McLuhan graduated from Kelvin in 1928:

He then entered the University of Manitoba School of Engineering, later reporting that he was looking for a way to support himself while he went about his real work of research and writing. But the deeper reason for his choice of Engineering may have been his need to extricate himself from his father’s impractical lyricism and his mother’s literary caricatures. However that may have been, McLuhan’s one year in Engineering brought him a lifelong friend in Tom Easterbrook.1

Tom and I both started off [university] in Engineering [in the fall of 1928] and because of our long periods of study during the summer, we were able to upgrade ourselves into Arts. I read myself out of Engineering by my long summer [of 1929].

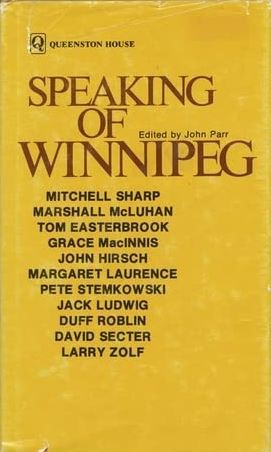

This was McLuhan in 1970, forty years later, in Speaking of Winnipeg:

Again in Speaking of Winnipeg, the two described the argumentative rambles they took at the time:

We had an absolute agreement between ourselves to disagree about everything and this kept up (…) a very hot dialogue from morning to night for years in Winnipeg which carried us on foot across town at night, late at night till three or four in the morning, back and forth across the city.

The McLuhans lived south of the Assiniboine River in Winnipeg, the Easterbrooks north.

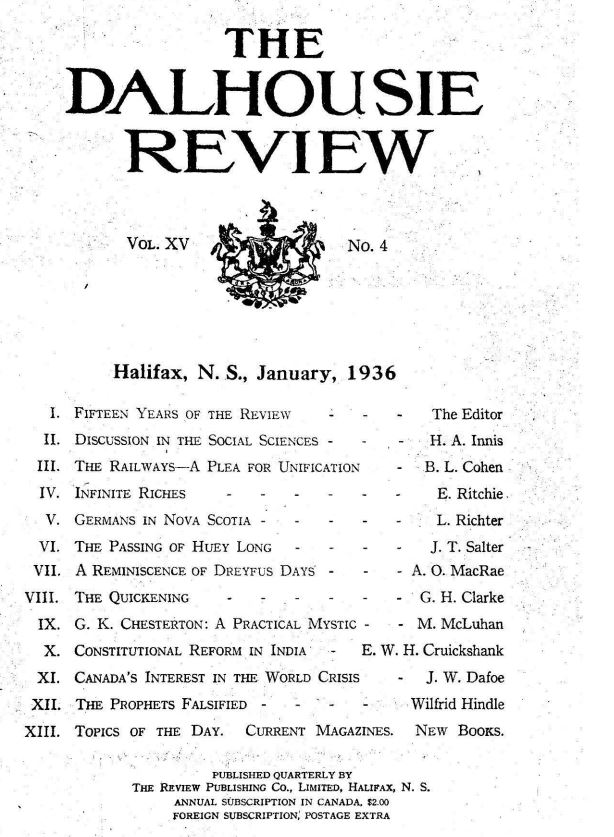

It was during their UM days, apparently in 1931, that McLuhan came to read G.K Chesterton through Easterbrook. This provided one of the initial steps towards McLuhan’s conversion in 1937 and became the subject of his first academic paper in 1936: ‘G.K. Chesterton: A Practical Mystic‘:

Another contributor to the issue was Harold Innis — when the issue appeared Innis was Easterbrook’s adviser at Toronto and increasingly his good friend.

In 1932 McLuhan and Easterbrook toured England together, working their way across the Atlantic on a cattle boat. This mode of transportation seems to have been popular option for young Winnipigeons at the time, doubtless due to Winnipeg’s role as the collection point for rail shipments between eastern and western Canada. Five years earlier Hayakawa got to Montreal in the same way. As recounted in his oral history:

Soon after graduating with my B.A. from the University of Manitoba, Gerard, Professor Allison’s oldest son,2 and I decided to take a cattle train to Montreal for a summer adventure. I cannot reconstruct how or where we had our meals on that train or where we slept. The reason we were getting a free ride across the continent is that, in the event of a train derailment or wreck, the cattle would start running away and the railroad wanted a few extra men on the train to help recapture them. We really had nothing to do — no duties — except in the event of a train wreck and escaping cattle.

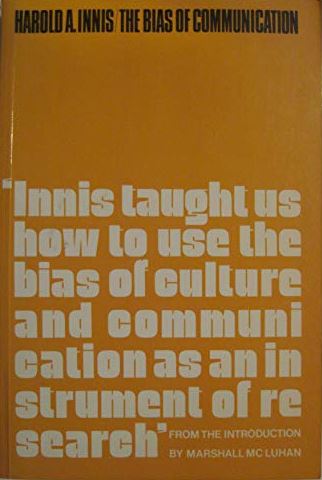

After their UM degrees, McLuhan and Easterbrook continued their studies, McLuhan at Cambridge and Easterbrook at the University of Toronto. That Easterbrook’s advisor was Harold Innis decisively impacted McLuhan’s career when Easterbrook brought Innis and McLuhan together in 1948. Meanwhile, McLuhan in Cambridge and Easterbrook in Toronto remained in close contact through McLuhan’s mother and brother, who had moved from Winnipeg to Toronto and knew Easterbrook well through Marshall in Winnipeg.3

The Innis connection via Easterbrook would prove essential to McLuhan’s later work. For it was Innis who brought McLuhan to concentrate, not on ideas as he had in his PhD thesis on the educational trivium, but on the embodied ideas of technology. He came to see how human beings live in their ideas through technology — beginning with language.

In the 1950s Easterbrook was one of the 5 professors leading the Culture and Communication seminar — three of them from Winnipeg (McLuhan, Easterbrook and Carl Williams) with their trilateral relationship going back a quarter of a century. Their application for a Ford Foundation grant to fund the seminar, hence the beginning of McLuhan’s career as a communications guru, may have started as a lark between them.

Perhaps incidentally, McLuhan offered this description of the prairie meadowlark in his conversation with Easterbrook in Speaking of Winnipeg:

We might as well have a few words about the superiority of the prairie meadowlark to all other songbirds (…) it has a much longer and almost melodic phrase. It isn’t a mere chirp; it has a melody. It talks to you. Besides it is extremely musical. It’s not just the solid glug-glug of the nightingale [championed by uninformed ornithologists like John Keats]. By comparison with the birds I’ve heard in Europe and England, it is enormously superior.

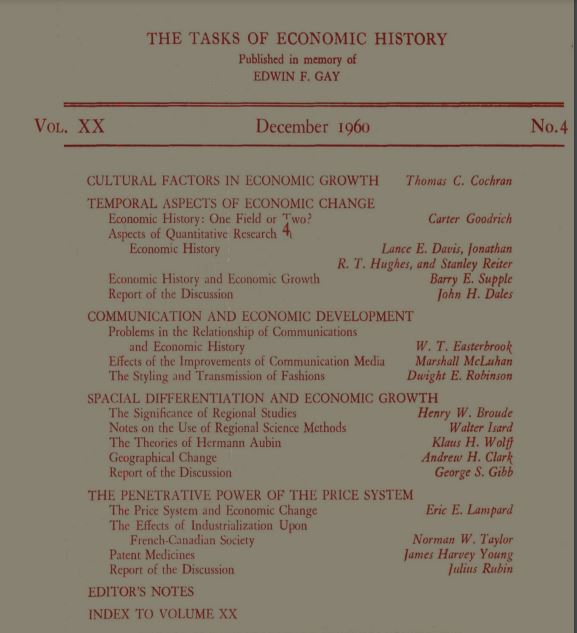

Like his friend and mentor, Harold Innis, Easterbrook went on to became chairman of the Political Economy department in Toronto. In 1960 he and McLuhan lectured together at the annual meeting of the Economic History Association. Innis had been one of its founders in 1940 and its second president in 1942.

After McLuhan’s death at the end of 1980, Easterbrook expressed his regret that their relationship had been so argumentative. But their gapped complementarity on everything doubtless benefited them both in multiple ways and served as the cement in their half century friendship.

- In his oral history Easterbrook recalled that they actually met the next year, 1930, after both had quit engineering for Economics (Easterbrook) and English (McLuhan). ↩

- Hayakawa lived with the Allisons (just down the street from the McLuhans) after his parents returned to Japan in the mid 1920s. ↩

- Elsie and Maurice McLuhan left Winnipeg for Toronto at the same time that Easterbrook did. He began grad studies at UT in the fall of 1933 and Elsie and Maurice decamped in September that year.

Elsie announced her departure with this press release. It appeared in the Winnipeg Evening Tribune for September 9, 1933, p4. ↩