We must make therefore a complete solution and separation of nature, not indeed by fire, but by the mind, which is a kind of divine fire. (Novum Organum, #41)

The doctrine of names is, of course, the doctrine of essence and not a naive notion of oral terminology. (The Classical Trivium, 16)

Just as language offers an extensive and complex apprehension of the structure of beings, so that faculty which produced this state of language is perpetually operative — an intuitive perception of essentials. There is no room for error in our intuitive grasp of nature, but in our methods of inference leading to the forming of opinions there is much likelihood of error. (The Classical Trivium, 51)

“…the entrance into the kingdom of man, founded on the sciences, being not much other than the entrance into the kingdom of heaven, where into none may enter except as a little child.” (‘Francis Bacon’s Patristic Inheritance’, 8, citing Bacon’s Novum Organum)

[Bacon cited] the widely held Christian tradition that Solomon alone of the sons of men had recovered that natural wisdom and metaphysical knowledge of the essences of things, of which Adam had been deprived. It is precisely to the task of recovering natural wisdom that Bacon’s labours were addressed. (‘Medieval Grammar as the Basis of Bacon’s Novum Organum‘, 168)

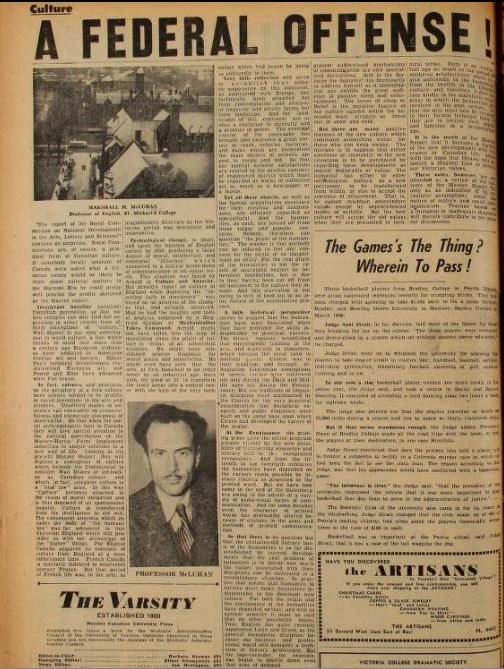

McLuhan noted in his Cambridge PhD thesis on Thomas Nashe that he had begun a monograph on Bacon, but had put it aside when a paper by Richard McKeon appeared that covered much the same ground:

I have already suggested how completely Bacon’s scientific program was tied up with grammar and dialectics and with rhetorical theory and practice, and had already undertaken a separate monograph on this subject before McKeon’s paper appeared. (The Classical Trivium, 119n22)

Parts of this effort which could have eventuated in a monograph on Bacon are be found in two posthumously published papers which go back to 1942-1943 when McLuhan was feverishly writing his thesis: ‘Francis Bacon’s Patristic Inheritance’ (“Expanded version of a paper written for the M.L.A. meeting of 1942″) and ‘Medieval Grammar as the Basis of Bacon’s Novum Organum‘ (dated by hand to February 22, 1943). These two papers must have had a complicated origin in relation to the Nashe thesis and to each other. Then (like the thesis itself) they were continually revised and mined for different purposes, not only in the 1940s, but throughout McLuhan’s lifetime (as late, eg, as ‘Francis Bacon: Ancient or Modern’ in 1974) — and even after his lifetime by Eric McLuhan. No effort will be made to retrace this complicated history here.

As broached in his Nashe thesis, McLuhan’s chief point in the ‘Patristic Inheritance’ paper was that Bacon was both the herald of the coming scientific age and the heir of ancient tradition:

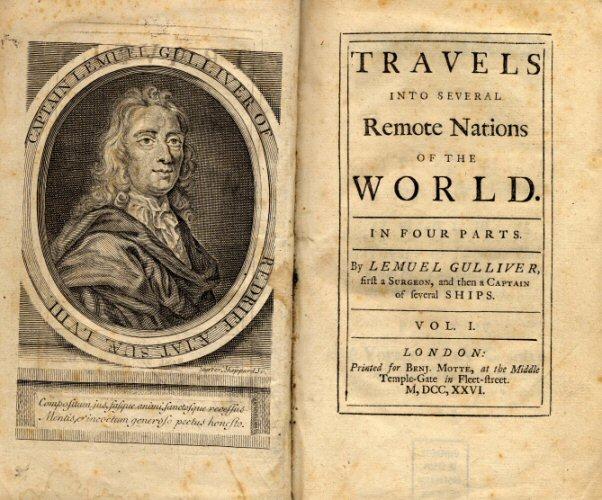

I shall try to show that [Bacon’s] concept of science and the way in which he stresses the arts of the trivium entitle him to be considered a highly orthodox ancient, a representative of a long and uninterrupted line of interpreters of the “book of nature”. (7)

If these — the revolutionary insights of modern science and the anchor of tradition — could be shown to be fundamentally linked, the incomparably important result would be to suggest, conceivably even to help demonstrate, that modern science does not contradict the tradition, but presupposes it and, properly understood, furthers it and affirms it.

This would, of course, be transformative. Instead of the tradition and science being two continents drifting inexorably apart in unrecallable divide, or, in reverse fashion, moving unstoppably into catastrophic collision, they would form a bulwark together against our reigning nihilism.

The role of language and its implicated grammar as the key to both spiritual and natural investigation was formulated in the Nashe thesis as follows:

From the time of the neo-Platonists and Augustine to Bonaventura and to Francis Bacon, the world was viewed as a book, the lost language of which was analogous to that of human speech. Thus the art of grammar provided the sixteenth-century approach not only to the Book of Life in scriptural exegesis but to the Book of Nature, as well. (The Classical Trivium, 7)

it was not only in antiquity but until the Cartesian revolution that language was viewed as simultaneously linking and harmonizing all the intellectual and physical functions of men and of the physical world as well. (The Classical Trivium, 16)

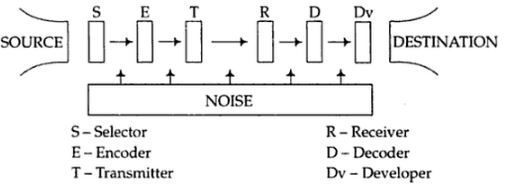

Now “human speech” takes place first of all through a curious chain of recognition: the recognition that certain environmental sounds are peculiar objects, namely words, the recognition that those words have certain restricted meanings, the recognition that those meanings may be controlled through certain manipulations (the province of traditional grammar). Fundamental to all of these is the prior (but unknown or at least ignored) recognition that humans exist in a communicative matrix in which, alone, something like a meaningful word, together with its enabling net of meanings and grammar, is possible at all.

Just as a newborn must learn to breathe in the new matrix of air after its life in the womb for nine months, so (during its life in in-fancy — ‘non-speaking’ — for a further 12 months or so) must it learn to function in that matrix of communication in which alone humans exercise their being.

As with its acclimatization to air, so in regard to the matrix of communication is it necessary for the infant to learn to live with what is already there and on no account to attempt to invent something of its own:

Just as the grammarian is always compelled to establish and stick to a text, so Bacon urges the scientist always to stay with nature and never to build hypotheses such as William Gilbert [1544-1603] did. Thus, the Novum Organum is a set of rules for interpreting and clarifying the obscurities of nature, but rules designed always to refer the observer back to his text [of word or world], and to prevent him both from “anticipations” and from contumacious construction, or hypotheses. (20)

Bacon viewed the rerum natura as a book, and man’s task as the true exegesis thereof: “For God forbid that we should give out a dream of our own imagination for a pattern of the world; rather may He graciously grant to us to write an apocalypse or true vision of the footsteps of the Creator imprinted on His creations.” The restoration of the study of languages is indispensable since grammar is as it were the harbinger of other sciences. (19-20)

Taken in this broad sense, grammar was the enabling matrix of “exegetical techniques of interpretation” (9), and this, in turn, fundamentally the effort to supply “the name which each thing by nature has”. The ancient tradition of grammar (gen. subj.), according to McLuhan, attended this exercise as the basic way in which humans exist.

These grammatical recognitions which infants must learn to perform are, of course, seldom considered. As McLuhan often remarked, the ubiquitous goes unperceived. Nor need they be perfect. Sounds may be mispronounced or misheard and yet still be understood. Meanings may be confused but usually with little ill effect. Grammatical mistakes may be made without necessary problems. Language is able to struggle through such imperfections because it is, so to say, more basic than they are.

The great mystery is: what is the source of such recognition? How does a child recognize that some sounds are words with meaning and other sounds are meaningless? Or that some meanings work for a word and others do not? Or that some manipulations are significant and others are not? And if this mystery is somewhat obscured when it is repeated by infants millions of times a day around the world, how did it take place in the first place?

McLuhan read Bacon as participating in a “grammatical” tradition for which such recognition was the chief characteristic of both theology and science and, in fact, of all history. Just as humans somehow sort words from noise, so (analogously) do they differentiate holy things from profane things and learn to sift out the elements in all sorts of scientific disciplines. Grammar may in this broad way be termed the study of the recognition of what things are and are not, whether these things be words or physical stuff or gods. It is the “harbinger” of study and reflection in all these areas since, like human speech itself, none can begin without sufficient recognition (conscious or unconscious) of the particular nature at stake in the activity at hand.

What an infant must first of all come to understand in learning to speak is that it exists in a universe where communication is a basic possibility. This understanding is of course only implicated in the infant’s growing capability to process and produce meaningful sounds, but it is the foundation of all that it does and all that it will ever do.

Socrates concurs in Cratylus’ statement that “a power more than human gave things their first names, and that the names which were thus given are necessarily their true names.” (10-11)

McLuhan enlarged on this point in his Nashe thesis as follows:

Plato’s Cratylus broaches the question of analogy and anomaly in such a way as to indicate that their dispute was of ancient origin even in his day, but the issues [between the two], of course, are drawn on a plane loftier than that of conjugations and declensions. Socrates refutes the superficial anomalist doctrine of Hermogenes at great length. Hermogenes says, ‘I have often talked over this matter, both with Cratylus and others, and cannot convince myself that there is any principle of correctness in names other than convention and agreement.’ Socrates replies that ‘I should say that this giving of names can be no such light matter as you fancy, or the work of light or chance persons; and Cratylus is right in saying that things have names by nature, and that not every man is an artificer of names; but he only who looks to the name which each thing by nature has, and is, will be able to express the ideal forms of things in letters and syllables.’ The general incredulity concerning Socrates’ seriousness in this dialogue is an adequate measure of the modern failure to apprehend the nature of grammar in the ancient and medieval worlds; and much of Plato’s power over St. Augustine and the medieval mind [generally] is owing to his great, though not exclusive, respect for the method of grammar in philosophy. It is quite impossible to make any sense of the scope and intensity of the strife between the analogists and anomalists unless the philosophic implications are perceived. (The Classical Trivium, 28)

The “first names” which were “true names” were not certain sounds (which of course vary between languages); instead the action at stake was the recognition of names as names, of words as words, of the fact that a certain kind of sound in the environment carries meaning.

The doctrine of names is, of course, the doctrine of essence and not a naive notion of oral terminology. (The Classical Trivium, 16)

The Stoics, of course, are analogists to a man, although Varro, himself, as well as Cicero, Caesar, Pliny, and Quintilian, freely admit the influence of custom or usage on language. (The Classical Trivium, 27)

By extension, this (usually utterly unattended) existence in a matrix of meaning enabling the recognition of essential natures happens again when a geometer understands a shape like a triangle as significant in a way a squiggle is not; or when copper is recognized as significant in a way wood is not. None of these recognitions begins (or ends) in perfection, but all do begin and apparently they do so through some “power more than human”. For we do not recognize through recognition (as the occultists maintained and as seems to be implied in much research into how infants learn to speak), but through a possibility built into the very nature of the universe that is there before us and that is deeper than us.

The initial imposition of names in this sense signifies essence, metaphysical knowledge. The corresponding doctrine, that to know the name of a thing was to have direct power over it, is responsible for what we have so long smiled at as alchemy. (11n14)

Bacon, like the Stoics, was an analogist, though a cautious one. That is, he held the ancient doctrine (…) of the Cratylus of Plato. An understanding of the great historical dispute waged for many centuries between the analogists and the anomalists is basic to an understanding of ancient, medieval, and Renaissance culture. (10n7)

The doctrine of the Logos, with its insistence of the dynamic unity of all nature, inevitably made for the encyclopedic ideal which we find equally in the practice of the Stoics, the Fathers, in Vincent of Beauvais, Roger Bacon, and Francis Bacon. Isidore of Seville named his encyclopedic synthesis of the arts Etymologiae simply because grammar (with etymology) was the basic mode of the synthesis. (12n16)

The fact that man was distinguished from the brutes by virtue of his power of speech was the fact which in connection with the doctrine of the Logos lent special impetus in the ancient world to the cultivation of eloquence. After Isocrates and Cicero, it was urged as a reason for the arduous disciplines of speech by the Fathers, by Alcuin, John of Salisbury, and humanists of the Renaissance. This is signally the case with Francis Bacon. From the humanist point of view, Socrates had initiated the fatal destruction of eloquence and good letters by his divorce between head and heart, thought and speech. It is impossible to exaggerate the importance of this insight for the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. This extraordinary account of the disastrous rise of Greek dialectics and the breach between eloquence and wisdom (the humanists of the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries make precisely the same complaints about the rise of [scholastic] dialectics in the twelfth century) is given classic statement in Cicero’s De Oratore. Francis Bacon repeats and endorses this account of Cicero’s. (10n10)

Bacon readily allows the validity of the physics of the Timaeus but points out that it is theological, concerned with final causes. This, of course, is the reason it was held in such esteem in the Middle Ages. Similarly, Aristotle’s physics is valid within its limits, but the method is dialectical and the aim no more for the relief of men’s estate than Plato’s. The trouble with Plato and Aristotle, said Bacon, is that they are more interested in truth than utility. (11n14)

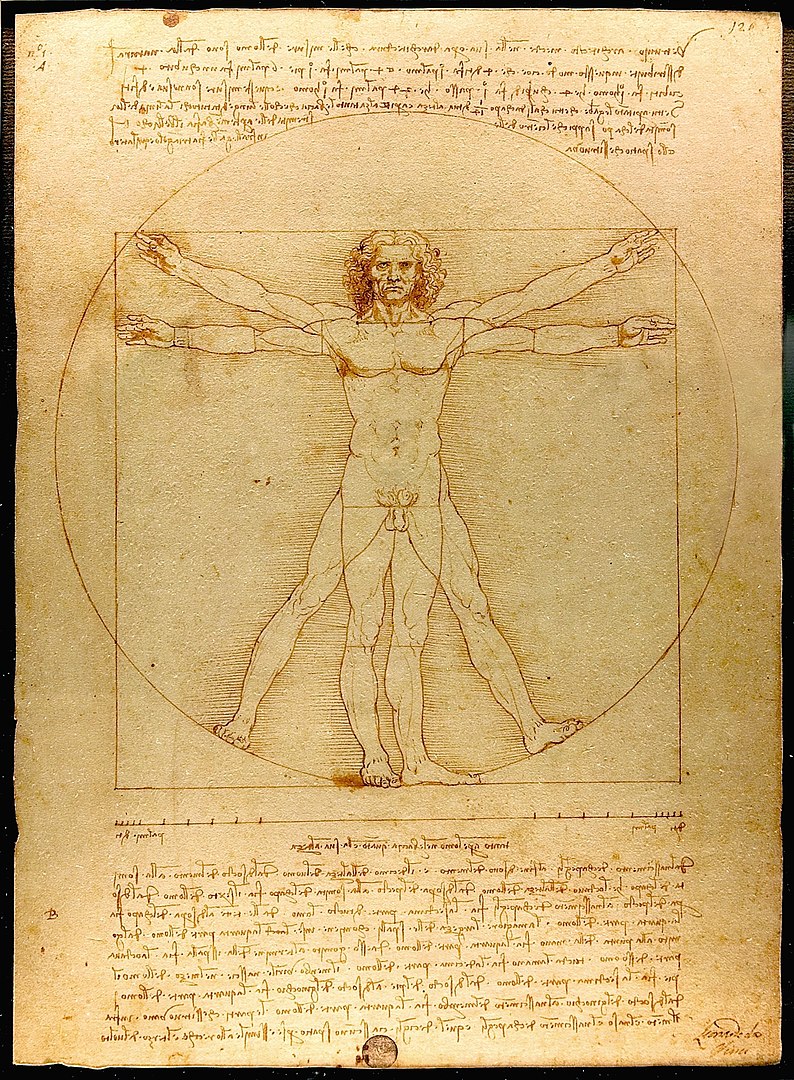

The kind of importance attaching to traditional grammar [in this much broader sense than we now understand] in Bacon’s scheme is evident from the following passage: “Concerning Speech and Words, the consideration of them hath produced the science of Grammar (…) examining the power and nature of words as they are the footsteps and prints of reason, which kind of analogy between words and reason (…) I think (…) very worthy to be reduced into a science by itself.” In this latter philosophical sense, grammar had been the main mode of physics, cosmogony, and theology for centuries [before Bacon, or even millennia]…(9)

This understanding of the imperative role of the recognition of natures in all human activity whatsoever and especially in the study of sacred and natural phenomena led Bacon to a novel view of history from Adam to himself and beyond into “a new period of study”:

Francis Bacon envisaged his encyclopedic task as the vindicator of ancient truths, which had been obscured by the arrogant follies (…) of Plato and Aristotle and (…) of the Schoolmen, and [also] as the “buccinator” [or herald] of a new period of study… (13)

Bacon wished to associate his endeavors with the widely held Christian tradition that Solomon alone of the sons of men had recovered that natural wisdom and metaphysical knowledge of essence of which Adam had been justly deprived. (8)

What kind of knowledge was lost by Adam in consequence of his fall? Fortunately it isn’t necessary to speculate about [Bacon’s] answer. (…) He states it thus in The Advancement of Learning: “After the creation was finished, it is set down unto us that man was placed in the garden to work therein; which work, so appointed to him, could be no other than the work of Contemplation. […] Again, the first acts which man performed in Paradise consisted of the two summary parts of knowledge; the view of creatures, and the imposition of names.” [Works VI, 137-138] The view upon creatures and the imposition of names corresponds precisely to the major aims of Bacon’s own program. The first was to be achieved by a universal natural history [as his field of inquiry], the second by exegetical techniques of interpretation [of that field] based on traditional grammar. (9)

Just as Adam had had the power to give the names (essences) to things, so Solomon in viewing creatures had written commentaries of precisely the kind which Bacon’s inductive method aimed to reproduce “touching the nature of things, wherein he treated of every vegetable, from the moss upon the wall to the cedar of Lebanon, and likewise of all animals…”. [Works IX, 239.] (9n4)

Typical of the statements by which Bacon focussed the scope and relevance of his work are the closing sentences of the Novum Organum: “For man by the fall fell at the same time from his state of innocency and from his dominion over creation. Both of these losses, however, can even in this life be in some part repaired: the former by religion and faith, the latter by arts and sciences. For creation was not by the curse [on Adam] made altogether and for ever a rebel, but in virtue of that charter ‘In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread’, it [creation] is now by various labours (…) at length and in some measure [to be] subdued (…) to the uses of human life.” [Works VIII, 350.] (7)