The stand should (…) have been taken (…) on plenary philology. That is, letters understood as the complete education in thought and feeling which fosters an integral humanitas. That is Viconian ground. The only fertile soil in the modern world. (McLuhan to John Palmer, November 4, 1946)

To [Vico] goes the credit for having maintained the autonomy of all the practical sciences of rhetoric, poetic, and history against the nullifying effects (so far as the practical intellectual arts are concerned) of mathematical speculation. (…) The (…) entirely relativist (…) bias of a contemporary sensibility (…) began perhaps with Vico’s sense of the simultaneous presence in men of the “three ages”. (McLuhan, Eliot’s Cubist Aesthetic, unpublished, c1947)

To get out of the wire cage (…) Vico provides both the techniques of observation and exegesis as well as the only method of escape. (McLuhan to John Palmer, December 9, 1949)

*

Vico: When man understands, he extends his mind and takes in the things, but when he does not understand, he (…) becomes them by transforming himself into them. (The New Science, §405, 1744)

McLuhan: Consider the effect of modern machinery in imposing rhythm on human thought and feeling. Archaic man got inside the thing that terrified him — tiger, bear, wolf — and made it his totem god. To-day we get inside the machine. It is inside us. We in it. Fusion. Oblivion. Safety. (McLuhan to Ezra Pound, January 1951, Letters p219)

*

Giambattista Vico is an example of a linguistic analogist in the eighteenth century (…) he held that all language was basically expressive of universal concepts. Says Croce: “Vico also looked forward to a universal system of etymology, a dictionary of mental words common to all nations.” (McLuhan, Francis Bacon’s Patristic Inheritance, 1944)

At the moment I’m reading Vico… (McLuhan to Cleanth Brooks, October 8, 1946)

Incidentally, the suggestion about intellectual self-portraits came to me from reading Vico’s autobiography. With him the problem of intellectual growth had been imposed by the struggle to free himself from Descartes. To-day, the problem is the same. To get free of technological modes which have invaded every aspect of education, of thought and feeling. (McLuhan to John Palmer, November 4, 1946)

the metaphor of simple linear perspective (…) yields in Vico to a complex genetic metaphor that becomes the intellectual means of being simultaneously present in all periods of the past and all mental climates of the modern world as well. (McLuhan, Inside Blake and Hollywood, 1947)

That great positivist synthesis [in Britain] lasted until the time of Herbert Spencer and petered out in the popular fantasies of the encyclopedic H.G. Wells. Meantime it was increasingly challenged by the more speculative synthesis which stemmed from Vico and Hegel and was carried on through Marx on the economic side and through Nietzsche on the psychological and philological fronts. However, it has never been understood that the second-rate character of the English and American nineteenth century as compared with the German and French was owing to the German and French having adopted psychological rather than the biological experience as the source of the guiding analogies for (…) social study and discussion. Adam Smith introduced into the intellectual currency the analogy of a vague evolutionary providence operating through both human and animal appetites. This analogy fructified the minds of Malthus and Darwin. But it was analogy quite incapable of stimulating the great anthropological and cultural histories which, under Viconian and Hegelian inspiration, appeared on the continent. Sir James Frazer and Arnold Toynbee are by-products of Max Muller and Oswald Spengler rather than of their own traditions.

Every age has its reigning analogy in terms of which it orients itself with respect to the past and directs its energies through the present to the future. To be contemporary in the good sense is to be aware of this [reigning] analogy. To be “ahead of the time” is to be critically aware of the [reigning] analogy. That is, to be aware that it is only one analogy. To be creative and directive of the currents of the age is, while admitting the limitations of the dominant analogy, to carry out as complete as extension and synthesis of the arts and sciences as it will permit. But also to explore as much new terrain in each art and science as it will allow. To recover as much of the past as can be made creatively relevant to the present. To be aware of the past as presently useful and of much of the present as already irrelevant — this is to be a contemporary mind. And this mode of awareness is itself based on an analogy derived from relativity physics (…) whose usefulness to a society faced with the problems of world government and international community is as immense as it is as yet unexploited. (McLuhan’s Proposal to Robert Hutchins, 1947)

To [Vico] goes the credit for having maintained the autonomy of all the practical sciences of rhetoric, poetic, and history against the nullifying effects (so far as the practical intellectual arts are concerned) of mathematical speculation. (…) Jung’s idea of the collective unconscious presents, like Vico’s, a similar multiplicity of simultaneous perspectives which has the effect (…) of conferring the sense of permanent and perpetual availability of the entire past in the present. (…) The (…) entirely relativist and Whiteheadian (…) bias of a contemporary sensibility (…) began perhaps with Vico’s sense of the simultaneous presence in men of the “three ages”. (McLuhan, Eliot’s Cubist Aesthetic, unpublished, c1947)

Vico’s great discovery of a psychological method for interpreting historical periods and cultural patterns is rooted in his perception that the condition of man is never the same but his nature is unchanging. (…) Vico (…) invented an instrument of historical and cultural analysis of the utmost use for the discovery of psychological and moral unity in the practical order… (McLuhan, Where Chesterton Comes In, 1948)

Finnegan as civilization hero. Purger of the crap of the tribe. Hercules and the Augean Stables. Diverted a river. Hence one reason for river importance in Finnegan. Hook up with Euripides’ Alcestis. Drunken Hercules descends to underworld. River of unconscious purging via puns. Puns technique of dislocation, irrigation, interpenetration of all levels of society and experience. All heading for bright sea of intelligibility. Hercules in this sense right out of Vico. (McLuhan to Cleanth Brooks, October 16, 1948)

Once Mallarmé had detached poetic act and knowledge from that rhetorical activity in which the poet quarrelled with his age, poetic knowledge was free to enter into the most intimate analogical relations with all phases of social consciousness and processes. A Viconian revolution in which a seeming impoverishment led to the final enrichment. (McLuhan, American Criticism and the Demons of Analogy, unpublished, c1948)

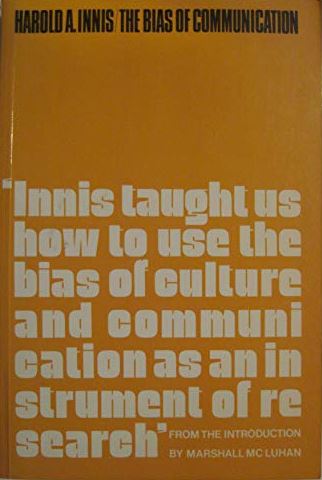

One major discovery of the symbolists which had the greatest importance for subsequent investigation was their notion of the learning process as a labyrinth of the senses and faculties whose retracing provided the key to all arts and sciences (basis of myth of Daedalus, basic for the dreams and schemes of Francis Bacon, and, when transferred by Vico to philology and history of culture (…) forms the basis of modern historiography, archaeology, psychology and artistic procedures alike). (McLuhan to Harold Innis, March 14, 1951, Letters p221)

Often noted from Montaigne onward is the growing interest in the anatomy of states of mind which in Giambattista Vico reached the point of stress on the importance of reconstructing by vivisection the inner history of one’s own mind. A century separates Vico’s Autobiography and Wordsworth’s Prelude, but they are products of the same impulse. Another century, and Joyce’s Portrait carries the same enterprise a stage further. Vico generalized the process as a means of reconstructing the stages of human culture by the vivisection and contemplation of language itself. (McLuhan, The Aesthetic Moment in Landscape Poetry, 1951)

At the time when Joyce was studying the trivium with the Jesuits there had occurred in the European world a rebirth of interest in the traditional arts of communication. Indirectly, this had come about through the reconstruction of past cultures as carried on by nineteenth-century archaeology and anthropology. For these new studies had directed attention to the role of language and writing in the formation of societies and the transmission of culture. And the total or gestalt approach natural in the study of primitive cultures had favored the study of language as part of the entire cultural network. Language was seen as inseparable from the tool-making and economic life of these peoples. It was not studied in abstraction from the practical concerns of society.

It was at this time that Vico came into his own. At the beginning of the eighteenth century Vico’s Scienza Nuova had proposed language as the basis for anthropology and a new science of history. Extant languages, he argued, could be regarded as working models of all past culture, because language affords an unbroken line of communication with the totality of the human past. The modalities of grammar, etymology and word-formation could be made to yield a complete account of the economic, social and spiritual adventures of mankind. If geology could reconstruct the story of the earth from the inert strata of rock and clay, the scienza nuova could do much better with the living languages of men. (McLuhan, James Joyce: Trivial and Quadrivial, 1953)

James Joyce certainly thought he had found in Vico a philosopher who had some better cultural awareness than those moved by the “Cartesian spring.” And Vico, like Heidegger, is a philologist among philosophers. His time theory of “ricorsi” has been interpreted by lineal minds to imply “recurrence.” A recent study of him brushes this notion aside. Vico conceives the time-structure of history as “not linear, but contrapuntal. It must be traced along a number of lines of development”. For Vico all history is contemporary or simultaneous, a fact given, Joyce would add, by virtue of language itself, the simultaneous storehouse of all experience. And in Vico, the concept of recurrence cannot “be admitted at the level of the course of the nations through time”: “The establishment of providence establishes universal history, the total presence of the human spirit to itself in idea. In this principle, the supreme ‘ricorso’ is achieved by the human spirit in idea, and it possesses itself, past, present, and future, in an act which is wholly consonant with its own historicity.” (McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy, 1962, p249-250)

Vico was the first to spot language itself as a memory theatre. Finnegans Wake is such a memory theatre for the entire contents of human consciousness and unconsciousness. With the arrival of the printed word, the whole fabric of these theatres collapsed quickly. The medieval cathedrals were memory theatres. The Golden Bough is a memory theatre of the corporate rather than the private consciousness and marks a major transition toward the retribalizing of human consciousness. (McLuhan to William Jovanovich, December 1, 1966, Letters p339)

James Joyce put the matter very simply in Finnegans Wake (81:1): “As for the viability of vicinals, when invisible they are invincible.” By “vicinals” Joyce alludes to Vico whose Scienza Nuova asserts the principle of the sensory and perceptual change resulting from new technologies throughout human history. Hence the ancients attributed god-like status to all inventors since they alter human perception and self-awareness. (McLuhan to Jacques Maritain, May 6, 1969, Letters p369-370)

There seems to be a general unwillingness to consider the impact of technological innovation on the human sensibility. The reason that Joyce considered Vico’s new science so important for his own linguistic probes, was that Vico was the first to point out that a total history of human culture and sensibility is embedded in the changing structural forms of language. (McLuhan to Robert J. Leuver, July 30, 1969, Letters p384-385)

Like Isadore of Seville, Vico saw the history of cultural evolution in the etymologies of words as recording responses to technological innovations. (McLuhan, From Cliché to Archetype, 1970, p127)

The Etymologiae of Isidore of Seville in the sixth century a.d. was a compendium of the arts and sciences. Etymology was understood to include the secret principles of all forms of being, physical and spiritual. In the seventeenth century Vico’s Scienza Nuova reasserted those ancient principles of verbal resonance as comprising the keys to all scientific and humanist mysteries. James Joyce, who incorporated not only Vico, but all the ancient traditions of language as science, alludes to the principal feature of this kind of “new science” in Finnegans Wake: “As for the viability of vicinals, when invisible they’re invincible.” The allusion to Vico is environmental (vicus: Latin for neighborhood), indicating the irresistible operation of causes in the new environments issuing from new technologies. Since these environments are always invisible, merely because they are environments, their transforming powers are never heeded in time to be moderated or controlled. (McLuhan, Take Today, 1972, p150-151)

In 1725 Giambattista Vico explained in his Scienza Nuova (§331): “But in the night of thick darkness enveloping the earliest antiquity. so remote from ourselves, there shines the eternal and never-failing light of a truth beyond all question, that the world of civil society has certainly been made by men, and that its principles are therefore to be found within the modifications of our own human mind.” (McLuhan, Laws of Media, posthumous, 1988, p4)

Vico (…) begins by reiterating and updating Bacon’s [four] Idols as his own first four Axioms. The first four axioms constitute the basis of Vico’s elements and, says Vico, “give us the basis for refuting all opinions hitherto held about the principles of humanity” (New Science, §163). “These four axioms express a theory of ignorance which we need in order to acquire a doctrine of truth concerning the nature of humanity.” (Laws of Media, p11)

The ‘myth of objectivity’, a result of visual bias, belongs to the ‘Idols of the Theatre’ or what Giambattista Vico termed ‘the conceit of scholars’ in his fourth axiom. Vico was merely following [Bacon’s] instructions when, at the outset of his Scienza Nuova, he set out his [four] ‘elements’ or ‘axioms’, for Bacon had prefaced his account of his [four] ‘Idols’ with these words: “The formation of ideas and axioms by true induction is no doubt the proper remedy to be applied for the keeping off and clearing away of idols. To point them out, however, is of great use for the doctrine of idols is to the interpretation of nature what the doctrine of the refutation of sophisms is to common logic.” (Laws of Media, p83-84)

Summing his great chapter on Poetic Wisdom. Vico reiterates: “We have shown that poetic wisdom justly deserves two great and sovereign tributes. The one, clearly and constantly accorded to it, is that of having founded gentile mankind, though the conceit of the nations on the one hand, and that of the scholars on the other, the former with ideas of an empty magnificence and the latter with ideas of an impertinent philosophical wisdom, have in effect denied it this honour by their very efforts to affirm it. The other, concerning which a vulgar tradition has come down to us, is that the wisdom of the ancients made its wise men, by a single aspiration, equally great as philosophers, lawmakers, captains, historians, orators and poets, on which account it has been so greatly sought after.” (Laws of Media, p85)

Western Old Science approaches the study of media in terms of linear, sequential transportation of data as detached figures (content); the New Science approach is via the ground of users and of environmental media effects. (Laws of Media, p85)

When determining the principles on which his Scienza Nuova would rest, Giambattista Vico, the last great pre-electric grammarian, decided to use cultures themselves as his text: “We must reckon as if there were no books in the world.” In shunning conventional science and returning to direct observation of the page of Nature, Vico pursued the same course Francis Bacon had charted in the Novum Organum... (Laws of Media, p215)

Vico’s technique is set forth in the second of his five books as the practical heuristic application of not philosophical but poetic wisdom. For method: “We must therefore go back with the philologians and fetch it from the stones of Deucalion and Pyrrha, from the rocks of Amphion, from the men who sprang from the furrows of Cadmus or the hard oak of Vergil.” Vico’s Science went one essential step beyond Bacon’s. Meditating on the relations between the two books, he found a new correspondence, an interplay that raised a new ‘text’ for grammatical scrutiny. “But in the night of thick darkness enveloping the earliest antiquity, so remote from ourselves, there shines the eternal and never-failing light of a truth beyond all question: that the world of civil society has certainly been made by men, and that its principles are therefore to be found within the modifications of our own human mind. Whoever reflects on this cannot but marvel that the philosophers should have bent all their energies to the study of the world of nature, which, since God made it, He alone knows, and that they should have neglected the study of the world of nations or civil world, which, since men made it, men could hope to know. This aberration was a consequence of that infirmity of the human mind, noted in the Axioms, by which, immersed and buried in the body, it naturally inclines to take notice of bodily things, and finds the effort to attend to itself too laborious; just as the bodily eye sees all objects outside itself but needs a mirror to see itself.” The new text is man’s social artefacts… (Laws of Media, p220-221)

Vico brings to bear all of the resources of grammar, both as regards exegesis of the two books and as regards the processes of etymology: “The human mind is naturally inclined by the senses to see itself externally in the body, and only with great difficulty does it come to attend to itself by means of reflection. This axiom gives us the universal principle of etymology in all languages: words are carried over from bodies and from the properties of bodies to express the things of the mind and spirit“. (Laws of Media, p221)

This passage puts on display the standard grammatical awareness of the correspondence of words and things, though seldom has it been made so explicit. As poetic (rhetorical) wisdom focuses on the sensibilities as crucial, Vico asserts that there must exist a mental dictionary, not of abstract philosophical ideas, but of concrete poetic-philological sensibilities conformal to the things and artefacts of common experience: “There must, in the nature of human things be a mental language common to all nations, which uniformly grasps the substance of things feasible in human social life, and expresses it with as many diverse modifications as these same things may have diverse aspects. A proof of this is afforded by proverbs or maxims of vulgar wisdom, in which substantially the same meanings find as many diverse expressions as there are nations ancient and modern. This common mental language is proper to our Science, by whose light linguistic scholars will be enabled to construct a mental vocabulary common to all the various articulate languages living and dead (…) As far as our small erudition will permit, we shall make use of this vocabulary in all the matters we discuss.“ (Laws of Media, p221-222)

Concluding his discussion of poetic wisdom, Vico accorded it ‘two great and sovereign tributes’. One is ‘that of having founded gentile mankind’; the other concerned the ‘wisdom of the ancients’ as sketched in the fables: “And it may be said that in the fables the nations have in a rough way and in the language of the human senses, described the beginnings of this world of sciences, which the specialized studies of scholars have since clarified for us by reasoning and generalization. From this we may conclude what we set out to show in this (second) book: that the theological poets were the sense and the philosophers the intellect of human wisdom.” (Laws of Media, p222)

Vico aimed to heal the rift in the trivium between the Ancients and the Moderns. He sought to avoid the faults that had accumulated in both philology and philosophy, since they were split in the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, by blending them: “Philosophy contemplates reason, whence comes knowledge of the true; philology observes the authority of human choice, whence comes consciousness of the certain. This axiom by its second part defines as philologians all the grammarians, historians, critics, who have occupied themselves with the study of the languages and deeds of peoples both their domestic affairs, such as customs and laws, and their external affairs, such as wars, peaces, alliances, travels and commerce. This same axiom shows how the philosophers failed by half in not giving certainty to their reasonings by appeal to the authority of the philologians, and likewise how the latter failed by half in not taking care to give their authority the sanction of truth by appeal to the reasoning of the philosophers. If they had both done this they would have been more useful to their commonwealths and they would have anticipated us in conceiving this Science.” (Laws of Media, p222-223)

Vico’s contemporaries were no more able to carry forward his work than were their successors, and so the problem has remained to this day (…) In the end, it eluded him for he was caught in a dilemma that had been building for centuries before him and that was then [invisible because] environmental. (…) Vico simply had not distinguished between first and second nature for separate study: nothing in his experience suggested such a distinction would be of any use. Second nature is nature made and remade by man as man remakes himself with his extensions. Separate them: the first is the province of traditional grammar; the second, that of Bacon, Vico, and Laws of Media. (Laws of Media, p223)

The key to Vico’s science was the mental dictionary (…) the dictionary of real words (…) is, as he anticipated, a ‘mental’ dictionary in that it displays patterns and transformations of sensibility. (Laws of Media, p223)

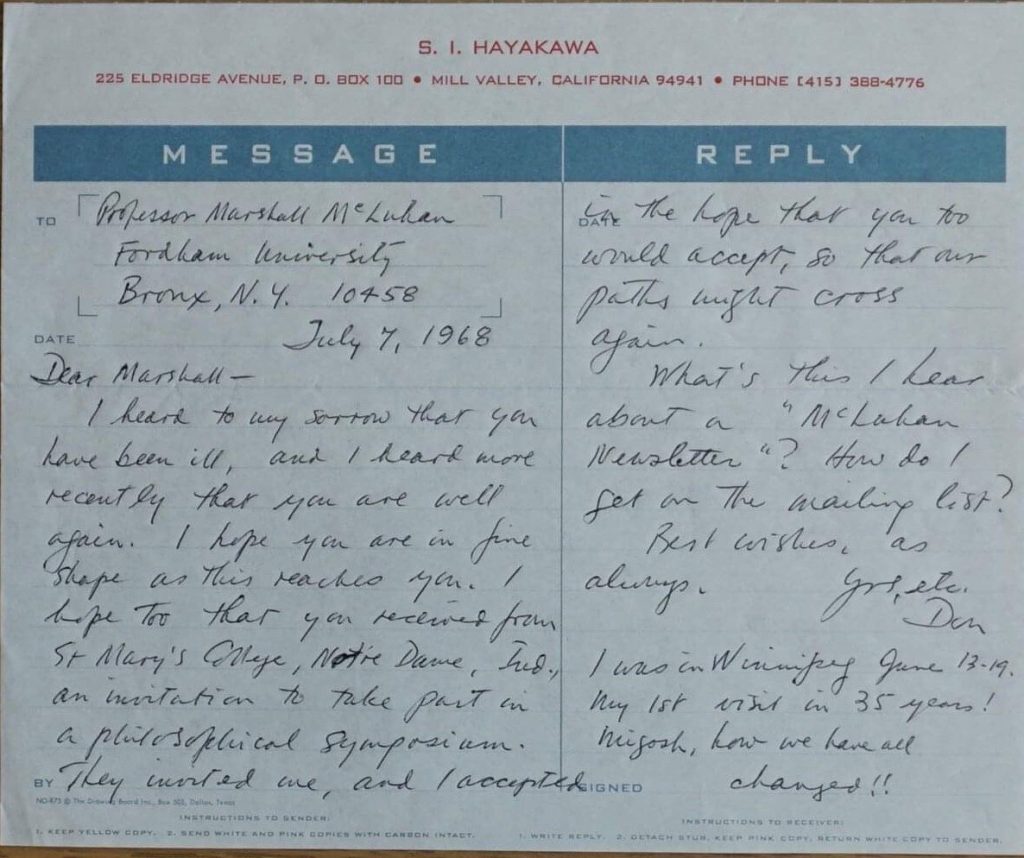

July 7, 1968

July 7, 1968