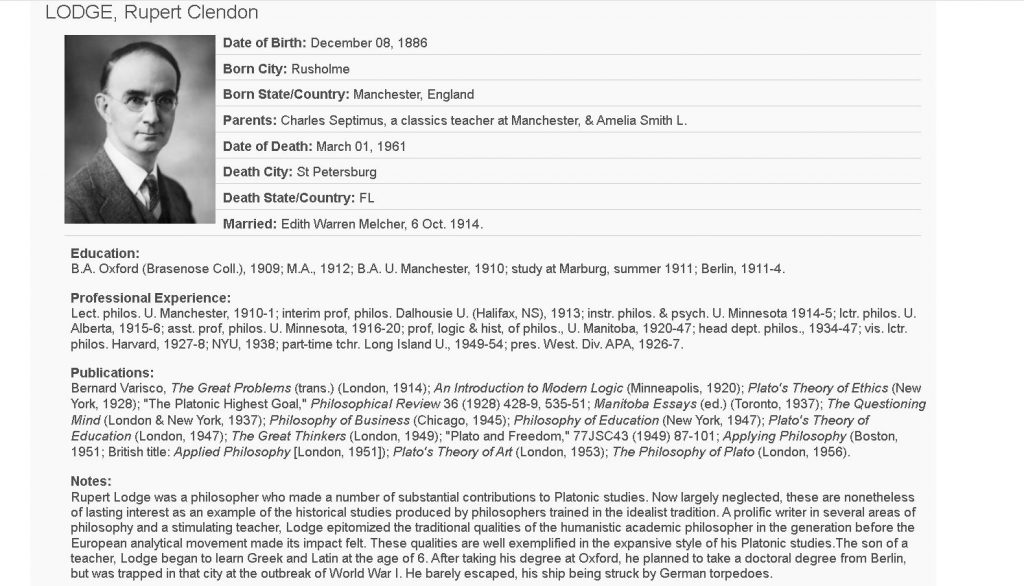

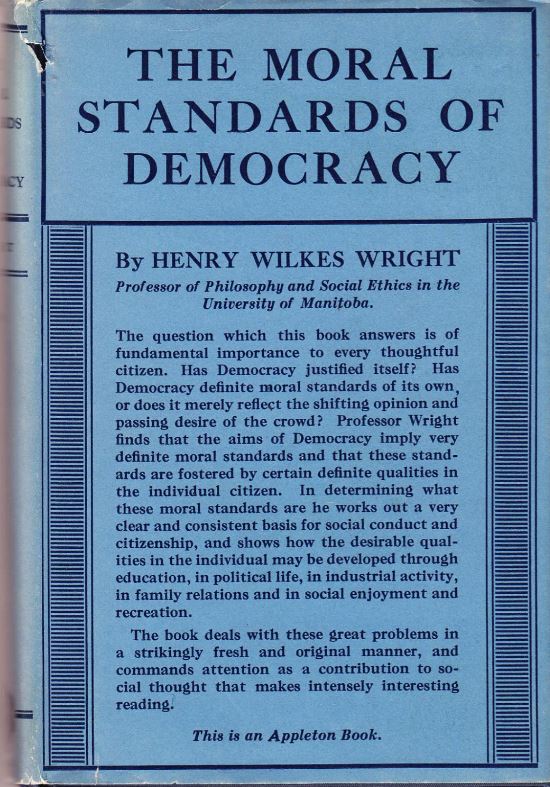

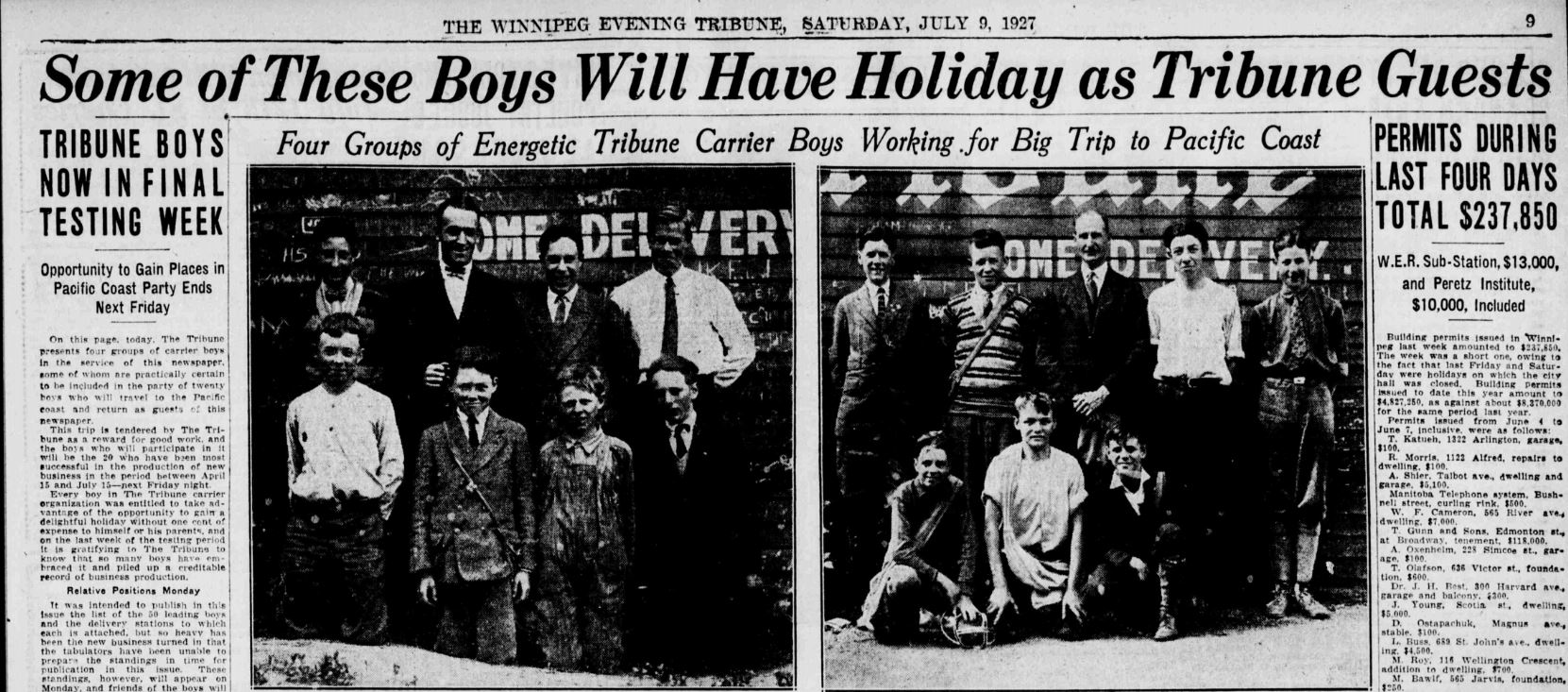

Sometime soon after McLuhan transferred from Engineering to Honours English in 1929, in 1930-31 perhaps, he took the UM introductory philosophy course which was given in two halves, one taught by Rupert Lodge, and the other by Henry Wright. Presumably Lodge concentrated on Plato and Wright on modern authors.

One of the books studied in Wright’s part of the course was his own 1925 volume, The Moral Standards of Democracy:

McLuhan’s “heavily annotated” copy of Moral Standards remains in his library which the McLuhan family has donated to the rare book collection at Fisher Library of the University of Toronto.

The museum will feature blowups of pages from Wright’s book and of McLuhan’s notes in it.

Here is Wright on pages 86-87 of Moral Standards (all emphasis added):

In modern society, association by direct personal contact has been supplemented and, so far as social organization is concerned, has been largely replaced by impersonal association and indirect contact. Now these activities of indirect contact and communication proceed through the intermediation and instrumentality of mechanical agencies. And these agencies themselves are extensions in the physical world of those bodily organs of inter-communication and personal association (…) possessed by every human being; namely, those of oral and written speech, of practical contrivance and construction, and of aesthetic perception and artistic creation. Hence these three activities of intercommunication (…) are fundamental in the double sense of determining both the direct personal association of human individuals with one another, and also the indirect association of millions of individuals as fellow citizens and fellow workers. (…) Moreover such chance as there is of giving personal value to indirect and impersonal contacts brought about by modern large scale social organization, and thereby making it a MEANS for realizing that comprehensive social community for which democracy stands, depends altogether upon our understanding this social machinery as an extension into the physical world of the three activities of personal intercommunication: [1] discussion [“oral and written speech“], and [2] cooperation [“of practical contrivance and construction”], and [3] imaginative sympathy [“aesthetic perception and artistic creation“].

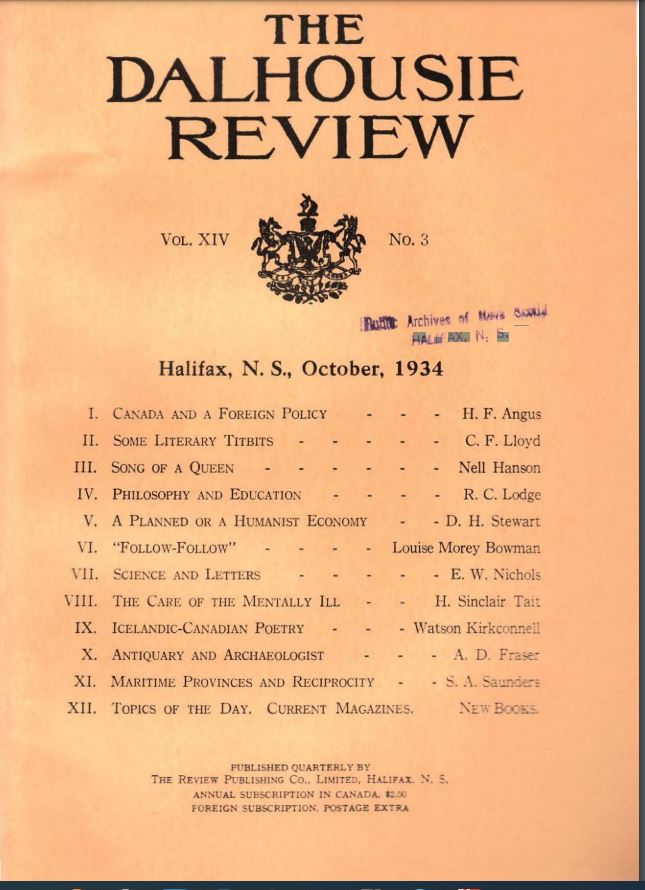

Here is Wright again in 1937 in ‘Mechanism and Mind in Present-Day Social Life’, which he contributed to Manitoba Essays: Written in Commemoration of the Sixtieth Anniversary of the University of Manitoba (ed Rupert Lodge):

- Machine technology and the mechanical instruments it has devised for facilitating the outward activities and inter-play of human individuals on a large scale have had the effect of externalizing the interests and activities of man to such a degree that his inner, personal life is becoming impoverished and his spiritual faculties atrophied through disuse.

- The enormous enlargement which radio and film have given to the scope and range and diversity of sensory stimulation is too obvious to need illustration. The same may be said of the effect of automobile, aeroplane, machine tools, electrical appliances, etc., upon man’s powers of outward action and motor performance. But no such adventitious aids have been supplied by the arts of technological invention to the inner interpretative processes of rational reflection and creative imagination. Thus, in a generation preoccupied with new ranges of sight and hearing, and fascinated by a variety of new mechanical tools and toys, these inner activities have for the time at least been relegated to the background and allowed to wither from neglect.

- No more urgent or pressing problem confronts modern society than [the question] of the influence of mechanism and mechanical intermediaries upon the character and relations of men.

- What measures it is practically wise to adopt, however, will depend upon the relation of mechanism and mechanical instrumentalities to the nature of man.

- The characteristic activity of the human organism is not mechanical, topographical, and aggregative, but is rather dynamical, configurational and organismic.

- The question [must be posed] of the influence on present-day social life and personal development of the newly invented machinery of social interaction and inter-communication.

- The question [must further be posed] of how the technological instruments which in their great and amazing variety dominate our civilization and differentiate it from every previous stage of human history are related to human nature and the personal associations of men.

- These technological instruments which have revolutionized the social life of man, from telephone and radio to automobile and aeroplane, from electrical household appliances to automatic machinery for (…) manufacture of economic goods and the reproduction of art products, are extensions through physical forces and mechanical intermediaries of man’s bodily organs.

- Consider in the first place all mechanical devices for the transmission of fact and opinion: telegraph and telephone and radio, the newspaper and colour-press, billboard, illuminated sign, and news-reel. These are all of them MEANS of increasing through physical intermediaries the range both in space and time, and the social influence, of man’s powers of articulate speech, oral and written.

- These are one and all mechanical MEANS for making available for popular appreciation and enjoyment on a practically unlimited scale the products of man’s powers of emotional expression and aesthetic perception. Now if this is a fact, and I do not see how it can be denied, there follow from it consequences of genuine, far-reaching social importance. The products of modern science and invention are not correctly understood as belonging to another, alien world, a world of matter and mechanism, forever separate and divorced by essential nature from that other inner realm in which alone are realized the distinctively human and truly personal values, such as truth, practical goodness and beauty, the “imponderables” of the spirit. On the contrary, they, like the organic agencies whose power and range they enormously augment, are in veritable fact projections of human personality itself and [the potential] MEANS of satisfying the distinctively personal interests of man.

- These mechanical instruments and devices which dominate the modern social scene (…) are veritable extensions of the powers of human personality and effective [potential] MEANS for the co-operative realization of the most comprehensive and enduring values of personal and social life.

McLuhan’s entire intellectual life might well be understood as the extended interrogation of Wright’s observations:

- “the inner interpretative processes” — how are these to be specified? what field encompasses them? how does this field of Wright’s “inner realm”1 feed back into its own investigation? if all specification falls within the field, how begin it without already having begun it? how get out of the endless circularity that seems to be implied here? the maelstrom…

- our “inner, personal life is becoming impoverished and [our] spiritual faculties atrophied” — since humans can never not exercise their “inner interpretative processes”, their “spiritual faculties”, how could these “processes” ever become “impoverished” and “atrophied”? how is this even a possibility for humans? what does such a possibility imply about the complex nature of human being?2

- and how does this possibility feed back into the investigation of such questions? could investigation itself become “impoverished”? is the “Waste Land” first of all a matter of our “inner interpretative processes”?

- “the influence of mechanism and mechanical intermediaries” — can investigation into media (“understanding media”) prove to be an Ariadne’s thread for the labyrinth of these questions?

- McLuhan’s later “interior landscape”. ↩

- Wright suggests that there are different “fundamental” possibilities that originally structure human experience: “The characteristic activity of the human organism is not mechanical, topographical, and aggregative, but is rather dynamical, configurational and organismic.” What does ‘characteristic’ mean here? How does an individual or society ‘switch’ between these modes? What sort of time or times is implicated here? ↩

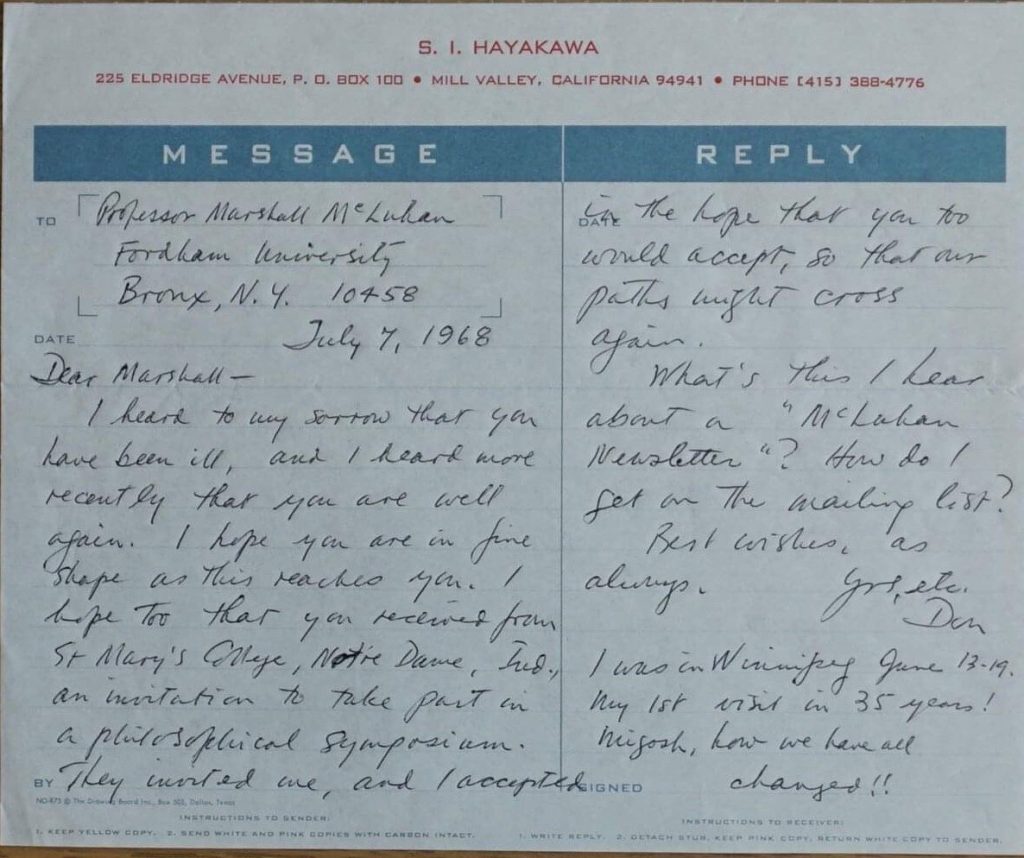

July 7, 1968

July 7, 1968