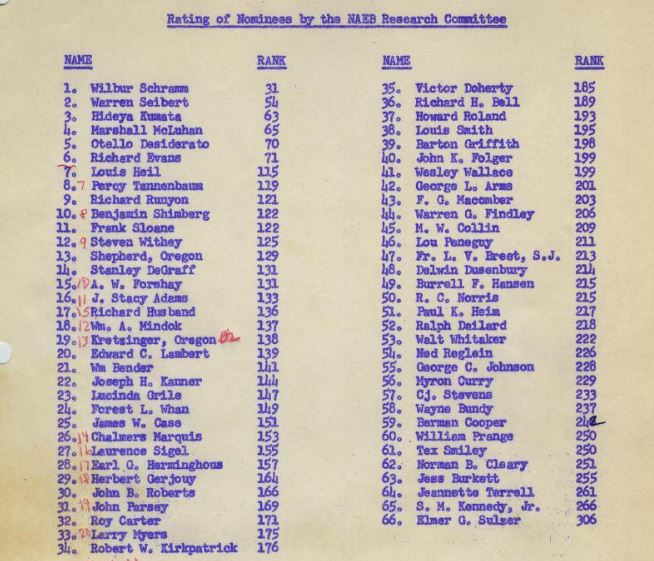

McLuhan’s Understanding Media project with the NAEB was approved for funding through Title VII of the National Defense Education Act in May 1959. At the end of that month, on May 29, McLuhan wrote Harry Skornia:

Shall spend much of the summer getting things lined up for your [NAEB research] committee so that they can give us maximum aid. Shall send many memos and suggestions of possible procedures. Also, the Gutenberg Era can be circulated in mimeo to all of them. Macmillan just wrote asking for it. I don’t think any better approach to [the] Understanding Media [project] could be developed than the Gutenberg Era MSS.

As shown by references in The Gutenberg Galaxy with dates later than this letter, McLuhan would still do considerable work on the manuscript before it was published in 1962. But by the spring of 1959 The Gutenberg Era — what was to become The Gutenberg Galaxy1 — existed in manuscript form that was complete enough, or at least within sight of being complete enough, for McLuhan to consider showing it to potential publishers and to the NAEB committee that would, at least in prospect, be guiding his project.

In regard to that project, the twin topics of the Gutenberg book were:

- what happened in history that led to the dis-covery of the understanding of media (including the imperative need for that discovery)?

- what happened in history that assisted in that dis-covery?

The first was a diachronic or horizontal story, the second a synchronic or vertical one. Like two eyes estimating a distance, or two I’s participating in a dialogue, or two ayes confirming a contract, the two together would both be needed to bring McLuhan’s project into focus.2

- The change in title from ‘Era‘ to ‘Galaxy‘ signaled McLuhan’s growing awareness of the question of time to the project of understanding media. He came to see that it was a question of rival mosaics whose relation, although not without a historical dimension, was first of all one of contemporaneous rivalry. An ancient quarrel. All at once. The great trick was to assume by a kind of backwards flip that mosaic which was necessary to ‘put on’ in order to begin an investigation of mosaics. The NAEB research committee, like the McLuhan industry today 40 years after his death, was unable to subject itself to this demand. ↩

- The parallel with chemistry is exact. For billions of years, the history of the planet took place, so to say, chemically. But even when humans came to learn how to manipulate that chemistry through cooking, tanning, brewing, etc, and eventually through smelting, they did not understand what they were doing except in terms of practical results: to achieve such and such an end, follow these steps. Ultimately, however, both through evolving practical experience and theoretical considerations taking off from the Greek miracle, the field of chemistry was dis-covered and became subject to investigation. This happened only two centuries ago. Chemistry had always been a possible object of understanding, but this possibility had to be unearthed through a laborious historical process lasting, as it now seems, hundreds of thousand of years. Then, once chemistry was born in our understanding, it could be understood through it both what had always been going on in the world, including in our own bodies, and even beyond our world in the stars — and what in particular had gone on leading to that eventual birth. Understanding media, in McLuhan’s estimation, could be achieved in an analogous way — and had to be achieved if the fruits of civilization where not to be destroyed by our insouciance. ↩