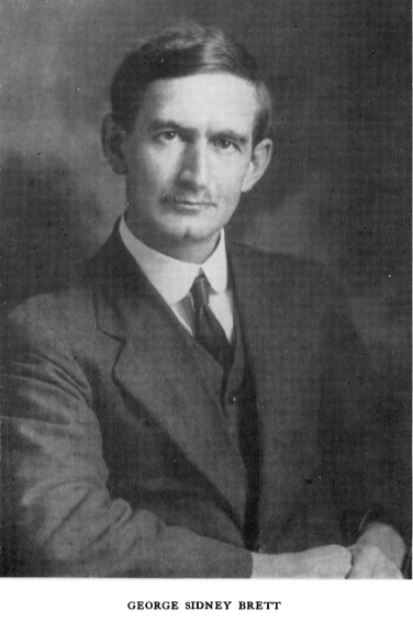

G.S. Brett (1879-1944), longtime University of Toronto professor and Harold Innis’ predecessor as Dean of Graduate Studies, had died by the time McLuhan got to Toronto in 1946. But Brett’s Psychology Ancient and Modern was familiar to McLuhan, perhaps through Carl Williams who knew of Brett’s work from his grad studies in psychology at UT in the 1930s.1

Additionally, McLuhan may have known Brett’s work from the 1922 Festschrift Philosophical Essays Presented to John Watson, in which his University of Manitoba mentors, Henry Wright and Rupert Lodge, were two of the eleven contributors. Two of the others were University of Toronto colleagues, Henry Carr and Brett.

Brett’s Psychology Ancient and Modern is cited in The Gutenberg Galaxy (p 74):

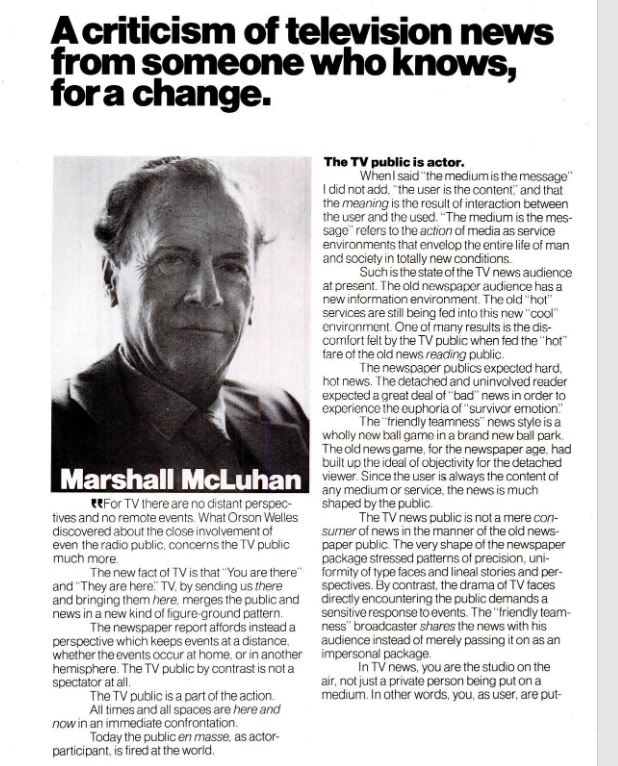

Only one third of the history of the book in the Western world has been typographic. It is not incongruous, therefore, to say as G.S. Brett does in Psychology Ancient and Modern:

The idea that knowledge is essentially book learning seems to be a very modern view, probably derived from the mediaeval distinctions between clerk and layman, with additional emphasis provided by the literary character of the rather fantastic humanism of the sixteenth century. The original and natural idea of knowledge is that of “cunning” or the possession of wits. Odysseus is the original type of thinker, a man of many ideas who could overcome the Cyclops and achieve a significant triumph of mind over matter. Knowledge is thus a capacity for overcoming the difficulties of life and achieving success in this world.2

Brett here specifies the natural dichotomy which the book brings into any society, in addition to the split within the individual of that society.

The image of the Cyclops appears frequently in McLuhan’s work, usually signifying unipolar ‘thinking’ that is lacking in depth perception (because lacking the bipolarity necessary for it).

A further passage in Brett concerning the “spontaneous act of the soul” reminds of McLuhan’s idea that the “power of detached observation” provides an escape from the media maelstrom.3

The mystics were always more or less Platonic; mediaeval Platonism handed on to modern times the one indispensable principle that every fragment of knowledge, though it may be conditioned by the sense, involves a spontaneous act of the soul. Platonism thus became the natural creed of all who believed that consciousness cannot be reduced to physiological terms.4

- Williams obtained his MA (1937) and PhD (1940) in psychology from UT. He took at least one seminar with E.A. Bott (see D.C. Williams, ‘Bott’s “Systematic” Seminar: Some Recollections‘, Canadian Psychologist / Psychologie canadienne, 15:3, 1974, 299–301), who would be credited with Williams’ ideas on ‘auditory space’ in the culture and technology seminar. Williams’ undergraduate degree came from the University of Manitoba, where he and McLuhan continued their high school friendship. At that time the University of Manitoba had not yet separated the Philosophy and Psychology departments. But William’s decision to take advanced degrees in psychology at UT must have been influenced by Henry Wright, who was the head of the psychology subsection within the Philosophy department at UM and would become the first head of the separated department of Psychology when it finally came into independent existence in 1945. ↩

- Psychology, Ancient and Modern, 36. ↩

- ‘Footprints in the Sands of Crime’ (1946): “The sailor in his (Poe’s) story The Maelstrom is at first paralyzed with horror. But in his very paralysis there is another fascination which emerges, a power of detached observation which becomes a “scientific” interest in the action of the strom. And this provides the means of escape.” ↩

- Psychology, Ancient and Modern, 150. ↩