”, he may or may not have visited it. However that may have been, 11 years later in March 1951,2 he would write to his University of Toronto colleague, Harold Innis, that “the modern press” as a “technological form” (“the medium of type”, as the exhibition catalogue has it) was “efficacious far beyond any informative purpose”. That is, the medium of print was “efficacious far beyond” any particular message it may have been used from time to time to convey:

[Mallarmé] saw at once that the modern press was not a rational form but a magical one so far as communication was concerned. Its very technological form was bound to be efficacious far beyond any informative purpose.3

In the year after that, in 1952, he would announce in a letter to Ezra Pound:

I’m writing a book on “The End of the Gutenberg Era”.4

The book was profiled in the letter to Pound and its second section, “Invention of printing”, had this outline:

- Mechanization of writing

- Study becomes solitary

- Decline of painting music etc in book countries

- Cult of book and house and study

- Cult of vernacular because of commercial possibilities

- Republicanism via association of simple folk on equal terms with “mighty dead”.

It would be a further 10 years later, in 1962 — 22 years after the 1940 Cambridge exhibition — when McLuhan would finally publish the book under the new title of The Gutenberg Galaxy.

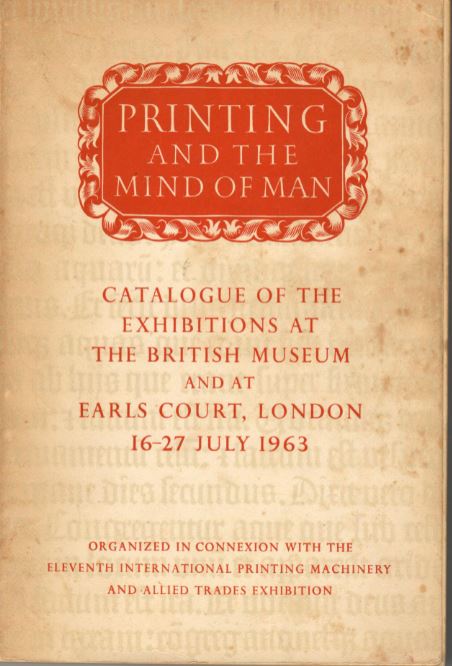

Now in 1963 another exhibition, Printing and the Mind of Man, was held in London which modeled itself on the 1940 one in Cambridge.

This 1963 catalogue noted:

We pay tribute to the organizers of the Gutenberg Quincentenary Exhibition of Printing, assembled at Cambridge in 1940 (and prematurely disassembled because of the risks from enemy bombing). It was our original inspiration for several sections of our display, and its invigorating catalogue has been our constant friend.

The 1967 edition of the catalogue has a slightly different acknowledgement:

A partial attempt [“to illustrate (…) the internal development of (…) printing as a craft”] had, indeed, been made in the Gutenberg Quincentenary exhibition at Cambridge in 1940. This was a suggestive forerunner for several sections in our display, and its invigorating catalogue was a constant friend.

In regard to the work of Marshall McLuhan, several interesting questions are suggested by this history:

- did the 1940 Exhibition of Printing in Cambridge, mounted while McLuhan was on sabbatical there, plant the seed, not only for his 1962 book, The Gutenberg Galaxy, but even for his one lifelong topic of “the medium is the message”?5

- did rumors of the impending 1963 exhibition, Printing and the Mind of Man, finally motivate McLuhan to get The Gutenberg Galaxy out the door at last in 1962? (As noted above, he had been working intermittently on the book since at least 1952!)

- The History of Information website has an image of this ‘Foreword’. ↩

- What happened between 1940 and 1951 to recall or otherwise activate what McLuhan knew of technological innovations, particularly in the area of communications? Answers to this question point in several directions, the most important of which is: McLuhan’s move to the University of Toronto in 1946 and his exposure there to the work of Harold Innis and of Eric Havelock. By the middle 1940s, both of these professors, the first in Political Economy, the second in Classics, had begun to research, apparently influenced by each other, the role of communication media in historical change. Innis was already publishing in the area and Havelock’s research on the role of orality in Greek culture was widely discussed in the Toronto academic community. Now from his early mentors at the University of Manitoba, particularly Rupert Lodge, McLuhan had long been exposed to the notion that all human experience is preformed by a multiplicity of irreducible forms. His 1943 Cambridge PhD thesis examined the history of this notion in terms of the educational trivium over the 2000 years between between classical Greece in 400 BC and Elizabethan England in 1600. A 1944 lecture (published in 1946) brought this “ancient quarrel” of irreducible forms into the present. But how were these forms to be generally recognized for open investigation? And what accounted for the relative rise and fall of these forms over time? ‘Media’ (although not in a literal sense) would eventually answer these questions for McLuhan. But this realization would take decades and remained in an inchoate form until the late 1950s. In fact, in a 1975 conversation with Nina Sutton (given in James Tenney and Wolfgang Köhler) McLuhan referred even to his 1964 Understanding Media as “the early time” of his thinking! ↩

- McLuhan to Harold Innis, March 14, 1951, Letters 221. McLuhan would coin the phrase, “the medium is the message”, after 7 more years had passed, in 1958. See The medium is the message in 1958. ↩

- McLuhan to Ezra Pound, July 16, 1952, Letters 231. The End of the Gutenberg Era remained the working title for McLuhan’s book throughout the 1950s. It was changed to The Gutenberg Galaxy in 1960 or 1961 to get away from the chronological implications of ‘era’ — McLuhan had come to see that media as structural possibilities are ‘all at once’. ↩

- An important question (further to note 2 above): Did McLuhan engage the topic of ‘the medium is the message’ long before his coining of the phrase in 1958? Consider only that his 1943 Nashe thesis treated the three trivial arts as media in several senses. Each was regarded as a cultural medium in the laboratory sense of promoting identifiable growths. At the same time, each was regarded as a structural form (‘medium’ in another sense) whose recognition could enable collective investigation of the cultural field. These insights lie at the heart of McLuhan’s contribution, along with his slightly later one that media are ratios and that ratios may systematically be expressed in terms of their middles. ↩